Female Trouble

| Female Trouble | |

|---|---|

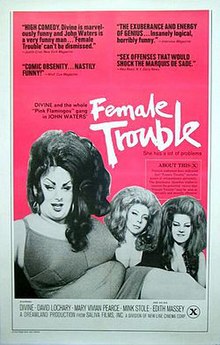

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Waters |

| Written by | John Waters |

| Produced by | John Waters |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | John Waters |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by |

|

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | New Line Cinema |

Release date |

|

Running time |

|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $25,000 |

Female Trouble is a 1974 American independent[1] dark comedy film written, produced and directed by John Waters. It stars Divine, David Lochary, Mary Vivian Pearce, Mink Stole, and Edith Massey, and follows delinquent high school student Dawn Davenport (played by Divine), who runs away from home, gets pregnant while hitchhiking, and embarks upon a life of crime.

Made directly after his notorious 1972 cult hit Pink Flamingos (which used much of the same cast and was made in a similar low-budget style), Waters also acted as cinematographer and co-editor. The film is dedicated to Manson Family member Charles "Tex" Watson. Waters' prison visits to Watson inspired the "crime is beauty" theme of the film and in the film's opening credits, Waters includes a wooden toy helicopter that Watson made for him.

Plot

[edit]In Baltimore in 1960, delinquent high-school student Dawn Davenport goes berserk when her parents refuse to buy her the cha-cha heels she wanted for Christmas. In a fit of rage, she topples the family Christmas tree on her mother, and storms out of the house barely even dressed. Dawn hitchhikes a ride with a repulsive, lecherous man, Earl Peterson, who drives her to a dump where they have sex on a discarded mattress. Dawn becomes pregnant, but Earl refuses to support her. She eventually gives birth to a daughter, Taffy, whom she often beats and punishes severely. Dawn works various dead-end jobs, such as a waitress in a diner, and a stripper, and engages in criminal activities such as burglary and street prostitution with her former high-school friends Concetta and Chicklette.

Dawn frequents the Lipstick Beauty Salon and marries Gater Nelson, her hair stylist and next-door neighbor. Donald and Donna Dasher, the owners of the beauty salon, recruit Dawn to be part of an artistic experiment to prove "crime and beauty are the same". They entice Dawn to commit crimes by promising her fame, and photograph her crimes to stoke her vanity.

Gater's aunt, Ida Nelson, is distraught over her nephew's marriage because she wants him to date men instead of women. When the marriage fails, Dawn persuades the Dashers to fire Gater, who moves to Detroit to work in the auto industry. Ida blames Dawn for driving Gater away and exacts revenge by throwing acid in her face, leaving Dawn hideously disfigured. The Dashers discourage Dawn from having corrective cosmetic surgery and use her as a grotesquely made-up model. They redecorate her home, and provide her with new clothes, money and make-up (which they make her inject like a drug). After they kidnap Ida and imprison her in a large birdcage as a gift to Dawn, they give Dawn an axe to chop off her hand as revenge for the acid attack.

Taffy, now a teenager, is distressed by her mother's criminal lifestyle and the fact that Dawn keeps trying to make her believe she is intellectually disabled. Taffy persuades Dawn to reveal the identity of her father, but when Taffy traces him, she finds him drunk, disheveled and living in squalor. She stabs him to death with a chef's knife after he tries to molest her. Taffy returns home, falsely claims she was unable to locate her father, and announces she is joining the Hare Krishna movement. Dawn threatens to kill her if she does.

Dawn, now with bizarre hair, make-up and outfits provided by the Dashers, mounts a nightclub act. When Taffy appears backstage in religious attire, Dawn fulfills her threat and strangles her to death. As part of her nightclub act, Dawn bounces on a trampoline, tears a phone directory into pieces, and cavorts in a crib full of dead fish. She then brandishes a gun onstage and begins firing into the crowd, wounding and killing several audience members. When police arrive to ostensibly subdue the crowd, they shoot several audience members themselves but allow the Dashers to leave when they claim to be upright citizens. Dawn flees into a forest, but is soon arrested by the police and put on trial for murder.

At the trial, the judge grants the Dashers immunity from prosecution for testifying against Dawn. The Dashers feign innocence and completely blame Dawn for the crimes she committed at their behest, and they bribe Ida to give false testimony in order to get Dawn convicted. Although Dawn's lawyer tries to have her found not guilty by reason of insanity, the jury finds Dawn guilty and sentences her to die in the electric chair. In prison, after Dawn says goodbye to her fellow inmate and lesbian lover Earnestine, she is escorted by a priest and two guards to her execution. As Dawn is strapped to the chair, she makes a speech to an imaginary audience as if she were accepting an award, and is then executed.

Cast

[edit]- Divine as Dawn Davenport / Earl Peterson

- David Lochary as Donald Dasher

- Mary Vivian Pearce as Donna Dasher

- Mink Stole as Taffy Davenport

- Hilary Taylor as young Taffy

- Edith Massey as Ida Nelson

- Cookie Mueller as Concetta

- Susan Walsh as Chicklette Friar

- Michael Potter as Gater Nelson

- Ed Peranio as Wink

- Paul Swift as Butterfly

- George Figgs as Dribbles

- Susan Lowe as Vikki

- Channing Wilroy as the prosecutor

- Elizabeth Coffey as Earnestine

Theme song

[edit]The lyrics to the title song, sung by Divine, were written by Waters and set to the instrumental track of "Black Velvet Soul" by jazz musician Cookie Thomas. The lyrics foreshadow the ending of the film with Dawn being sent to the electric chair.

Production notes

[edit]- The unique production design is by Dreamlander Vincent Peranio, who created Dawn's apartment in a condemned suite above a friend's store.

- Waters explained in a 2015 interview[2] that Dawn Davenport's look was based on the woman in the famous 1966 Diane Arbus photograph of a young Brooklyn family on a Sunday outing.[3]

- Divine chose to perform his own stunts, the most difficult of which involved doing flips on a trampoline during his nightclub act. Waters took Divine to a YMCA, where he took lessons until the act was perfected to the point where he did the athletic stunt without his wig being dislodged. Divine also nailed a difficult outdoor stunt involving crossing a real river in drag in the sleet and rain. He could have been swept downstream, but made his mark on the other side with a smile on his face.

- The birth scene was saved until the end of shooting, when Dreamlander Susan Lowe gave birth to a son and agreed to Waters' request that they film her son as Dawn's baby. The umbilical cord was fashioned out of prophylactics filled with liver, while the baby (Ramsey McLean) was doused in fake blood. The scene greatly confused Lowe's mother-in-law, who was visiting from England to meet her grandchild for the first time.[4]

- On the 2004 DVD Director's Special Comments, Waters states that the original working title of the film was "Rotten Mind, Rotten Face".[4] He changed it because he did not want to risk having hostile film critics using the headline "Rotten Mind, Rotten Face, Rotten Movie". In his book Shock Value, Waters credits Cookie Mueller with the title Female Trouble. When Mueller was hospitalized for pelvic inflammatory disease in Provincetown, Waters and Mink Stole visited her. "What happened, Cook?" Waters asked. "Just a little female trouble, hon," she replied.[5]

- This film ended up being John Waters' last time he would work with actor David Lochary. Lochary was intended to act in Waters' next film Desperate Living, but he was on PCP at the time of production. He would die months after the movie was released.

- In the trial scene, the jury consisted of many of the main cast and crew's relatives. The easiest to point out were David Lochary's (Donald Dasher) mother (who was sitting on the top row to the far right) and brother (who is in the middle in the front row); and the mother of actor Ed Peranio (Wink) and set designer Vincent Peranio (who is spotted on the top row, third from the right).

Reception

[edit]On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 90% based on 29 reviews, with an average rating of 7.1/10. The website's critics consensus reads, "Director John Waters' affection for camp brings texture to societal transgression in Female Trouble, a brazenly subversive dive into celebrity and mayhem."[6]

Where do these people come from? Where do they go when the sun goes down? Isn't there a law or something?

— Rex Reed[4]

Alternate versions

[edit]The initial 16 mm release of the film which was shown at colleges ran 92 minutes. However, when the film was blown up to 35 mm and shown theatrically, it was cut to 89 minutes. This version was the only version seen in the United States for many years. However, a recent restoration was done of the original cut, which runs 97 minutes; it has played at this 97-minute length in Europe, however, since its initial release.

The 97-minute version was shown in select theaters and was included in an out-of-print DVD set paired with Pink Flamingos (Female Trouble is still available on DVD as a single disc and as part of the DVD box set Very Crudely Yours, John Waters). This version also has a soundtrack remixed in stereo surround. The 97-minute version contains some additional scenes, including the chase through the woods, as well as an appearance by Sally Turner, the Elizabeth Taylor lookalike customer in the Lipstick Beauty Salon (Turner served as Divine's double in the junkyard sex scene between Dawn Davenport and Earl Peterson).

The film was shown in the 89-minute cut when re-released in 2002.

The 97-minute version is now available on DVD and includes an audio commentary by Waters.

The Criterion Collection released a restored version of the film on DVD and Blu-ray on June 26, 2018.[7][8]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Gage, Clint (June 26, 2022). "The Top 10 Indie Movies of All Time | A Cinefix Movie List". IGN.

- ^ "John Waters: on stage with the 'Pope of Trash'". British Film Institute. September 28, 2015. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Diane Arbus: "Arbus's Box of Ten Photographs" (2003)". American Suburb X. June 12, 2013.

- ^ a b c John Waters (2004). Female Trouble (DVD). New Line Home Entertainment.

- ^ Mandell, Jonathan (January 4, 1990). "Cookie & Vittorio". New York Newsday. p. Part II/4. Retrieved March 20, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Female Trouble". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- ^ "Female Trouble (1974)". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved June 9, 2023.

- ^ Henderson, Eric (July 2, 2018). "Blu-ray Review: John Waters's Female Trouble on the Criterion Collection". Slant Magazine. Retrieved June 9, 2023.

External links

[edit]- 1974 films

- 1974 crime films

- 1974 independent films

- 1974 LGBTQ-related films

- 1970s American films

- 1974 black comedy films

- 1970s crime comedy films

- 1970s English-language films

- American black comedy films

- American crime comedy films

- American independent films

- American LGBTQ-related films

- Cross-dressing in American films

- Drag (entertainment)-related films

- Films about female bisexuality

- Films about filicide

- Films about dysfunctional families

- Films about rape in the United States

- Films about runaways

- Films directed by John Waters

- Films produced by John Waters

- Films set in the 1960s

- Films set in Baltimore

- Films shot in Baltimore

- Films with screenplays by John Waters

- Lesbian-related films

- LGBTQ-related black comedy films

- LGBTQ-related crime comedy films

- English-language black comedy films

- English-language independent films

- English-language crime comedy films