Portraits of Periodical Offering

The Portraits of Periodical Offering (simplified Chinese: 职贡图; traditional Chinese: 職貢圖; pinyin: Zhígòngtú) were tributary documentative paintings (with illustration on each of the portrait) produced by various Chinese dynasties and later as well in other East Asian dynasties, such as Japan and Vietnam. These paintings were official historical documents by the imperial courts. The term "職貢圖" roughly translates to "duty offering pictorial". Throughout Chinese history, tributary states and tribes were required to send ambassadors to the imperial court periodically and pay tribute with valuable gifts (貢品; gòngpǐn).

Drawings and paintings with short descriptions were used to record the expression of these ambassadors and to a lesser extent to show the cultural aspects of these ethnic groups. These historical descriptions beside the portrait became the equivalent of documents of diplomatic relations with each country. The drawings were reproduced in woodblock printing after the 9th century and distributed among the bureaucracy in albums. The Portraits of Periodical Offering of Imperial Qing by Xie Sui (謝遂), completed in 1751, gives verbal descriptions of outlying tribes as far as the island of Britain in Western Europe.

Portraits of Periodical Offering of Liang (526–539 CE)

[edit]The Portraits of Periodical Offering of Liang (梁職貢圖) was painted by the future Emperor Yuan of Liang, Xiao Yi (ruled 552–555 CE) of the Liang dynasty while he was a Governor of the province of Jingzhou as a young man between 526 and 539 CE, a post he held again between 547 and 552 CE, and had the opportunity to meet many foreigners.[1][2][3] It is the earliest surviving of these specially significant paintings. They reflect foreign embassies that took place, particularly regarding the three Hephthalite (Hua) ambassadors, in 516–520 CE.[4][5] The original of the work was lost, but three copies or derived works are known.

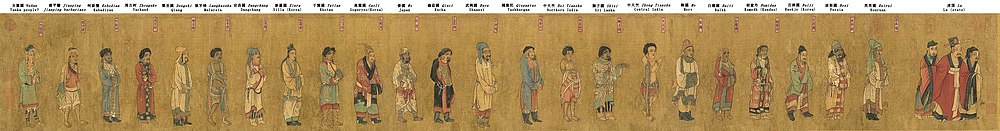

Portraits of Periodical Offering of Liang (526–539 CE) (Song dynasty copy of the 11th century CE)

[edit]A surviving edition of this work is a copy from the Song dynasty in the 11th century, the Song copy of the Portraits of Periodical Offering of Liang (梁職貢圖宋摹本),[6] and is currently preserved at the National Museum of China. The original work consisted of at least twenty five portraits of ambassadors from their various countries. The copy from the Song dynasty has twelve portraits and descriptions of thirteen envoys; the envoy from Dangchang has no portrait.[7] The work included individual descriptions, which follow closely the dynastic chronicle Liangshu (Volume 54).

The envoys from right to left were: the Hephthalites (滑/嚈哒), Persia (波斯), Korea (百濟), Kucha (龜茲), Japan (倭), Malaysia (狼牙脩), Qiang (鄧至), Yarkand (周古柯), Kabadiyan (呵跋檀), Kumedh (胡蜜丹), Balkh (白題), and finally Merv (末).[4][3][7]

The remaining countries, now lost, are thought to have been: Gaojuli 高句麗 (Goguryeo), Yutian 於闐 (Hotan in Xinjiang), Xinluo 新羅 (Silla), Kepantuo 渴盤陀 (Tashkurgan 塔什干 in present-day Xinjiang),[8] Wuxing fan 武興藩 (in Shanxi), Gaochang 高昌 (Turpan), Tianmen Man 天門蠻 (somewhere between Henan, Hubei, and Guizhou), Dan 蜑 Barbarians of Jianping 建平蠻 (between Hubei and Sichuan), and Man 蠻 Barbarians of Linjiang 臨江蠻 (East Sichuan). There may also have been: Zhongtianzhu 中天竺, Bei tianzhu 北天竺 (India), and Shiziguo 獅子國 (Sri Lanka), for a total of twenty-five countries.[3]

Individual portraits

[edit]Some of the main portraits are:

-

Hephthalite (滑 Hua) ambassador

-

Persian ambassador (波斯 Bosi)

-

Kucha ambassador (龜茲 Qiuci)

-

Kumedh ambassador (胡蜜丹 Humidan)

-

Kabadiyan ambassador (呵跋檀 Kebotan)

-

Langkasuka ambassador (狼牙脩 Lang-ga-siu) to the Southern Liang court 516-520 CE

Tang dynasty The Gathering of Kings (circa 650 CE)

[edit]A Tang period painting consisting in a version of the Liang portraits of Periodical Offerings, entitled The Gathering of Kings (王會圖, Wanghuitu).[9] It was probably made by Yan Liben.

From right to left, the countries are Lu (魯國) which is a reference to the Eastern Wei, Rouran (芮芮國), Persia (波斯國), Baekje (百濟國), Kumedh (胡密丹), Baiti (白題國), Merv (靺國), Central India (中天竺), Sri Lanka (獅子國), Northern India (北天竺), Tashkurgan (謁盤陀), Wuxing City of the Chouchi (武興國), Kucha (龜茲國), Japan (倭國), Goguryeo (高麗國), Khotan (于闐國), Silla (新羅國), Dangchang (宕昌國), Langkasuka (狼牙修), Dengzhi (鄧至國), Yarkand (周古柯), Kabadiyan (阿跋檀), Barbarians of Jianping (建平蠻), Nudan (女蜑國). See the complete Wanghuitu.

Individual portraits

[edit]Some of the main portraits are:

-

Man from Khotan (于闐國 Yutian) visiting the Chinese Tang dynasty court, in Wanghuitu circa 650 CE

-

Ambassador from Kucha (龜茲國 Qiuci-guo) at the Chinese Tang dynasty court. Wanghuitu (王会图), circa 650 CE

-

Ambassador from Tashkurgan (謁盤陀 Qiepantuo) Wanghuitu (王会图), circa 650 CE

-

Ambassador from Central India (中天竺 Zhong Tianzhu) to the court of the Tang dynasty. 王会图 circa 650 CE

Southern Tang Entrance of the Foreign Visitors (10th century CE)

[edit]Emperor Yuan of Liang, Xiao Yi (552-555 CE) made another painting entitled "Entrance of the Foreign Visitors" (番客入朝圖), now lost. A copy named "Entrance of the Foreign Visitors of Emperor Yuan of Liang" (梁元帝番客入朝圖) was made by the painter Gu Deqian (顧德謙) of the Southern Tang dynasty (937–976 CE), native of Jiangsu.[10]

From right to left, the countries are Lu (魯國) which is a reference to the Eastern Wei, Rouran (芮芮國), Tuyuhun (河南), Central India (中天竺), Western Wei (為國),[a] Champa (林邑國), Sri Lanka (師子國), Northern India (北天竺), Tashkurgan (渴盤陀國), Wuxing City of the Chouchi (武興蕃), Dangchang (宕昌國), Langkasuka (狼牙修), Dengzhi (鄧至國), Persia (波斯國), Baekje (百濟國), Kucha (龜茲國), Japan (倭國), Yarkand (周古柯), Kabadiyan (阿跋檀), Kumedh (胡密丹國), Baiti (白題國), Barbarians of Linjiang (臨江蠻), Goguryeo (高麗國), Gaochang (高昌國), Barbarians of Tianmen (天門蠻), Barbarians of Jianping (建平蠻), Hephthalites (滑國), Khotan (于闐), Silla (新羅國), Kantoli (干陀國), Funan (扶南國).

Portraits of Periodical Offering of Tang (Song dynasty copy, 11–13th century)

[edit]The Portraits of Periodical Offering of Tang by painter Yan Liben, depicting foreign envoys with tribute bearers for the Tang dynasty arriving at Chang'an in 631, during the reign of the Emperor Taizong of Tang. The painting consists of 27 people from various states. The original work was lost, and the only surviving edition was a Song dynasty copy, which is currently preserved at the National Palace Museum in Taipei.[12]

Portraits of Offerings to the Imperial Qing (1759)

[edit]In the mid-18th century during the Qing dynasty, the painter Xiesui (謝遂) again painted a Portraits of Periodical Offering of the Imperial Qing (Huángqīng Zhígòngtú 皇清職貢圖), completed in 1759, with a second part added in 1765, showing various foreign people known at that time, with texts in Chinese and Manchu. See the complete Huangqing Zhigongtu.

-

French man, 18th century

-

Man from Helvetia

-

Man from Hungary

-

Man from England

-

Vietnamese dignitaries of the late-Lê dynasty (1533–1789)

-

Siamese (Thai) State Official

Ten Thousand Nations Coming to Pay Tribute (1761)

[edit]

Ten Thousand Nations Coming to Pay Tribute (simplified Chinese: 万国来朝图; traditional Chinese: 萬國來朝圖; pinyin: Wànguó láicháo tú, 1761) is a monumental (299x207cm) Qing dynasty painting depicting foreign delegations visiting the Qianlong Emperor in the Forbidden city in Beijing during the late 1750s.[13]

The painting was intended to show the cosmopolitanism and the centrality of the Qing Empire, since most countries of Asia and Europe are shown paying their respects to the Chinese Emperor.[13][14] The title literally refers to ten thousand countries ("万国"), but this simply has the meaning of an uncountable multitude.

Related works

[edit]-

Tribute delegation of Liao dynasty "契丹國" to the Southern Song dynasty as depicted in the Periodical Offering Painting (職貢圖) by Ming dynasty artist Qiu Ying (仇英)

-

Popular multicolored New Year print (nianhua 年畫) entitled "Ten Thousand Countries Coming to Court" (Wanguo laichao tu 萬國來朝圖), by Wang Junfu 王君甫, mid to late 17th century.[15]

See also

[edit]- Foreign relations of imperial China

- Tributary system of China

- List of tributary states of China

- Twenty-Four Histories

- Chinese historiography

- Monarchy of China

- Pax Sinica

- Zongli Yamen

References

[edit]- ^ Yu, Taishan (Institute of History, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences) (January 2018). "The Illustration of Envoys Presenting Tribute at the Liang Court". Eurasian Studies. VI: 68–122.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zheng, Xinmiao (2017). Masterpieces of Classical Chinese Painting. Abbeville Press.

- ^ a b c Ge, Zhaoguang (Professor of History, Fudan University, China) (2019). "Imagining a Universal Empire: a Study of the Illustrations of the Tributary States of the Myriad Regions Attributed to Li Gonglin" (PDF). Journal of Chinese Humanities. 5: 128.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b DE LA VAISSIÈRE, ÉTIENNE (2003). "Is There a "Nationality of the Hephtalites"?". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 17: 127–128. ISSN 0890-4464. JSTOR 24049310.

- ^ DE LA VAISSIÈRE, ÉTIENNE (2003). "Is There a "Nationality of the Hephtalites"?". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 17: 130, note 31. ISSN 0890-4464. JSTOR 24049310.

- ^ Yu, Taishan (Institute of History, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences) (January 2018). "The Illustration of Envoys Presenting Tribute at the Liang Court". Eurasian Studies. VI: 93.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Lung, Rachel (2011). Interpreters in Early Imperial China. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 29, n.14, 99. ISBN 978-90-272-2444-6.

- ^ Equivalence between Kepantuo and Tashkurgan in page 436, location east of Congling (葱嶺 Pamir Mountains) and west of Zhujubo (朱駒波, Yarkand) in page 66 in Balogh, Dániel (12 March 2020). Hunnic Peoples in Central and South Asia: Sources for their Origin and History. Barkhuis. pp. 436, 66. ISBN 978-94-93194-01-4.

- ^ Zhou, Xiuqin (University of Pennsylvania) (April 2009). "Zhaoling: The Mausoleum of Emperor Tang Taizong" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. 187: 155.

- ^ "他的《番客人朝图》及《职贡图》至今在中国画史上占据重要的位置。" in Yi, Xuehua (2015). "江南天子皆词客——梁元帝萧绎之评价 – 百度文库". Journal of Huanche S&T University. 17: 83.

- ^ "邦国来朝:揭台北故宫藏职贡图题材的国家排序力秘密".

- ^ "Foreign Envoys with Tribute Bearers". National Palace Museum. Archived from the original on 16 September 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ a b c Liu, Xin (12 August 2022). Anglo-Chinese Encounters Before the Opium War: A Tale of Two Empires Over Two Centuries. Taylor & Francis. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-1-000-63756-4.

- ^ Wade, Geoff; Chin, James K. (19 December 2018). China and Southeast Asia: Historical Interactions. Routledge. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-429-95213-5.

- ^ Zhang, Qiong (26 May 2015). Making the New World Their Own: Chinese Encounters with Jesuit Science in the Age of Discovery. BRILL. pp. 352–353. ISBN 978-90-04-28438-8.

![Popular multicolored New Year print (nianhua 年畫) entitled "Ten Thousand Countries Coming to Court" (Wanguo laichao tu 萬國來朝圖), by Wang Junfu 王君甫, mid to late 17th century.[15]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/12/Popular_multicolored_New_Year_print_%28nianhua_%E5%B9%B4%E7%95%AB%29_entitled_%22Ten_Thousand_Countries_Coming_to_Court%22_%28Wanguo_laichao_tu_%E8%90%AC%E5%9C%8B%E4%BE%86%E6%9C%9D%E5%9C%96%29%2C_by_Wang_Junfu_%E7%8E%8B%E5%90%9B%E7%94%AB%2C_mid_to_late_17th_century.jpg/199px-thumbnail.jpg)