Thaxted

| Thaxted | |

|---|---|

Thaxted Windmill and Church | |

Location within Essex | |

| Population | 3,116 [1] |

| OS grid reference | TL615315 |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | DUNMOW |

| Postcode district | CM6 |

| Dialling code | 01371 |

| Police | Essex |

| Fire | Essex |

| Ambulance | East of England |

| UK Parliament | |

Thaxted is a town and civil parish in the Uttlesford district of north-west Essex, England. The town is in the valley of the River Chelmer, not far from its source in the nearby village of Debden, and is 97 metres (318 feet) above sea level (where the parish church stands).[2]

The town is 15 miles (24 km) north from the county town of Chelmsford and 5.5 miles (9 km) east from the M11 motorway. The parish contains the hamlets of Cutlers Green, Bardfield End Green, Sibleys Green, Monk Street and Richmond's Green. Much of its status as a "town" rests on its prominent late medieval guildhall, a place where guilds of skilled tradesmen regulated their trading practices, and its English Perpendicular parish church.

History

[edit]According to A Dictionary of British Place Names, Thaxted derives from the Old English thoec or þæc combined with stede, being a "place where thatching materials are got".[3] In the 1086 Domesday Book, the settlement is referred to as 'Tachesteda' and in subsequent official records variously as "Thacstede",[4] "Thaxstede", "Thackestede" and "Thakstede",[5] amongst other spellings.[6] As late as the nineteenth century, the spelling "Thackstead" was still in use.

Thaxted developed as a Saxon settlement on a Roman road.[7] There was a Roman villa to the east of the current town[8] and Roman artefacts have been discovered in the area.[9] The British Museum holds a Roman bronze head of Bacchus found at Thaxted in the nineteenth century.[10] The first documented record of Thaxted, including a church, is in the Liber Eliensis, describes a gift of land in "Thacstede" by a woman named Æthelgifu at some time between 881 and 1016.[4]

Archeological research of the area by Oxford Archaeology in 2007 produced finds showing Bronze Age, late Iron Age, Roman, late medieval and post-medieval occupation, including flint fragments, floor and roof tiles, pottery sherds, ditch enclosures, graves, and skeletal remains.[9] A further archeological excavation in the centre of the town by the Colchester Archeological Trust in 2015 found a large medieval ditch which may have been a part of the town's defences, 15th- to 16th-century artifacts, and fragments of animal bone waste, mainly from cattle.[11]

In the 1086 Domesday Book, the settlement, in the Hundred of Dunmow, consisted of 108 households with a population of 54 villagers, 34 smallholders, 16 slaves, and 4 freemen. The land supported 28.5 plough teams—being seven lord's teams and 21.5 men's teams—and contained two mills, meadow of 154 acres (0.62 km2), and woodland with 850 pigs. In 1066 there were four cobs, 36 cattle, an additional 128 pigs, 200 sheep, and 10 beehives. The sheep had increased to 320, and the beehives to 16, by 1086. In 1066 the lord was Wihtgar, son of Aelfric, who was lord or overlord of 27 other manors, chiefly in west Essex. After 1086 the lordship of Thaxted was given in part to Warner, and to Richard fitz Gilbert—son to Gilbert, Count of Brionne—who was also Tenant-in-chief to the king.[12]

During the Middle Ages, Thaxted prospered as a centre for the production of cutlery. This association is recalled by the town's well-known guildhall, by the town badge which consists of two crossed swords, and in the name of the nearby hamlet of Cutlers Green.[13] Why a town like Thaxted, lacking in the natural resources required for the large-scale manufacturing metal products, should have developed this industry is unclear.[14] Although it had been assumed that Thaxted's cutlers were finishing blades made elsewhere, excavations undertaken in 2015 in Orange Street found evidence to support the work of bladesmiths alongside cutlers/hafters.[15][16]

The cutlers seem to have been already well-established by the beginning of the fourteenth century: in 1310, a cutler named Adam de Thakstede had prospered enough to purchase the freedom of the City of London and set up business in Cheapside.[17] A manuscript in the Bodleian Library indicates that Thaxted was already widely identified with its cutlery by the 1320s.[18][19] The 1381 Poll Tax returns indicate 79 cutlers established in Thaxted, alongside other related trades such as smiths and sheathers.[14]

This artisanal development had an effect on the economic and social dynamics of the town, shifting from a feudal agricultural model, in which most people were dependent on and laboured for the lord of the manor, to an urban industrial model where many people were employed and more autonomous.[20] The right to hold a market was granted in 1205.[21] Sometime during the first half of the fourteenth century, certain town inhabitants acquired the status of burgesses (burgenses) living within an area of the town known as the borough (burgus), achieving some degree of freedom from obligations toward the manor.[20][22]

However, this independence "did not extend to any real measure of self-government".[20] The exact date that Thaxted first acquired formal borough status is unknown but the 1556 charter states that Thaxted "is an ancient borough and had from time immemorial a mayor and other officers and ministers and was endowed with diverse liberties".[23] Royal documents from the end of the fifteenth century refer to the "manor and borough of Thaxted".[24] It seems clear however that Thaxted did not achieve self-government as a fully-fledged borough until the granting of the 1556 charter.[25]

A guild of cutlers was established during the reign of Edward III (1327–77), led by a warden.[26] In November 1481, Edward IV, at the behest of his mother, Cecily, who held the manor, issued letters patent to license some residents of Thaxted "to found a fraternity or perpetual gild", empowered to regulate itself and own land.[27] A deed of foundation of the "fraternity or perpetual guild of St. John the Baptist at Thaxted" dates from 1507.[28] The famous Guildhall is supposed to have been built by the cutlers' guild. However, it seems there was, at one time, more than one guild in existence in the town – and more than one guild hall: there is some evidence for a guild or fraternity dedicated to the Holy Rood,[29] and the Ordnance Survey map of 1876 shows the site of a guild hall in Vicarage Mead, off Newbiggen Street.[30] An historical account of the town in 1831 states that the "mote hall" [the extant guildhall] was being used as a school and the "guild hall" was the town workhouse.[31]

In 1556, the town took advantage of the fact that the lord of the manor was a minor to request incorporation of the borough, which was granted by Philip and Mary, allowing a town government consisting of a mayor, two bailiffs, twenty-four burgesses, a court, a recorder and two serjeants at law, amongst other officers. The Charter describes the borough as having fallen into "great ruin and decay by reason of great poverty and necessity"; the charter may have signalled an effort to revitalise the fortunes of the town and was reconfirmed by Elizabeth I and James I.[32] However, despite efforts to encourage the development of the wool trade in the town with the creation of a guild of clothiers in 1583, Thaxted's fortunes did not return. The charter was extinguished in 1686 after the town was unable to challenge a quo warranto writ by James II.[32]

Governance

[edit]Thaxted Parish Council consists of 11 elected members who each serve a term of 4 years.[33] The parish council is responsible for managing certain amenities and open spaces, including the Recreation Ground and Sports Pavilion, the Windmill, Bolford Street Hall, the allotments, the public car parks in Park Street and Margaret Street, the public toilets, Margaret Street Gardens and the green space at Cutlers Green.

Thaxted lies within the Thaxted and the Eastons Ward for Uttlesford District Council which elects two representatives to serve on the district council. Thaxted lies within the Thaxted Division (or super ward) for Essex County Council, which also covers the surrounding villages of Ashdon, Debden, Little Dunmow, the Eastons, Felsted, Hempstead, the Sampfords, Stebbing and Wimbish, and elects one county councillor.

The Thaxted electoral ward had a recorded population of 5,291 at the 2021 census.[34]

Thaxted acquired borough status sometime in the fifteenth century.[24] It was incorporated by charter in 1556 as a borough and "body corporate and politic", governed by a common council of twenty-four "capital burgesses" including an elected mayor, and seated at the Guildhall[23] The borough status lapsed in 1686,[35] but Thaxted continues to be referred to as a "town" by its inhabitants.

Demography

[edit]In 1829, there were 2,293 people living in Thaxted; in 1848 there were 2,527. At the time of the 1881 census, that figure had fallen to 1,914, and it fell further by 1921 to 1,596.

In 2001, the population had risen again to 2,526. The 2011 census put the total population of Thaxted at 2,845.[36] By the 2021 census, the figure had risen to 3,116 inhabitants.[1]

Education

[edit]Thaxted County Primary School was established in 1878 under the 1870 Education Act.[29] It still occupies the fine Victorian building on the eastern edge of the town built for it in 1880 and is run by Essex County Council.

Thaxted lies within the secondary education catchment area for the Helena Romanes School in Great Dunmow.

There are a number of preschools in the area.[37]

The 1556 Borough Charter provided for setting up a grammar school.[23] This occupied the Guildhall from 1714 until it closed in 1878. A day school, operated by the Church of England, opened in 1819 and was housed in a building funded by Lord Maynard on the Broxted Road. The non-conformists established a rival British School in Bolford Street in 1856. Both schools ceased to operate when the Primary School was established in 1878.[29]

From 1944 to 1962, the Bachad Farm Institute, located on a farm at Bardfield End Green, provided agricultural training to young Jewish refugees, including many from the Kindertransport, as part of a network of hakhshara youth training farms.[38][39]

Amenities

[edit]Thaxted Public Library is operated by Essex County Council and located in Town Street.[40] A Community and Tourist Information Office is located within the Library, staffed by volunteers.[41]

There are a number of venues for meetings in the town. The Guildhall is sometimes used for events, meetings and exhibitions.[42] Bolford Street Hall, formerly the British School built in 1849, is maintained by the parish council.[43] Thaxted Church Hall in Margaret Street in maintained by the Thaxted Church Hall Trust together with the parish church.[44]

Thaxted Parish Council maintains public parks and open spaces, including the Margaret Street Garden, the Recreation Ground and Sports Pavilion, Walnut Tree Meadow in Copthall Lane, and the greens at Cutlers Green and Bardfield End Green.[45] The latter is the location of the cricket ground. There are numerous public footpaths offering walks and hiking opportunities; the Harcamlow Way long-distance trail passes through the town.[46]

Thaxted Surgery, situated in Margaret Street, provides general practice healthcare to the community.[47] The Thaxted Centre for the Disabled, founded in 1963 and situated on Dunmow Road, supports persons with physical disabilities through volunteers and community fundraising.[48]

Essex County Fire and Rescue Service maintains an on-call fire station in Thaxted, with locally based firefighters on standby to respond to incidents.[49]

Culture and community

[edit]

Between 2007 and 2009, a village design statement was produced for Thaxted to describe the character of the town and parish and to inform any future development. It was drawn up after consultation with local residents and under the auspices of Thaxted Parish Council and the Thaxted Society, and was published after further consultation with the rural community council and Uttlesford District Council.[50]

The Thaxted Society is a conservation charity founded in 1963 to safeguard and promote Thaxted's legacy.[51] It publishes the Thaxted Bulletin twice a year, with the 100th edition appearing in winter 2017. The society's remit is to scrutinise and respond to local planning and Government planning regulation and policy.[52]

The annual Thaxted Festival takes place over four weekends in June and July every year,[53] presenting a programme of musical concerts.[54]

Thaxted Cricket Club represents the town and parish. The club's teams play in the Herts & Essex Border League, play Sunday Friendlies, and in under-12 and under-15 competitions.[55]

Thaxted's football club, Thaxted Rangers, was formed in 1998 and has a senior team and youth teams.[56]

Thaxted Bowling Club was founded in 1965 and has a green and clubhouse off Park Street.[57]

Thaxted Tennis Club operates from tennis courts situated on Dunmow Road at the southern entrance to the town.[58]

Thaxted Morris Men is a morris side, which was founded in 1911 under the instigation of Conrad Noel, Vicar of Thaxted, as a response to a renewed interest in morris dancing. The side (team) performed locally as part of coronation celebrations for George V.[59]

Since 2001, Thaxted has been twinned with Saint-Vrain in the French department of Essonne. A twinning association aims to promote friendship and cultural understanding and to foster the relationship between the two towns and their people.[60]

According to a local vicar, in local Essex dialect the word "thaxted" meant "sharp, clever" – an apparent reference to the former cutlery industry.[61]

Transport

[edit]

Thaxted once lay on the busy A130 trunk road from Chelmsford to Cambridge which brought large trucks through the centre of the town past the Guildhall and Church. In the 1980s, this route was downgraded to become the B184 road[62] following completion of the M11 motorway and the A120 dual carriageway. Ordnance Survey maps show a Roman road running north to south through Thaxted.[63]

Thaxted is connected to the local towns and villages, as well as to Stansted Airport, by local bus services, operated by Stephensons of Essex. Uttlesford District Council runs a community travel service for residents who have difficulty using public transport.[64]

From 1913 to 1952, Thaxted was served by a light railway branch line from Elsenham which ran to a terminus station located about one mile south of the town. The line, the Elsenham & Thaxted Light Railway, was known to locals as the "Gin and Toffee" line because the main investors where a local sweet factory owner and a distillery magnate.[65] Passenger traffic ceased on 15 September 1952 and the line closed definitively on 1 June 1953.

Between 1916 and 1919, Thaxted hosted a Home Defence aircraft landing ground. The unit was equipped with Royal Aircraft Factory BE2 and BE12 variants fighters of No. 75 Squadron until the summer of 1918, and thereafter with Avro 504Ks and Bristol F2bs. The site was decommissioned at the end of the First World War in 1919. The landing ground was located north of Bardfield End Green.[66]

Landmarks and notable buildings

[edit]

Thaxted Parish Church is a fine example of English Perpendicular church architecture built between 1340 and 1510 and a testament to the prosperity of the town in the Middle Ages. It is one of the largest churches in Essex, 183 feet long and 87 feet wide with a spire reaching 181 feet and is dedicated to St John the Baptist with Our Lady and St Laurence.[67]

Thaxted Guildhall is a Grade I listed timber-framed medieval moot hall in the main high street.[68] It was built in the late 15th century, supposedly with funding from the significant cutlery industry, hence the assumption that it served the cutlers' guild.

John Webb's Windmill is a restored brick tower mill, built in 1810, standing to the south of the church. The view of the windmill from the Bullring, framed by the almshouses, is a classic Essex postcard view. The Almshouses consist of the thatched Chantry House[69] and the tiled Almshouses building[70] of 1714, the latter still in use providing accommodation for elderly people.[71]

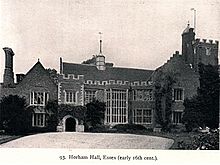

Horham Hall is a Grade I listed mansion to the south-east of the town of Thaxted.[72][73] It was built in brick by Sir John Cutte between 1510 and 1515, on the site of a timber-framed late–c. 1470 moated manor house.

Clarence House is a Grade I listed Queen Anne townhouse in Watling Street, opposite the church. It was built in 1715 and retains many original features.[74] Its garden wall is Grade I listed separately.[75]

Dick Turpin's Cottage is one of a group of timber-framed terrace houses in picturesque Stoney Lane, but there is no evidence to support its association with the famous highwayman.[76] It, along with Nos. 2 and 4 either side, are Grade I listed buildings.[77]

On the south side of Town Street, the former Recorder's House – named because it was once the home of the first Recorder under the 1556 Charter, Serjeant Bendlowes – has carvings beneath the windows including the arms of Edward IV.[78] It is Grade II* listed.[79]

Thaxted and music

[edit]

In the twentieth century, Thaxted developed a musical tradition that can be traced back to the influence of the composer, Gustav Holst, and Conrad Noel, the vicar of Thaxted.[80]

In 1913, while on a walking holiday, Holst discovered the town and remained associated with it for the rest of his life. Encouraged by the vicar, Conrad Noel, a medievalist and folk-dancing and church music enthusiast, Holst had the idea of organizing a Whitsun festival there, bringing singers and players from St Paul's Girls' School and Morley College in London to join with local people in a weekend of musical festivities. In 1916, once he had finished The Planets, he devoted time to writing and arranging music especially for Thaxted. The carols Bring us in good ale (dedicated to Conrad Noel), Lullay my liking, Of one that is so fair and bright and Terly, terlow were specifically written for Thaxted. His most outstanding achievement was This have I done for my true love (also dedicated to Noel), "an evocation of the medieval notion of dancing and religious worship being closely intertwined".[81] Holst's daughter, Imogen Holst, a composer in her own right, also maintained links with the town.

Although the Whitsun Festival was discontinued in 1918, the idea was revived in 1980 and flourishes as the Thaxted Festival.

Thaxted is the name given to a hymn tune, a setting for "I Vow to Thee, My Country", which Holst composed, based on the theme of "Jupiter" in his orchestral Planets suite.[7] Holst wrote the Planets whilst living in a cottage in Monks Street outside Thaxted.

Thaxted and Morris dancing

[edit]The Thaxted Morris Men were formed in 1911[82] as part of the Morris dancing revival underway in the first half of the twentieth century. The Thaxted Morris is now the oldest revival side in the country.

During the Great War, many active Morris men were killed, and the Morris was predominantly women. By the 1930s, men predominated again. In 1934, the year that Holst died, the Cambridge Morris Men invited five other teams (Letchworth, Thaxted, East Surrey, Greensleeves and Oxford) to join them in the formation of a national organisation. Five of the six teams met at Thaxted on 11 May 1934 to inaugurate The Morris Ring.

The Ring, which has grown to around 180 sides, organises regular meetings. The annual Thaxted Morris Weekend, which takes place on the Spring Bank Holiday weekend, welcomes sides from all over the United Kingdom and the world. The weekend consists of a series of dancing tours, in which teams dance in the villages surrounding Thaxted, before reconvening in the town. The final dance of the evening is always the evocative Abbots Bromley Horn Dance, performed by the host side from Thaxted, winding their way from the churchyard, down Stoney Lane and past the Guildhall, accompanied by a solitary fiddler. The Morris Weekend is a major tourist attraction pulling visitors to the town each year.[83]

Thaxted in film

[edit]The town and surrounding countryside feature in the documentary film Ripe Earth, directed and produced by the Boulting Brothers in 1938.[84] The ten-minute film depicts the gathering of the harvest in Rails Farm and the harvest festival celebration in the church, including Conrad Noel at the altar.

The town was used as the location for the 1952 British comedy film Time Gentlemen, Please![85] The film was directed by Lewis Gilbert, starred Eddie Byrne, and also featured Dora Bryan and Sid James.

Part of Passolini's The Canterbury Tales (I racconti di Canterbury) was filmed in Thaxted: the unrestored Windmill, with the church spire in the distance, formed the backdrop to the scene depicting the Summoner, the Devil and the Old Woman in The Friar's Tale, somewhat anachronistically since the tower mill is a nineteenth century structure of the Industrial Revolution that would have been unknown in Chaucerian times.

Notable people

[edit]

- Robert Wydow or Wedow (c. 1446 – 1505), an English poet, church musician, and religious figure, was born in Thaxted and was vicar of the town from 1481 to 1489. He attended Eton College and King's College Cambridge, and is the first known recipient of a Bachelor of Music degree in England, awarded by Oxford University in 1478 or 1479. Wydow's contemporaries held him in high esteem as a poet and musician, describing him as "an excellent poet", and "easily the finest" of Latin authors of the time. However, only a few lines of his poetry survive and none of his music. The surviving brass in the Parish Church is reputed to be his likeness. Wedow Road, in the town, commemorates him.

- Sir John Cutte (d. 1520), Under-Treasurer to Henry VII and Henry VIII, built Horham Hall on the site of an earlier house.[86] His grandson, Sir John Cutte (1545-1615), hosted Queen Elizabeth I in 1571 (nine days) and 1578 (six days).[87]

- Sir John Alleyn or Allen (c.1470-1544), mercer in the City of London, was born in Thaxted.[88] He served two terms as Lord Mayor of London, in 1525 and 1535.[89] His immediate predecessor as Lord Mayor, Sir William Bailey, serving in 1524, was also from Thaxted.[90]

- Samuel Purchas (1577–1626), English cleric and author, was born in the town. His works are an important source of information about the age of exploration.[91] He graduated from St John's College, Cambridge, in 1600.[92] His most famous work, Hakluytus Posthumus, or Purchas his Pilgrimes, Contayning a History of the World, in Sea Voyages, & Lande Travels, by Englishmen and others (1625) is a massive compilation of accounts by Elizabethan and Jacobean travellers of their journeys around the world. Yet he noted with some irony that "I, which have written so much of travellers and travels, never travelled 200 miles from Thaxted in Essex where I was borne".[93]

- Dick Turpin (1705–39), the famous highwayman, was born in nearby Hempstead and was reputed to have run a butcher's shop in Thaxted.[94] Contemporary biographies claiming that he was born in Thaxted are erroneous; and there is no evidence to support a connection with the cottage in Stoney Lane that carries his name.[citation needed]

Samuel Purchas never travelled further than 200 miles from Thaxted, the town of his birth, yet became famous for his works on global travel from the age of Discovery. He was a contemporary of Shakespeare. - John Fell (1733–97), Classical scholar and author, lived in Thaxted from 1770 as minister of the Congregationalist chapel. He was friends with Rayner Heckford, a Saxon scholar, whose family owned Clarence House. Whilst in Thaxted, he tutored the young Richard "Conversation" Sharp (1759-1835), who went on to become a famous wit, literary figure and a Member of Parliament.[95]

- Alfred Paget Humphry (1850-1916), barrister, is buried in Thaxted. He bought Horham Hall in 1905 and lived there until his death. He was a renowned champion rifle shooter and wrote First Hints at Rifle Shooting (1876).[86]

- Conrad Noel (1869–1942), Christian socialist, was known as the town's 'Red Vicar', serving in the post from 1910 until his death.[96] He played a key role in the morris dancing revival in the town. He enjoyed the patronage of Daisy, Countess of Warwick, of Easton Lodge.

- Launcelot Alfred Cramner-Byng (1872-1945), sinologist and author, lived at Folly Mill, near Monk Street. He translated many works of Chinese literature.

- Gustav Holst (1874-1934), the British composer of The Planets, lived in The Manse (then called The Steps) in the High Street. His residency is marked by a blue plaque.[97] His daughter, Imogen Holst, also lived in the town in her youth.

- Alec Butler Hunter (1899-1958), textile designer, lived at Market Cross, a fine medieval house next to the Guildhall, from 1944 until his death.[98] He worked for Warner & Sons, the textile manufacturer in nearby Braintree, and was a President of the Society of Industrial Artists.[99] He was an active supporter of Morris dancing revival and the first Squire of the Morris Ring.[83] The Alec Hunter Academy in Braintree is named after him.

- Sir George Binney (1900– 72), Arctic explorer, lived at Horham Hall from 1946 to 1969.

- W. E. Shewell-Cooper (1900–82), gardener and pioneer of organic gardening, lived and worked at Prior's Hall, outside the town, from 1948 to 1960, where he ran a training college promoting organic horticulture.[100]

- Alan Rawsthorne (1904-1971), English composer, and his wife Isabel Rawsthorne (née Nicholas) (1912-1992), English painter and scenery designer, are both buried in Thaxted churchyard. They lived in a cottage in the neighbouring village of Little Sampford.

- Isabel Alexander (1910-1996), artist and illustrator, lived in Thaxted between 1949-1964 while working at Saffron Walden Teacher Training College.[101] Some of her works depict Thaxted and the surrounding landscape.[102][103][104]

- Donald Hall (1928-2018), American poet and writer, spent a year in Thaxted between 1959 and 1960, during which time he wrote his collection of poems, A Roof of Tiger Lilies, and his short story collection, A String Too Short To Be Saved.[105] His poem, An American in an Essex Village, describes a walk around the town at that time, including the church and the then derelict windmill whose "ruin appals only an eye which invents a landscape which needs it."[106]

- Evelyn Anthony (Evelyn Bridgett Patricia Ward-Thomas) (1926-2018), novelist, lived at Horham Hall from 1968 to 1976 and again from 1982 to her death.[107] Her most successful novel was The Tamarind Seed, which was made into a feature film.

- Diana Wynne Jones, author of Howl's Moving Castle and other novels, was raised in the town.[108]

- Genista McIntosh, Baroness McIntosh of Hudnall, the Labour life peer, lived in Thaxted from 2002 to 2015.[109] She spoke in praise of Thaxted Parish Church in a debate in the House of Lords in 2014.[110]

Places of worship

[edit]

The Church of Saint John the Baptist with Our Lady and Saint Laurence, the Church of England parish church, is a large English Perpendicular style medieval church which commands the town from the hilltop. The church was, in the twentieth century, the centre of so-called "Thaxted Movement", which combined High Church Anglo-Catholicism with Christian Socialism. The benefice has since 2017 been joined to the neighbouring parishes of Hempstead, Radwinter and the Sampfords.[67]

In the eighteenth century, Thaxted became a centre for non-conformity when an independent meeting house was established. This became a Congregationalist Chapel at which the minister was John Fell. The United Reformed Church, in Bolford Street, was built in 1876 on the site of the earlier Congregationalist chapel.[29] The Baptist Church, in Park Street, occupies a Georgian building dating from 1832.[111] There was once also a Quaker meeting house at Mill End: the building was later incorporated into the sweet factory and still exists.[112] The Exclusive Brethren established a meeting house in the Tanyard in the 1940s.

In 1942, a Roman Catholic Church, dedicated to the English Martyrs, was built in Park Street. With the building recently condemned, the congregation are currently making use of the Lady Chapel in the Anglican parish church.[113]

Industry and commerce

[edit]The prosperity of Thaxted was once built on the cutlery and wool trades but by the seventeenth century these had wained. By the nineteenth century, Thaxted was a depressed agricultural backwater. In 1870, George Lee opened a sweet factory in the town, which rapidly became the major employer.[29] It saved Thaxted, became a major employer and led to the advent the light railway, with the support of the gin magnate, Sir Walter Gilbey. Because the railway was promoted by a gin distiller and a confectioner, it was known by the locals as "The Gin and Toffee Line".[65][114] The sweet factory closed in 1969 and its site, at the eastern entrance to the town, was used by a tea packing company and, from 1976 to 2013, by a pharmaceutical company.[115] It has since been redeveloped for residential use.[116]

Cedric Arnold, a pipe organ maker, had a workshop at Mill End for many years.[117][29] He built one of the organs in the parish church.[118] The business was eventually subsumed by Messrs. Hill, Norman & Beard Ltd. and relocated away from Thaxted. Another light industry that came and went was the wiremaker, Cowell & Cooper, which opened in 1946 but moved to Haverhill in 2009.[119]

Agriculture remains an important part of the local economy.[29]

The town maintains a modest selection of shops, including a supermarket, a post office, a long-established hardware shop and a bakery, as well as a petrol station. When Thaxted was a borough, it acquired the right to hold a weekly market on Fridays.[23] Although this lapsed, the market was revived in the 1990s and continues to be held most Fridays in Town Street. Since 2008, the market has been administered by the Parish Office.

Thaxted once possessed a copious number of public houses, but many have been lost.[120] The Fox and Hounds on the northern entrance of the town is now a care home. The Bull in Newbiggen Street has become a private house, as has The Cock Inn in Watling Street. The Saracen's Head stood on the site now occupied by Saracen's Filling Station in the southern entrance to the town. Lowe's hardware shop in Town Street was once The Duke's Head, a coaching inn. Bell Lane gets its name from The Bell, which occupied the house on the corner with Watling Street that was subsequently the post office and is now an Indian restaurant. The Butchers Arms at Bardfield End Green, which once sustained the cricket club, has also closed.

Three public houses remain in the town itself: the Swan Hotel, opposite the Church, is an historic coaching inn in a Grade II listed building;[121] the Star, in Mill End, occupies a Grade II listed hall house from the fourteenth century;[122] The Maypole, formerly the Rose & Crown, is at the top of Mill End opposite the petrol station. Outside the town is the Farmhouse Inn, formerly the Greyhound, a fifteenth-century hall house in the hamlet of Monk Street, on the road to Dunmow.

Gallery

[edit]-

Parish church of St John

-

The Guildhall and Stoney Lane, leading to the Parish Church

-

The Guildhall, Thaxted

-

Nave, Thaxted Parish Church, Essex

-

Almshouses at the church, with the sailless John Webb's Windmill in the background

-

The Manse where composer Gustav Holst lived from 1917 to 1925

-

Dick Turpin's cottage, suggesting the supposed association of the highwayman with Thaxted

-

John Webb's Windmill

-

Thaxted Windmill

-

Thaxted Church and Windmill, from the south

-

Watling Street, Thaxted

-

Houses in Watling Street, including Clarence House.

-

The Recorder's House in Town Street, Thaxted

-

Thelwall Morrismen at the Thaxted Ring Meeting

-

Houses in Watling Street, opposite the north porch of the Parish Church, Thaxted

-

Cottage in Thaxted, opposite the north porch of the Parish Church

-

Town sign in Thaxted, Essex

-

Post Office in Thaxted, Essex

-

The Manse, former home of Gustav Holst in Town Street, Thaxted

-

Samuel Purchas, writer, born in Thaxted

-

Conrad Noel, Vicar of Thaxted from 1910 to 1942

-

The Borough, farm on the outskirts of Thaxted and a reminder of the town's former status as a borough and centre of industry

-

The centre of Thaxted has changed little since 1961

-

Park Farm House, Park Street, Thaxted

-

Thaxted from the Dunmow road to the south

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Thaxted (Essex, East of England, United Kingdom) - Population Statistics, Charts, Map, Location, Weather and Web Information".

- ^ The Guildhall stands about 8 metres lower than the churchyard and the river another ten metres lower still. "Elevation Finder". freemaptools.com. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Mills, Anthony David (2003); A Dictionary of British Place Names, Oxford University Press, revised edition (2011), p.455. ISBN 019960908X

- ^ a b Thomas of Ely, fl 1174; Richard of Ely, d 1194? supposed author (1848). Liber Eliensis, ad fidem codicum variorum. Londini, Impensis Societatis. p. 176.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ See for example the entries in the various Calendars of Patent Rolls published by the Public Record Office.

- ^ "Thaxted :: Survey of English Place-Names". epns.nottingham.ac.uk. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Thaxted – Tilty, Essex", The Guardian, 2 June 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2018

- ^ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments and Construction of England (1916). An inventory of the historical monuments in Essex: 74: Thaxted. London: H. M. Stationery Office. p. 302.

- ^ a b Stansbie, D.; Brady, K.; Biddulph, E.; Norton, A.; "A Roman cemetery at Sampford Road, Thaxted, Essex", Archeological Publication Report (January 2008), Oxford Archaeology. Retrieved 1 August 2018

- ^ "statuette | British Museum". The British Museum. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ "Fascinating medieval finds from historic Thaxted", The Colchester Archeologist, 19 March 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2018

- ^ Thaxted in the Domesday Book. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ^ "Cutlers Green :: Survey of English Place-Names". epns.nottingham.ac.uk. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ a b Newton, Kenneth Charles (1960). Thaxted in the Fourteenth Century: An Account of the Manor and Borough, with Translated Texts. Essex County Council. p. 21.

- ^ Pooley, Laura. "Archaeological evaluation and excavation on land to the north of Orange Street, Thaxted, Essex, CM6 2LH: January and April-May 2015" (PDF). cat.essex.ac.uk. Colchester Archaeological Trust. p. 35. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ In the Middle Ages, the term "cutlery" did not refer to tableware, as it does today, but to the manufacture of blades, knives and swords. The manufacturing process involved the work of a blademith (who forged the metal blade), a hafter (who made the handle from wood or bone) and a cutler (who finished the sharpened and polished blade with its handle).

- ^ Welch, Charles (1916). History of the Cutlers' Company of London and of the minor cutlery crafts, with biographical notices of early London cutlers; Volume 1. London. p. 71.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Cotels de Thaxsted" in MS. Douce 98, ff.195-6, Bodleian Library

- ^ Bonnier, C. (1901). "List of English Towns in the Fourteenth Century". The English Historical Review. 16 (63): 501–503. doi:10.1093/ehr/XVI.LXIII.501. ISSN 0013-8266. JSTOR 549210.

- ^ a b c Newton, Kenneth Charles (1960). Thaxted in the Fourteenth Century: An Account of the Manor and Borough, with Translated Texts. Essex County Council. p. 22.

- ^ "Heritage Gateway – Essex Historic Environment Record No. 1397". heritagegateway.org.uk. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- ^ The farm, and the bridge over the Chelmer, at the bottom of Bolford Street still carry the name "The Borough" to this day.

- ^ a b c d Public Record Office. "Calendar of the patent rolls, preserved in the Public Record Office; Volume 3 (1555-1557)". HathiTrust. p. 154. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ a b Benham, W. Gurney (1916). Essex Borough arms and the traditional arms of Essex and the arms of Chelmsford diocese. Colchester: Benham & Co. pp. 48–51. hdl:2027/uc1.b2794001.

- ^ Newton, Kenneth Charles (1960). Thaxted in the Fourteenth Century: An Account of the Manor and Borough, with Translated Texts. Essex County Council. p. 23.

- ^ Symmonds, George E. "Thaxted and its Cutlers Guild" (PDF). Proceedings of the Essex Archeological Society. III (New Series): 255–61.

- ^ Public Record Office. "Calendar of the Patent Rolls (1476-1485)". HathiTrust. p. 227. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ Essex County Council. "Deed of foundation of the franternity or perpetual guild of St. John the Baptist at Thaxted, by John Hasilwode of Thacted, only survivor of those granted licence (letters Patent) by Edward IV, at the instance of his mother Cecily, duchess of York, 4 Dec. 1480. Essex Archives Online – Catalogue: D/DSh/Q1". essexarchivesonline.co.uk. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Arman, Mark (1983). An historical guide and brief tour of the Ancient Town of Thaxted in Essex. Thaxted. ISBN 0946943001.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "OS Six-inch England and Wales, 1842-1952". National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ^ Wright, Thomas; Bartlett, W. (1831). The history and topography of the county of Essex, comprising its ancient and modern history. A general view of its physical character, productions, agricultural condition, statistics &c. &c. London: Geo. Virtue. p. 242.

- ^ a b Steer, Francis (1951). Thaxted in Essex: A short guide to the buildings of historical and architectural interest. Thaxted Festival of Britain Committee. pp. 2–3.

- ^ "Thaxted". www.thaxted.co.uk. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ "Thaxted & the Eastons". censusdata.uk. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ "The Guildhall". thaxted.co.uk. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ Thaxted Neighbourhood Plan 2017-2033 (PDF). Uttlesford District Council. 2019. p. 11.

- ^ "Education". thaxted.co.uk. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ Steele, Verity (1 September 2017). Ploughing a Furrow to Zion: Fostering Ideals and Identities through the Agricultural Training of European Jewish Youth – A Case Study of the Bachad Movement 1928-1962 (masters thesis). University of London.

- ^ "HOME". Verity Steele. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ^ "Thaxted Library". libraries.essex.gov.uk. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ "Information Centre & Library". thaxted.co.uk. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ "The Guildhall". thaxted.co.uk. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ "Bolford Street Hall". Thaxted Parish Council. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ "Thaxted Church Hall". thaxtedchurchhall.co.uk. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ "Open Spaces". thaxted.co.uk. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ "Harcamlow Way – Long Distance Walkers Association". ldwa.org.uk. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ "Thaxted Surgery". Thaxted Surgery. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ^ "The Thaxted Centre For The Disabled". Trumpet.co.uk. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ^ "Thaxted Fire Station". Essex County Fire & Rescue Service. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ^ Thaxted Design Statement. Retrieved 1 August 2018

- ^ "What we do". The Thaxted Society. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ^ "Thaxted Society Constitution" (PDF). Thaxted Society. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ "A timeless musical experience". Thaxted Festival. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ^ Ward, Amy (September 2008). "A Centre for Culture". Essex Life. Archant: 94. Retrieved 24 January 2009.

- ^ Thaxted Cricket Club. Retrieved 2 August 2018

- ^ "Thaxted Rangers". Trumpet.co.uk. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ^ "Thaxted Bowling Club – Club History". thaxtedbowlsclub.co.uk. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ^ "Thaxted Tennis Club". Thaxted Tennis Club. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ^ Thaxted Morris Men. Retrieved 2 August 2018

- ^ "Thaxted Twinning Association". Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ Gepp, Edward (1920). A contribution to an Essex dialect dictionary. London: G. Routledge. p. 36.

- ^ "B184". Sabre. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ^ "Map of Braintree & Saffron Walden". Ordnance Survey Limited. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ "Uttlesford Community Travel – Helping Residents Get Around". Uttlesford Community Travel. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ a b Oppitz, Leslie (1989). East Anglia Railways Remembered. Newbury: Countryside. p. 105. ISBN 1-85306-040-2. OCLC 20800104.

- ^ "Thaxted – Airfields of Britain Conservation Trust UK". abct.org.uk. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ a b "The Churches of Thaxted, The Sampfords, Radwinter and Hempstead". ttsrh.org. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ "GUILDHALL, Thaxted – 1112905 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ "THE CHANTRY, Thaxted – 1322220 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ "ALMSHOUSES, Thaxted – 1165533 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ "Almshouses". thaxted.co.uk. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ "HORHAM HALL, Thaxted – 1165290 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ "HORHAM HALL, Thaxted – 1322572 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ "CLARENCE HOUSE, Thaxted – 1166193 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ "GARDEN WALL TO CLARENCE HOUSE FRONTING BELL LANE AND MARGARET STREET, Thaxted – 1322228 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ "Thaxted – Short History of Thaxted". thaxted.co.uk. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ "3, STONEY LANE, Thaxted – 1112934 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ Steer, Francis (1951). Thaxted in Essex: A short account of the buildings of historical and architectural interest. Thaxted Festival of Britain Committee. p. 4.

- ^ "RECORDER'S HOUSE, Thaxted – 1112902 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ Holst, Imogen (1995). Gustav Holst and Thaxted: A Short Account of the Composer's Association with the Town of Thaxted Between 1913 and 1925. Thaxted: Mark Arman. ISBN 0946943109.

- ^ "Holst: This have I done for my true love & other choral works". Hyperion Records. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ "History of Thaxted Morris". Thaxted Morris Men. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ^ a b Read, Julian (3 June 2014). "A Thaxted tradition". Essex Life Magazine. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ "Ripe Earth 1938, Thaxted (Essex)". University of East Anglia: East Anglian Film Archive. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ^ "Time Gentlemen Please". Reel Streets. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ a b Munro, Bruce. "Some Stately Homes of North-west Essex" (PDF). Saffron Walden Historical Journal. 14, 15 & 17.

- ^ "The Elizabethan Court Day by Day – Folgerpedia". folgerpedia.folger.edu. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ "Allen, Sir John (c. 1470–1544), mayor of London". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/68011. Retrieved 11 November 2020. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Addenda: The Mayors and Sheriffs of London | British History Online". british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Orridge, B. B. (1867). Some Account of the Citizens of London and Their Rulers, from 1060 to 1867. London: Tegg. p. 226.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 659.

- ^ "Purchas, Samuel (PRCS594S)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ Purchas, Samuel (1625). Hakluytus posthumus, or Purchas his pilgrimes : contayning a history of the world in sea voyages and lande travells by Englishmen and others; Volume I. 1905 edition printed by Glasgow University Press. Glasgow: J. Maclehose. p. 201.

- ^ Barlow, Derek (1973). Dick Turpin and the Gregory Gang. London: Phillimore. p. 8. ISBN 0-900592-64-8. OCLC 798125.

- ^ Simcoe, Ethel (1934). A Short History of the Parish and Ancient Borough of Thaxted. Saffron Walden: Hart. p. 117.

- ^ "Conrad Noel". Henry S. Salt Archive. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ^ "Gustav Holst". thaxted.co.uk. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ "'Birthplace' of Morris revival comes onto the market". mullucks.co.uk. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- ^ "Alec Butler Hunter". Journal of the Textile Institute Proceedings. 49 (2): P84. 1 February 1958. doi:10.1080/19447015808688328. ISSN 1944-7019.

- ^ Conford, Philip (Summer 2009). "Gardeners and Growers" (PDF). The Organic Grower: Journal of the Organic Growers Alliance (9): 24.

- ^ Alex, Robin; er (22 November 2022). "Isabel Alexander: Artist and Illustrator". Wales Arts Review. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ "Now representing: Isabel Alexander". www.bridgemanimages.com. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ "Results for". www.bridgemanimages.com. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ "Isabel Alexander: Artist and Illustrator". Parthian Books. Retrieved 5 August 2024.

- ^ Hall, Donald; Hamilton, David (1985). "An Interview with Donald Hall". The Iowa Review. 15 (1): 1–17. doi:10.17077/0021-065X.3148. ISSN 0021-065X. JSTOR 20156112.

- ^ Hall, Donald (1962). "An American in an Essex Village". The Hudson Review. 15 (2): 235–237. doi:10.2307/3848544. ISSN 0018-702X. JSTOR 3848544.

- ^ Kean, Danuta (10 October 2018). "Evelyn Anthony obituary". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ Butler, Charlie (31 March 2011). "Diana Wynne Jones: Doyenne of fantasy writers whose books for children paved the way for JK Rowling". The Independent. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ^ Friends of Thaxted Church. "Friend's News: 2019". fotc. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ "My Lords, I shall speak briefly in...: 12 Jun 2014: House of Lords debates". TheyWorkForYou. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ "BAPTIST CHAPEL, Thaxted – 1322232 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ "MP UNITED DRUG COMPANY (BUILDING ADJOINING TO SOUTH EAST OF PREVIOUS ITEM AND FRONTING ROAD), Thaxted – 1112946 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ "Holy Spirit Great Bardfield & English Martyrs, Thaxted : Homepage". bardfieldandthaxted.org.uk. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ Crosby, Tony (2010). THE THAXTED BRANCH LINE SURVEY: An Archaeological Assessment of the Former Elsenham – Thaxted Light Railway (PDF). Essex Industrial Archaeology Group (EIAG) Reports. Essex Society for Archaeology and History (ESAH). p. 5.

- ^ "Our history". Molecular Products. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ "The Old Sweet Factory". Mole Architects. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ "Biographical Dictionary of the Organ | Cedric Arnold". organ-biography.info. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ "The Churches of Thaxted, The Sampfords, Radwinter and Hempstead". ttsrh.org. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ "Cowell and Cooper". cowellandcooper.co.uk. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ "Lost Pubs in Thaxted, Essex". closedpubs.co.uk. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ "The Swan Hotel | Thaxted | Official Website". greenekinginns.co.uk. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ "The Star | Thaxted | The Star Inn Thaxted". Mysite. Retrieved 1 November 2020.