Romanian Orthodox Church

| Romanian Orthodox Church | |

|---|---|

| Biserica Ortodoxă Română | |

Coat of arms | |

| Abbreviation | ROC (in English) BOR (in Romanian) |

| Type | Eastern Christianity |

| Classification | Eastern Orthodox |

| Scripture | Septuagint, New Testament |

| Theology | Eastern Orthodox theology |

| Polity | Episcopal |

| Primate | Daniel, Patriarch of All Romania |

| Bishops | 58 |

| Priests | 15,068[1] |

| Distinct fellowships | Ukrainian Orthodox Vicariate, Army of the Lord |

| Parishes | 15,717[1] |

| Monastics | 2,810 men, and 4,795 women[1] |

| Monasteries | 359[1] |

| Associations | Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Language | Romanian |

| Liturgy | Byzantine Rite |

| Headquarters | Dealul Mitropoliei, Bucharest |

| Territory | Romania Moldova[a] |

| Possessions | Serbia Hungary Western and Southern Europe; Germany, Central and Northern Europe; Americas; Australia and New Zealand |

| Founder | (as Metropolis of Romania) Nifon Rusailă, Carol I (as Patriarchate of Romania) Miron Cristea, Ferdinand I |

| Independence | 1865 |

| Recognition | 25 April 1885 (Autocephalous metropolis) 1925 (Autocephalous Patriarchate) |

| Absorbed | Romanian Greek Catholic Church (1948) |

| Separations | Old Calendarist Romanian Orthodox Church (1925) Evangelical Church of Romania (1927) Romanian Greek Catholic Church (1990) |

| Members | 16,367,267 in Romania;[2] 720,000 in Moldova[3] 11,203 in United States[4] |

| Publications | Ziarul Lumina |

| Official website | patriarhia.ro |

| Part of a series on the |

| Eastern Orthodox Church |

|---|

| Overview |

The Romanian Orthodox Church (ROC; Romanian: Biserica Ortodoxă Română, BOR), or Patriarchate of Romania, is an autocephalous Eastern Orthodox church in full communion with other Eastern Orthodox Christian churches, and one of the nine patriarchates in the Eastern Orthodox Church. Since 1925, the church's Primate has borne the title of Patriarch. Its jurisdiction covers the territories of Romania and Moldova, with additional dioceses for Romanians living in nearby Serbia and Hungary, as well as for diaspora communities in Central and Western Europe, North America and Oceania. It is the only autocephalous church within Eastern Orthodoxy to have a Romance language for liturgical use.

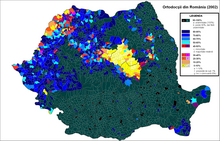

The majority of Romania's population (16,367,267, or 85.9% of those for whom data were available, according to the 2011 census data[5]), as well as some 720,000 Moldovans,[3] belong to the Romanian Orthodox Church.

Members of the Romanian Orthodox Church sometimes refer to Orthodox Christian doctrine as Dreapta credință ("right/correct belief" or "true faith"; compare to Greek ὀρθὴ δόξα, "straight/correct belief").[citation needed]

History

[edit]

In the Principalities and the Kingdom of Romania

[edit]The Orthodox hierarchy in the territory of modern Romania had existed within the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople until 1865 when the churches in the Romanian principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia embarked on the path of ecclesiastical independence by nominating Nifon Rusailă, Metropolitan of Ungro-Wallachia, as the first Romanian primate. Prince Alexandru Ioan Cuza, who had in 1863 carried out a mass confiscation of monastic estates in the face of stiff opposition from the Greek hierarchy in Constantinople, in 1865 pushed through a legislation that proclaimed complete independence of the church in the principalities from the patriarchate.

In 1872, the Orthodox churches in the principalities, the Metropolis of Ungro-Wallachia and the Metropolis of Moldavia, merged to form the Romanian Orthodox Church.

Following the international recognition of the independence of the United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia (later Kingdom of Romania) in 1878, after a long period of negotiations with the Ecumenical Patriarchate, Patriarch Joachim IV granted recognition to the autocephalous Metropolis of Romania in 1885, which was raised to the rank of Patriarchate in 1925.[6]

Romanian Orthodox theological education was underdeveloped at the end of the nineteenth century. The theological institute at Sibiu, for example, had only one theologian as part of its faculty; the rest were historians, journalists, naturalists, and agronomists. The focus of priestly education was practical and general rather than specialized. In the early twentieth century, the curriculum of a priest included subjects such as hygiene, calligraphy, accountancy, psychology, Romanian literature, geometry, chemistry, botany, and gymnastics. A strong emphasis was placed on church music, canon law, church history, and exegesis.[7]

After World War I, the Kingdom of Romania significantly increased its territory. Consequently, the Romanian Orthodox Church needed massive reorganization in order to incorporate congregations from these new provinces. This led to shortages and difficulties. The Church had to establish a uniform interpretation of canon law. It had to handle public funds for paying clergymen in the newly acquired territories and, generally speaking, manage the relationship with the state. The legislation was intricate. The Statute on the organization of the Romanian Orthodox Church adopted by the Romanian parliament on May 6, 1925, counted 178 articles. The law on the functioning of the Romanian Orthodox Church counted 46 articles. Legislators adopted the Transylvanian tradition of mixing clergymen and laymen in administrative assemblies and granted bishops seats in the Romanian Senate.[8] However, the context also allowed a number of young theologians like Nichifor Crainic, Ioan Savin, or Dumitru Stăniloae to study abroad. These theologians proved extremely influential after their return to Romania and helped shape theological academies. With a few rare exceptions, like Gala Galaction, the Romanian Orthodox theologians of this period embraced nationalism. Their scholarly works are thus imbued with nationalist ideology.[7]

The second half of the 1920s is marked by the rise of antisemitism in Romanian politics with figures such as A.C. Cuza or Iron Guard founding father Codreanu. Antisemitism also became apparent in church publications. In 1925, for instance, church journal Revista Teologică (The Theological Review) published an anti-Semitic article by Sibiu professor priest Pompiliu Morușca. Morușca's article blamed the Jews for the economic situation of Romanians in Bukovina. It is a testimony of an older form of anti-Semitism going back to the 19th century. The Romanian Orthodox Church would evolve different forms of antisemitism in the 1930s.[9] The Concordat of 1927 also triggered anti-Catholic reactions.[8]

1930s - Patriarch Miron Cristea's premiership

[edit]The rise of Nazi Germany exposed Romania to the Reich's theological ideas. This mixture of nationalism, racism and theological thought found fertile ground in a Romanian Orthodox Church that was already no stranger to antisemitism. It became particularly evident in the second half of the 1930s in the writings of theologians such as Nichifor Crainic, Nicolae Neaga or Liviu Stan.[9]

In 1936, Crainic published a seminal text titled Rasă și religiune (Race and Religion). While rejecting the Nazi idea of a superior Germanic race, as well as the fascination with Germanic paganism, Crainic argued that some races are indeed superior based on their accomplishment of the Christian essence. Crainic also denied the Jews the moral right to use the books of the Old Testament since, according to him, those prophesies had been fulfilled by the coming of Christ who had abolished the Jewish religion.[9]

The deaths of prominent Iron Guard members Ion Moța and Vasile Marin on the same day, January 13, 1937, at Majadahonda during the Spanish Civil War while fighting for the Nationalist faction led to the organization of massive processions in Romania, particularly in Bucharest where they were interred. Hundreds of Orthodox priests participated and Metropolitans Nicolae Bălan of Transylvania and Visarion Puiu of Bukovina held special services.[10][9] Shortly after the funeral, Orthodox theologian Gheorghe Racoveanu and priest Grigore Cristescu founded the theological journal Predania (The Tradinion). The first issue featured a glorification of Moța and Marin and their sacrifice and reflected the Guard's obsession for martyrdom. Intended as a bi-monthly Predania printed a total of twelve issues before being banned by the authorities. It stood out for its profoundly anti-ecumenical editorial line, publishing attacks against Catholics, Protestants, Evangelicals.[8]

Also in the aftermath of Moța and Marin's grandiose funeral, the Holy Synod issued a condemnation of Freemasonry. Moreover, following the lead of Metropolitan Bălan who wrote the anti-Masonic manifest, the Synod issued a "Christian point of view" against political secularism stating that the Church was in its right to choose which party was worthy of support, based on its moral principles. Iron Guard leader Codreanu saluted the Synod's position and instructed that the Synod's proclamation should be read by Guard members in their respective nests (i.e. chapters).[9]

In 1937, the Goga-Cuza government was the first to adopt and enact antisemitic legislation in the Kingdom of Romania, stripping over two hundred thousand Jews of their citizenship. That very same year, the head of the Romanian Orthodox Church, Patriarch Cristea made an infamous speech in which he described the Jews as parasites who suck the bone marrow of the Romanian people and who should leave the country.[11] The Orthodox church directly or indirectly supported far-right parties and antisemitic intellectuals in their anti-Jewish rhetoric.[12] At the time many Orthodox priests had become active in far-right politics, thus in the 1937 parliamentary elections 33 out of 103 Iron Guard candidates were Orthodox priests.[11]

Overall, the church became increasingly involved in politics and, after King Carol II assumed emergency powers, Patriarch Miron Cristea became prime-minister in February 1938. In March 1938, the Holy Synod banned the conversion of Jews who were unable to prove their Romanian citizenship.[13] Cristea continued the policies of the Goga-Cuza government but also advocated more radical antisemitic measures including deportation and exclusion from employment. Cristea referred to this last measure as "Romanianization". The church newspaper Apostolul was instrumental in propagating Cristea's antisemitic ideas throughout his premiership but church press as a whole became flooded with antisemitic materials.[14] Miron Cristea died in March 1939. Soon after, the Holy Synod voted to uphold regulations adopted under Cristea banning the baptism of Jews who were not Romanian citizens.[14]

Cristea's death led to elections being held in order to select a new Patriarch. Metropolitans Visarion Puiu and the highly influential Nicolae Bălan publicly declared their refusal to enter the race. Both of these bishops held pro-German, pro-Iron-Guard and antisemitic views and it is reasonable to assume that King Carol II's opposition was instrumental in their refusal. Thus, the patriarchal office passed to a reluctant Nicodim Munteanu.[15]

1940s - World War II

[edit]King Carol II abdicated on September 6, 1940. An openly pro-German coalition of the military headed by marshal Ion Antonescu and the Iron Guard took over. Patriarch Nicodim Munteanu's reaction was cautious and his September 1940 address was unenthusiastic. Munteanu, like Cristea before him, feared the anti-establishment nature of the Guard. But the Iron Guard was highly influential on the Church's grassroots. In January 1941, seeking full control of the country, the Iron Guard attempted a violent insurrection known as the Legionary Rebellion. The putsch failed and out of the 9000 people arrested, 422 were Orthodox priests.[16]

Some particularly violent episodes during the insurrection directly involved the Orthodox clergy. Students and staff of the Theological Academy in Sibiu, led by Professor Spiridon Cândea and assisted by Iron Guard militiamen rounded up Jews in the courtyard of the academy and forced them to hand over their valuables at gunpoint. Monks from the Antim Monastery in Bucharest, led by their abbot, armed themselves and, using explosives, blew up a Synagogue on Antim Street. The numerous Jewish inhabitants of the neighborhood hid in terror.[17]

After Antonescu and the Army crushed the insurrection, the Holy Synod was quick to condemn the Legionary Rebellion and publicly paint it as a diabolical temptation that had led the Iron Guard to undermine the state and the Conducător. Many of the clergymen who had participated in the Rebellion were, however, shielded by their bishops and continued parish work in remote villages. Romania's participation in World War II on the Axis side after June 1941 would provide them with opportunities for rehabilitation.[17]

By the early 1940s, Orthodox theologians such as Nichifor Crainic already had a lengthy record of producing propaganda supporting the concept of Judeo-Bolshevism. After 1941 the idea became commonplace in central church newspapers such as Apostolul or BOR. A particularly infamous article was signed by Patriarch Nicodim himself and published in BOR in April 1942. It referred to the danger of domestic enemies whom he identified as mostly being Jewish.[18] In 1943 BOR published a 13-page laudatory review of Nichifor Crainic's infamous antismetic book Transfigurarea Românismului (The Transfiguration of Romanianism).[19] Antisemitism was also present in regional journals,[20] a leading example being Dumitru Stăniloae's Telegraful român (The Romanian Telegraph).[21] Orthodox chaplains in the Romanian army cultivated the Judeo-Bolshevik myth.[22]

A particular case was Romanian-occupied Transnistria. On August 15, 1941, The Holy Synod established a mission, rather than a new bishopric, in Romanian-occupied territories across the Dniester. The assumption was that Soviet atheist rule had destroyed the Russian Orthodox Church and the Romanian Orthodox Church took it upon itself to "re-evangelize" the locals. The main architect of the enterprise was Archimandrite Iuliu Scriban. In 1942 the Mission evolved into an Exarchate and was taken over by Visarion Puiu. Many of the missionaries were former affiliates of the Iron Guard, some were seeking rehabilitation after the 1941 insurrection. Abuse against the Jewish population was widespread and numerous reports of Orthodox priests partaking and profiting from the abuse exist.[17] In 1944, Visarion Puiu fled to Nazi Germany, then, after the war, in the West. In Romania he was tried and convicted in absentia after the war. Many priests active in Transnistria also faced prosecution after the war, although communist prosecutors were mostly looking for connections to the Iron Guard, rather than explicitly investigating the persecution of Jews.[23]

Historical evidence regarding the Romanian Orthodox Church's role in World War II is overwhelmingly incriminating but there are a few exceptions.[24] Tit Simedrea, metropolitan of Bukovina is one two high-ranking bishops known to have interceded in favor of the Jewish population, the other being the metropolitan Nicolae Bălan of Transylvania. Evidence also surfaced that Simedrea personally sheltered a Jewish family in the metropolitanate compound. [25] Priest Gheorghe Petre was recognized as Righteous Among the Nations for having saved Jews in Kryve Ozero. Petre was arrested in 1943 and court-martialed but was released in 1944 for lack of evidence.[26]

After King Michael's Coup on August 23, 1944, Romania switched sides. The coup had been backed by the communists; the Church, known for its long-term record of anti-Soviet and anti-communist rhetoric now found itself in an awkward position.[27] Patriarch Nicodim was quick to write a pastoral letter denouncing the previous dictatorship, blaming the Germans for the events that had taken place in Romania during the 30s and during the war and praising "the powerful neighbor from the East" with whom Romania had, supposedly, always had "the best political, cultural, and religious relations."[28]

Starting in 1944, and even more after Petru Groza became Prime-minister with Soviet support in 1945, the Church tried to adapt to the new political situation. In August 1945 a letter of the Holy Synod was published in BOR. Again, it blamed the Germans for the horrors of the war and claimed that the Orthodox Church had always promoted democracy. The Romania Army was also praised for having joined forces with "the brave Soviet armies in the war against the true adversaries of our country." Finally, the Orthodox faithful were asked to fully support the new government.[29] Later that year BOR published two relatively long articles authored by Bishop Antim Nica and, respectively, by Teodor Manolache. Both articles dealt with the Holocaust and painted the Romanian Orthodox Church as a savior of Jews.[30]

Communist period

[edit]

Romania officially became a communist state in 1947. Restricted access to ecclesiastical and relevant state archives[31]: 446–447 [32] makes an accurate assessment of the Romanian Orthodox Church's attitude towards the Communist regime a difficult proposition. Nevertheless, the activity of the Orthodox Church as an institution was more or less tolerated by the Marxist–Leninist atheist regime, although it was controlled through "special delegates" and its access to the public sphere was severely limited; the regime's attempts at repression generally focused on individual believers.[31]: 453 The attitudes of the church's members, both laity and clergy, towards the communist regime, range broadly from opposition and martyrdom, to silent consent, collaboration or subservience aimed at ensuring survival. Beyond limited access to the Securitate and Party archives as well as the short time elapsed since these events unfolded, such an assessment is complicated by the particularities of each individual and situation, the understanding each had about how their own relationship with the regime could influence others and how it actually did.[31]: 455–456 [33]

The Romanian Workers' Party, which assumed political power at the end of 1947, initiated mass purges that resulted in a decimation of the Orthodox hierarchy. Three archbishops died suddenly after expressing opposition to government policies, and thirteen more "uncooperative" bishops and archbishops were arrested.[34] A May 1947 decree imposed a mandatory retirement age for clergy, thus providing authorities with a convenient way to pension off old-guard holdouts. The 4 August 1948 Law on Cults institutionalised state control over episcopal elections and packed the Holy Synod with Communist supporters.[35] The evangelical wing of the Romanian Orthodox Church, known as the Army of the Lord, was suppressed by communist authorities in 1948.[36] In exchange for subservience and enthusiastic support for state policies, the property rights over as many as 2,500 church buildings and other assets belonging to the (by then-outlawed) Romanian Greek-Catholic Church were transferred to the Romanian Orthodox Church; the government took charge of providing salaries for bishops and priests, as well as financial subsidies for the publication of religious books, calendars and theological journals.[37] By weeding out the anti-communists from among the Orthodox clergy and setting up a pro-regime, secret police-infiltrated Union of Democratic Priests (1945), the party endeavoured to secure the hierarchy's cooperation. By January 1953 some 300-500 Orthodox priests were being held in concentration camps, and following Patriarch Nicodim's death in May 1948, the party succeeded in having the ostensibly docile Justinian Marina elected to succeed him.[34]

As a result of measures passed in 1947–48, the state took over the 2,300 elementary schools and 24 high schools operated by the Orthodox Church. A new campaign struck the church in 1958-62 when more than half of its remaining monasteries were closed, more than 2,000 monks were forced to take secular jobs, and about 1,500 clergy and lay activists were arrested (out of a total of up to 6,000 in the 1946-64 period[37]). Throughout this period Patriarch Justinian took great care that his public statements met the regime's standards of political correctness and to avoid giving offence to the government;[38] indeed the hierarchy at the time claimed that the arrests of clergy members were not due to religious persecution.[35]

The church's situation began to improve in 1962, when relations with the state suddenly thawed, an event that coincided with the beginning of Romania's pursuit of an independent foreign policy course that saw the political elite encourage nationalism as a means to strengthen its position against Soviet pressure. The Romanian Orthodox Church, an intensely national body that had made significant contributions to Romanian culture from the 14th century on, came to be regarded by the regime as a natural partner. As a result of this second co-optation, this time as an ally, the church entered a period of dramatic recovery. By 1975, its diocesan clergy was numbering about 12,000, and the church was already publishing by then eight high-quality theological reviews, including Ortodoxia and Studii Teologice. Orthodox clergymen consistently supported the Ceaușescu regime's foreign policy, refrained from criticizing domestic policy, and upheld the Romanian government's line against the Soviets (over Bessarabia) and the Hungarians (over Transylvania). As of 1989, two metropolitan bishops even sat in the Great National Assembly.[38] The members of the church's hierarchy and clergy remained mostly silent as some two dozen historic Bucharest churches were demolished in the 1980s, and as plans for systematization (including the destruction of village churches) were announced.[39] A notable dissenter was Gheorghe Calciu-Dumitreasa, imprisoned for a number of years and eventually expelled from Romania in June 1985, after signing an open letter criticizing and demanding an end to the regime's violations of human rights.[37]

In an attempt to adapt to the newly created circumstances, the Eastern Orthodox Church proposed a new ecclesiology designed to justify its subservience to the state in supposedly theological terms. This so-called "Social Apostolate" doctrine, developed by Patriarch Justinian, asserted that the church owed allegiance to the secular government and should put itself at its service. This notion inflamed conservatives, who were consequently purged by Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, Ceaușescu's predecessor and a friend of Justinian's. The Social Apostolate called on clerics to become active in the People's Republic, thus laying the foundation for the church's submission to and collaboration with the state. Fr. Vasilescu, an Orthodox priest, attempted to find grounds in support of the Social Apostolate doctrine in the Christian tradition, citing Augustine of Hippo, John Chrysostom, Maximus the Confessor, Origen and Tertullian. Based on this alleged grounding in tradition, Vasilescu concluded that Christians owed submission to their secular rulers as if it were the will of God. Once recalcitrants were removed from office, the remaining bishops adopted a servile attitude, endorsing Ceauşescu's concept of nation, supporting his policies, and applauding his peculiar ideas about peace.[40]

Collaboration with the Securitate

[edit]In the wake of the Romanian Revolution, the church never admitted to having ever willingly collaborated with the regime, although several Romanian Orthodox priests have publicly admitted after 1989 that they had collaborated with and/or served as informers for the Securitate, the secret police. A prime example was Bishop Nicolae Corneanu, the Metropolitan of Banat, who admitted to his efforts on behalf of the Romanian Communist Party, and denounced activities of clerics in support of the Communists, including his own, as "the Church's [act of] prostitution with the Communist regime".[35]

In 1986, Metropolitan Antonie Plămădeală defended Ceaușescu's church demolition programme as part of the need for urbanization and modernisation in Romania.[41] The church hierarchy refused to try to inform the international community about what was happening.[42]

Widespread dissent from religious groups in Romania did not appear until revolution was sweeping across Eastern Europe in 1989. The Patriarch of the Romanian Orthodox Church Teoctist Arăpașu supported Ceaușescu up until the end of the regime, and even congratulated him after the state murdered one hundred demonstrators in Timișoara.[43] It was not until the day before Ceaușescu's execution on 24 December 1989 that the Patriarch condemned him as "a new child-murdering Herod".[43]

Following the removal of Communism, the Patriarch resigned (only to return a few months after) and the Holy Synod apologised for those "who did not have the courage of the martyrs".[41]

After 1989

[edit]

As Romania made the transition to democracy, the church was freed from most of its state control, although the State Secretariat for Religious Denominations still maintains control over a number of aspects of the church's management of property, finances and administration. The state provides funding for the church in proportion to the number of its members, based on census returns[44] and "the religion's needs" which is considered to be an "ambiguous provision".[45] Currently, the state provides the funds necessary for paying the salaries of priests, deacons and other prelates and the pensions of retired clergy, as well as for expenses related to lay church personnel. For the Orthodox church this is over 100 million euros for salaries,[46] with additional millions for construction and renovation of church property. The same applies to all state-recognised religions in Romania.

The state also provides support for church construction and structural maintenance, with a preferential treatment of Orthodox parishes.[47] The state funds all the expenses of Orthodox seminaries and colleges, including teachers' and professors' salaries who, for compensation purposes, are regarded as civil servants.

Since the fall of Communism, Greek-Catholic Church leaders have claimed that the Eastern Catholic community is facing a cultural and religious wipe-out: the Greek-Catholic churches are allegedly being destroyed by representatives of the Eastern Orthodox Church, whose actions are supported and accepted by the Romanian authorities.[48]

The church openly supported banning same-sex marriage in a referendum in 2018.[49][50] The church believes that homosexuality is a sin and unnatural.[51]

In the Republic of Moldova

[edit]The Romanian Orthodox Church also has jurisdiction over a minority of believers in Moldova, who belong to the Metropolis of Bessarabia, as opposed to the majority, who belong to the Metropolis of Chișinău and All Moldova, under the Moscow Patriarchate. In 2001 it won a landmark legal victory against the Government of Moldova at the Strasbourg-based European Court of Human Rights.

This means that despite current political issues, the Metropolis of Bessarabia is now recognized as "the rightful successor" to the Metropolitan Church of Bessarabia and Hotin, which existed from 1927 until its dissolution in 1944, when its canonical territory was put under the jurisdiction of the Russian Orthodox Church's Moscow Patriarchate in 1947.

After the debut of the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Romanian Orthodox Church in Moldova has seen a significant number of parishes switching afilliation from the Moscow controlled Metropolis of Chișinău and All Moldova to the Metropolis of Bessarabia, sometimes smoothly, otherwise through intense debates and highly polemicized switches.[52][53][54][55]

Organization and leadership

[edit]

The Romanian Orthodox Church is organized in the form of the Romanian Patriarchate. The highest hierarchical, canonical and dogmatical authority of the Romanian Orthodox Church is the Holy Synod.

There are ten Orthodox Metropolitanates, twenty archbishoprics, twenty-three bishoprics in total, of which four metropolitans and nine bishops administer the Church services for the Romanian Diaspora in Europe, the Americas, Asia and Oceania. An estimated number of over twelve thousand altar servers in parishes, monasteries and social centres of the Church. Almost 400 monasteries exist inside the country, staffed by some 3,500 monks and 5,000 nuns. As of 2004, there are, inside Romania, fifteen theological universities where more than ten thousand students (some of them from Bessarabia, Bukovina and Serbia benefiting from a few Romanian fellowships) currently study for a theological degree. More than 14,500 churches (traditionally named "lăcașe de cult", or houses of worship) exist in Romania for the Romanian Orthodox believers. As of 2002, almost 1,000 of those were either in the process of being built or rebuilt[citation needed].

Current leadership

[edit]The patriarchal chair is currently held by His Beatitude Daniel, Archbishop of Bucharest, Metropolitan of Muntenia and Dobrudja, Locum Tenens of Caesarea in Cappadocia and Patriarch of the Romanian Orthodox Church.[56][57] The title of Locum tenens of Caesarea in Cappadocia is a titular office granted in 1776 by Ecumenical Patriarch Sophronius II[58][59] to the holder of the office of Metropolitan of Ungro-Wallachia, the precursor position of the Orthodox Church to the today Patriarchate of Romania.

- Teofan, Metropolitan of Moldavia and Bukovina[60]

- Laurențiu, Metropolitan of Transylvania[61]

- Andrei, Metropolitan of Cluj, Maramureș and Sălaj[62]

- Irineu, Metropolitan of Oltenia[63]

- Ioan, Metropolitan of Banat[64]

- Petru, Metropolitan of Bessarabia[65]

- Iosif, Metropolitan of Western and Southern Europe[66]

- Serafim, Metropolitan of Germany and Central Europe[67]

- Nicolae, Metropolitan of the Americas[68]

Notable theologians

[edit]Dumitru Stăniloae (1903–1993) is considered one of the greatest Orthodox theologians of the 20th century, having written extensively in all major fields of Eastern Christian systematic theology. One of his other major achievements in theology is the 45-year-long comprehensive series on Orthodox spirituality known as the Romanian Philokalia, a collection of texts written by classical Byzantine writers, that he edited and translated from Greek.

Archimandrite Cleopa Ilie (1912–1998), elder of the Sihăstria Monastery, is considered one of the most representative fathers of contemporary Romanian Orthodox monastic spirituality.[69]

Metropolitan Bartolomeu Anania (1921-2011) was the Metropolitan of Cluj, Alba, Crișana and Maramureș from 1993 until his death.

List of patriarchs

[edit]- Miron (1925–1939)

- Nicodim (1939–1948)

- Justinian (1948–1977)

- Iustin (1977–1986)

- Teoctist (1986–2007)

- Daniel (since 2007)

Jubilee and commemorative years

[edit]Initiative of Patriarch Daniel’s, with a deep missionary impact for Church and society, has been the proclamation of jubilee and commemorative years in the Romanian Patriarchate, with solemn sessions of the Holy Synod, conferences, congresses, monastic synaxes, debates, programmes of catechesis, processions and other Church activities dedicated to the respective annual theme.

- 2008 – The Jubilee Year of the Holy Scripture and the Holy Liturgy;

- 2009 – The Jubilee-Commemorative year of Saint Basil the Great, Archbishop of Cæsarea in Cappadocia;

- 2010 – The Jubilee Year of the Orthodox Creed and of Romanian Autocephaly;

- 2011 – The Jubilee Year of Holy Baptism and Holy Matrimony;

- 2012 – The Jubilee Year of Holy Unction and of the care for the sick;

- 2013 – The Jubilee Year of the Holy Emperors Constantine and Helena;

- 2014 – The Jubilee Year of the Eucharist (of the Holy Confession and of the Holy Communion) and the Commemorative Year of the Martyr Saints of the Brancoveanu family;

- 2015 – The Jubilee Year of the Mission of Parish and Monastery Today and the Commemorative Year of Saint John Chrysostom and of the great spiritual shepherds in the eparchies;

- 2016 – The Jubilee Year of Religious Education for Orthodox Youth and the Commemorative Year of the Holy Hierarch and Martyr Antim of Iveria and of all the printing houses of the Church;

- 2017 – The Jubilee Year of the Holy Icons and of church painters and the Commemorative Year of Patriarch Justin and of all defenders of Orthodoxy during communism;

- 2018 – The Jubilee Year of Unity of Faith and Nation, and the Commemorative Year of the 1918 Great Union Founders;

- 2019 – Solemn Year of church singers and of the Commemorative Year of Patriarch Nicodim and of the translators of church books;

- 2020 – Solemn Year of Ministry to Parents and Children and the Commemorative Year of Romanian Orthodox Philanthropists;

- 2021 – Solemn Year of pastoral care of Romanians abroad and the Commemorative Year of the reposed in the Lord;

- 2022 – Solemn Year of Prayer in the Church’s life and the Christian’s life and the Commemorative Year of the Hesychast Saints Symeon the New Theologian, Gregory Palamas and Paisius of Neamț;

- 2023 – Solemn Year of the Pastoral Care of the Elderly and the Commemorative Year of the Hymnographers and Church Chanters;

- 2024 – Solemn Year of the pastoral care of the sick and the Commemorative Year of all the holy unmercenary healers;

- 2025 – The Jubilee Year of the Centennial of the Romanian Patriarchate and the Commemorative Year of the Romanian Orthodox confessors of the twentieth century.;

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Disputed with the Russian Orthodox Church.

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d Reichel & Eder 2011, p. 25.

- ^ 2011 Romanian census.

- ^ a b "Biserica Ortodoxă Română, atacată de bisericile 'surori'" [The Romanian Orthodox Church, Attacked by Its 'Sister' Churches]. Ziua (in Romanian). 31 January 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-02-01.

- ^ Krindatch 2011, p. 143.

- ^ "2011 census data on religion" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-09-20. Retrieved 2012-10-29.

- ^ Hitchins 1994, p. 92.

- ^ a b Clark 2009.

- ^ a b c Biliuță 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Biliuță 2016.

- ^ Popa 2017, p. 26.

- ^ a b Popa 2017, p. 27.

- ^ Popa 2017, p. 20.

- ^ Popa 2017, p. 53.

- ^ a b Popa 2017, p. 33.

- ^ Popa 2017, p. 34.

- ^ Popa 2017, p. 36.

- ^ a b c Biliuță 2020.

- ^ Popa 2017, p. 45.

- ^ Popa 2017, p. 46.

- ^ Popa 2017, p. 49.

- ^ Gabriel Andreescu, Anti-Semitic issues in Orthodox publications, years 1920-1944, Civitas Europica Centralis, 2014

- ^ Popa 2017, p. 51.

- ^ Popa 2017, p. 50.

- ^ Popa 2017, p. 57.

- ^ Popa 2017, p. 58.

- ^ Popa 2017, p. 61.

- ^ Popa 2017, p. 83.

- ^ Popa 2017, p. 83-84.

- ^ Popa 2017, p. 86-87.

- ^ Popa 2017, p. 88-95.

- ^ a b c Presidential Commission for the Study of the Communist Dictatorship in Romania (2006). "Raport final" (PDF) (in Romanian). Romanian Presidency.

- ^ Neamțu 2007.

- ^ Enache 2006.

- ^ a b Ramet 1989, pp. 19–20.

- ^ a b c Stan & Turcescu 2007.

- ^ Maclear 1995, p. 485.

- ^ a b c Ramet 2004, p. 278.

- ^ a b Ramet 1989, p. 20.

- ^ Ramet 2004, p. 279.

- ^ Ramet 2004, p. 280.

- ^ a b Stan & Turcescu 2000.

- ^ Stan & Turcescu 2006.

- ^ a b Ediger 2005.

- ^ Fox 2008, p. 167.

- ^ "International Religious Freedom - Embassy of the United States Bucharest, Romania". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ^ Dunlop 2013.

- ^ Iordache 2003, p. 253.

- ^ "The Romanian Greek-Catholic Community is facing a cultural and religious wipe-out – letter to US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton". HotNewsRo. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ^ Molloy, David (6 October 2018). "Romania marriage poll: One man, one woman definition up for vote". BBC News. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- ^ Verseck, Keno (11 August 2021). "Will Romania step up anti-LGBTQ legislation like Hungary?". Deutsche Welle (DW). Retrieved 7 September 2022.

Although a referendum seeking to prevent same-sex marriage from ever being legalized was held in 2018 after being championed by the Romanian Orthodox Church, it failed after only 21% of eligible voters turned up to cast their ballot.

- ^ "Romanian Orthodox Church steps up propaganda before referendum for family". Romania Insider. 1 October 2018. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- ^ Conovali, Mihaela (2024-02-27). "„Neascultare şi nesupunere". Plus un preot la Mitropolia Basarabiei, minus - de la Mitropolia Moldovei". NewsMaker (in Romanian). Retrieved 2024-06-29.

- ^ "Preotul Alexandru NOROȘEAN, parohul bisericii „Acoperemântul Maicii Domnului" din s. Stolniceni, r. Hîncești, a fost oprit de a săvârși cele sfinte". Episcopia Ungheni (in Romanian). 2024-02-26. Retrieved 2024-06-29.

- ^ Шоларь, Евгений (2023-11-17). "Biserica pro-rusă din Moldova se orientează spre România? Explicăm „exodul" preoților și analizăm posibilele scenarii". NewsMaker (in Romanian). Retrieved 2024-06-29.

- ^ Cucu, Preot Ilie (2023-10-30). "Comunicat de presă cu privire la unele acuzații nefondate ale sinodului Mitropoliei Chișinăului (Patriarhia Moscovei), aflate în faliment instituțional". Mitropolia Basarabiei (in Romanian). Retrieved 2024-06-29.

- ^ "Organizarea Administrativă". patriarhia.ro. Retrieved 2024-06-29.

- ^ "Patriarhia Română". patriarhia.ro. Retrieved 2024-06-29.

- ^ Țipău 2004, p. 89.

- ^ Semen & Petcu 2009, p. 635.

- ^ "Înaltpreasfinţitul Teofan Arhiepiscop al Iașilor și Mitropolit al Moldovei și Bucovinei | Mitropolia Moldovei și Bucovinei - Arhiepiscopia Iașilor". mmb.ro. Retrieved 2024-06-29.

- ^ "Mitropolitul". Mitropolia Ardealului. Retrieved June 29, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Înaltpreasfinţitul Andrei, Mitropolitul Clujului, Maramureșului și Sălajului". Mitropolia Clujului (in Romanian). Retrieved 2024-06-29.

- ^ "ÎPS Mitropolit Academician Dr. IRINEU". Mitropolia Olteniei (in Romanian). 2024-06-04. Retrieved 2024-06-29.

- ^ "IPS IOAN SELEJAN, Arhiepiscopul Timişoarei şi Mitropolitul Banatului | Mitropolia Banatului | Arhiepiscopia Timişoarei". Retrieved 2024-06-29.

- ^ "Ierarhi". Mitropolia Basarabiei (in Romanian). Retrieved 2024-06-29.

- ^ "Mitropolia". www.mitropolia.eu. Retrieved 2024-06-29.

- ^ "Înaltpreasfințitul Mitropolit Serafim al Germaniei, Europei Centrale și de Nord". Mitropolia Ortodoxă Română a Germaniei, Europei Centrale și de Nord (in Romanian). 2014-01-25. Retrieved 2024-06-29.

- ^ "Biography". www.mitropolia.us. Retrieved 2024-06-29.

- ^ Electronic version of Dicționarul teologilor români (Dictionary of Romanian Theologians), Univers Enciclopedic Ed., Bucharest, 1996, retrieved from http://biserica.org/WhosWho/DTR/I/IlieCleopa.html Archived 2011-09-16 at the Wayback Machine.

Sources

[edit]- Biliuță, Ionuț (2016). "Sowing the Seeds of Hate. The Antisemitism of the Romanian Orthodox Church in the Interwar Period". S.I.M.O.N. - Shoah: Intervention, Methods, Documentation. 3 (1): 20–34.

- Biliuță, Ionuț (2018). "The Ultranationalist Newsroom: Orthodox "Ecumenism" in the Legionary Ecclesiastical Newspapers". Sciendo. 10 (2): 186–211. doi:10.2478/ress-2018-0015.

- Biliuță, Ionuț (2020). ""Christianizing" Transnistria: Romanian Orthodox Clergy as Beneficiaries, Perpetrators, and Rescuers during the Holocaust". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 34 (1): 18–44. doi:10.1093/hgs/dcaa003.

- Clark, Roland (2009). "Nationalism, Ethnotheology, and Mysticism in Interwar Romania". The Carl Beck Papers in Russian and East European Studies (2002): 51. doi:10.5195/cbp.2009.147.

- Dunlop, Tessa (7 August 2013). "Romania's costly passion for building churches". BBC News. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- Ediger, Ruth M. (2005). "History of an institution as a factor for predicting church institutional behavior: the cases of the Catholic Church in Poland, the Orthodox Church in Romania, and the Protestant churches in East Germany". East European Quarterly. 39 (3). Gale A137013797.

- Enache, George (2 September 2006). "Biserica Ortodoxă Română și Securitatea" [Romanian Orthodox Church and Security] (in Romanian). Ziua. Archived from the original on 2007-02-18.

- Fox, Jonathan (2008). A World Survey of Religion and the State. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511993039. ISBN 978-1-139-47259-3.

- Hitchins, Keith (1994). Romania 1866-1947. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Iordache, Romanita E. (2003). "Church and State in Romania". In Ferrari, Silvio; Durham, W. Cole; Sewell, Elizabeth A. (eds.). Law and Religion in Post-communist Europe. Peeters. ISBN 978-90-429-1262-5.

- Krindatch, Alexei, ed. (2011). Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Churches. Brookline, MA: Holy Cross Orthodox Press. ISBN 978-1-935317-23-4.

- Maclear, J. F. (1995). Church and State in the Modern Age: A Documentary History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-508681-2.

- Neamțu, Mihail (2007-10-17). "Despărțirea apelor: Biserica și Securitatea" (in Romanian). Revista 22. Archived from the original on 2009-04-22.

- Popa, Ion (11 September 2017). The Romanian Orthodox Church and the Holocaust (Kindle ed.). Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-02989-8.

- Ramet, Pedro, ed. (1989). Religion and Nationalism in Soviet and East European Politics. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-0891-6. OCLC 781990204.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2004). "Church and State in Romania before and after 1989". In Carey, Henry F. (ed.). Romania Since 1989: Politics, Economics, and Society. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-0592-4.

- Reichel, Walter; Eder, Thomas, eds. (2011), "Religions in Austria", Federal Press Service, Vienna: Federal Chancery, Federal Press Service, p. 25, archived from the original on 2013-10-13, retrieved 2 July 2013

- Semen, Petre; Petcu, Liviu (2009). Părinţii Capadocieni. Editura Fundației Academice AXIS. ISBN 978-973-7742-80-3. OCLC 895458085.

- Stan, Lavinia; Turcescu, Lucian (2000). "The Romanian Orthodox Church and Post-communist Democratisation". Europe-Asia Studies. 52 (8): 1467–1488. doi:10.1080/713663138. ISSN 0966-8136. S2CID 144380554.

- Stan, Lavinia; Turcescu, Lucian (2006). "Politics, national symbols and the Romanian Orthodox Cathedral". Europe-Asia Studies. 58 (7): 1119–1139. doi:10.1080/09668130600926447. ISSN 0966-8136. S2CID 143841394.

- Stan, Lavinia; Turcescu, Lucian (2007). Religion and Politics in Post-Communist Romania. USA: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530853-2.

- Țipău, Mihai (2004). Domnii fanarioți în Țările Române, 1711-1821: mică enciclopedie (in Romanian). Editura Omonia. ISBN 978-973-8319-17-2.

Further reading

[edit]External links

[edit]- Romanian Orthodox Church

- Eastern Orthodoxy by country

- Religious organizations established in 1872

- Members of the World Council of Churches

- Eastern Orthodox organizations established in the 19th century

- Christian denominations established in the 19th century

- 1872 establishments in Romania

- Culture of Romania

- Religious organizations based in Bucharest