Bribery

Bribery is the offering, giving, receiving, or soliciting of any item of value to influence the actions of an official, or other person, in charge of a public or legal duty and to incline the individual to act contrary to their duty and the known rules of honesty and integrity.[1] With regard to governmental operations, essentially, bribery is "Corrupt solicitation, acceptance, or transfer of value in exchange for official action."[2]

Gifts of money or other items of value that are otherwise available to everyone on an equivalent basis, and not for dishonest purposes, are not bribery. Offering a discount or a refund to all purchasers is a legal rebate and is not bribery. For example, it is legal for an employee of a Public Utilities Commission involved in electric rate regulation to accept a rebate on electric service that reduces their cost of electricity, when the rebate is available to other residential electric customers. However, giving a discount specifically to that employee to influence them to look favorably on the electric utility's rate increase applications would be considered bribery.

A bribe is an illegal or unethical gift or lobbying effort bestowed to influence the recipient's conduct. It may be money, goods, rights in action, property, preferment, privilege, emolument, objects of value, advantage, or merely a promise to induce or influence the action, vote, or influence of a person in an official or public capacity.[3]

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 16 has a target to substantially reduce corruption and bribery of all forms as part of an international effort aimed at ensuring peace, justice, and strong institutions.[4]

Society often goes through changes that bring long-lasting positive or negative complications. Similar has been the case with bribery, which brought negative changes to societal norms as well as to trade. The researchers found that when bribery becomes part of social norms, one approach is not enough to tackle bribery due to the existence of different societies in different countries.[5][6] If severe punishment works in one country, it doesn't necessarily mean that severe punishment would work in another country to prevent bribery.[6] Also, the research found that bribery plays a significant role in public and private firms around the world.[7]

Forms

[edit]

Many types of payments or favors may be fairly or unfairly labeled as bribes: tip, gift, sop, perk, skim, favor, discount, waived fee/ticket, free food, free ad, free trip, free tickets, sweetheart deal, kickback/payback, funding, inflated sale of an object or property, lucrative contract, donation, campaign contribution, fundraiser, sponsorship/backing, higher paying job, stock options, secret commission, or promotion (rise of position/rank).

One must be careful of differing social and cultural norms when examining bribery. Expectations of when a monetary transaction is appropriate can differ from place to place. Political campaign contributions in the form of cash, for example, are considered criminal acts of bribery in some countries, while in the United States, provided they adhere to election law, are legal. Tipping, for example, is considered bribery in some societies, while in others the two concepts may not be interchangeable.

In some Spanish-speaking countries, bribes are referred to as "mordida" (literally, "bite"). In Arab countries, bribes may be called baksheesh (a tip, gift, or gratuity) or "shay" (literally, "tea"). French-speaking countries often use the expressions "dessous-de-table" ("under-the-table" commissions), "pot-de-vin" (literally, "wine-pot"), or "commission occulte" ("secret commission" or "kickback"). While the last two expressions contain inherently a negative connotation, the expression "dessous-de-table" can be often understood as a commonly accepted business practice. In German, the common term is Schmiergeld ("smoothing money").

The offence may be divided into two great classes: the one, where a person invested with power is induced by payment to use it unjustly; the other, where power is obtained by purchasing the suffrages of those who can impart it. Likewise, the briber might hold a powerful role and control the transaction; or in other cases, a bribe may be effectively extracted from the person paying it, although this is better known as extortion.

The forms that bribery take are numerous. For example, a motorist might bribe a police officer not to issue a ticket for speeding, a citizen seeking paperwork or utility line connections might bribe a functionary for faster service.

Bribery may also take the form of a secret commission, a profit made by an agent, in the course of his employment, without the knowledge of his principal. Euphemisms abound for this (commission, sweetener, kick-back etc.) Bribers and recipients of bribery are likewise numerous although bribers have one common denominator and that is the financial ability to bribe.

In 2007, bribery was thought to be worth around one trillion dollars worldwide.[8]

As indicated on the pages devoted to political corruption, efforts have been made in recent[when?] years by the international community to encourage countries to dissociate and incriminate as separate offences, active and passive bribery. From a legal point of view, active bribery can be defined for instance as the promising, offering or giving by any person, directly or indirectly, of any undue advantage [to any public official], for himself or herself or for anyone else, for him or her to act or refrain from acting in the exercise of his or her functions. (article 2 of the Criminal Law Convention on Corruption (ETS 173) of the Council of Europe). Passive bribery can be defined as the request or receipt [by any public official], directly or indirectly, of any undue advantage, for himself or herself or for anyone else, or the acceptance of an offer or a promise of such an advantage, to act or refrain from acting in the exercise of his or her functions (article 3 of the Criminal Law Convention on Corruption (ETS 173)).

The reason for this dissociation is to make the early steps (offering, promising, requesting an advantage) of a corrupt deal already an offence and, thus, to give a clear signal (from a criminal policy point of view) that bribery is not acceptable. Besides, such a dissociation makes the prosecution of bribery offences easier since it can be very difficult to prove that two parties (the bribe-giver and the bribe-taker) have formally agreed upon a corrupt deal. Besides, there is often no such formal deal but only a mutual understanding, for instance when it is common knowledge in a municipality that to obtain a building permit one has to pay a "fee" to the decision maker to obtain a favourable decision.

When examining the fact of bribe taking, we primarily need to understand that any action is affected by various elements; in addition, all these elements are interrelated. For instance, it would be wrong to indicate that the bribe-taker's motive is greediness as such, without examining causes of appearance of greediness in the personality of the particular bribe-taker. Largely, it is possible to confine oneself to the motive of greediness only in case if a bribe-taker tries to satisfy the primary (physical) needs. Yet, if money serves to satisfy secondary – psychological – needs, we should search for deeper motives of bribe taking.[9][10]

Government

[edit]

A grey area may exist when payments to smooth transactions are made. United States law is particularly strict in limiting the ability of businesses to pay for the awarding of contracts by foreign governments; however, the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act contains an exception for "grease payments"; very basically, this allows payments to officials in order to obtain the performance of ministerial acts which they are legally required to do, but may delay in the absence of such payment. In some countries, this practice is the norm, often resulting from a developing nation not having the tax structure to pay civil servants an adequate salary. Nevertheless, most economists regard bribery as a bad thing because it encourages rent seeking behaviour. A state where bribery has become a way of life is a kleptocracy.

Recent[when?] evidence suggests that the act of bribery can have political consequences- with citizens being asked for bribes becoming less likely to identify with their country, region and/or tribal unit.[11][12]

Tax treatment

[edit]The tax status of bribes is an issue for governments since the bribery of government officials impedes the democratic process and may interfere with good government. In some countries, such bribes are considered tax-deductible payments. However, in 1996, in an effort to discourage bribery, the OECD Council recommended that member countries cease to allow the tax-deductibility of bribes to foreign officials. This was followed by the signing of the Anti-Bribery Convention.[13] Since that time, the majority of the OECD countries which are signatories of the convention have revised their tax policies according to this recommendation and some have extended the measures to bribes paid to any official, sending the message that bribery will no longer be tolerated in the operations of the government.[14]

As any monetary benefit received from an illegal activity such as bribery is generally considered part of one's taxable income, however, as it is criminal, some governments may refuse to accept it as income as it may mean they are a party to the activity.[15]

Trade

[edit]According to researchers, bribery has a major impact on a country's trade system. The key findings suggest two possible outcomes when bribery becomes part of country's export system.[7] First, when firms and government officials are involved in bribery in the home country, the home country's export increases because incentives are gained through bribery.[7] Second, the home country's import decreases, because domestic firms lose interest in foreign markets, and minimize their import from other countries.[7] Also, in another study, it was found that firms are willing to risk paying higher bribes if the returns are high, even if it involves "risk and consequences of detection and punishment".[16] Additionally, other findings show that, in comparison to public firms, private firms pay most bribes abroad.[16]

Medicine

[edit]Pharmaceutical corporations may seek to entice doctors to favor prescribing their drugs over others of comparable effectiveness. If the medicine is prescribed heavily, they may seek to reward the individual through gifts.[17] The American Medical Association has published ethical guidelines for gifts from industry which include the tenet that physicians should not accept gifts if they are given in relation to the physician's prescribing practices.[18] Doubtful cases include grants for traveling to medical conventions that double as tourist trips.

Dentists often receive samples of home dental care products such as toothpaste, which are of negligible value; somewhat ironically, dentists in a television commercial will often state that they get these samples but pay to use the sponsor's product.

In countries offering state-subsidized or nationally funded healthcare where medical professionals are underpaid, patients may use bribery to solicit the standard expected level of medical care. For example, in many formerly Communist countries from what used to be the Eastern Bloc it may be customary to offer expensive gifts to doctors and nurses for the delivery of service at any level of medical care in the non-private health sector.[19][20]

Politics

[edit]

Politicians receive campaign contributions[21] and other payoffs from powerful corporations, organizations or individuals in return for making choices in the interests of those parties, or in anticipation of favorable policy, also referred to as lobbying. This is not illegal in the United States and forms a major part of campaign finance, though it is sometimes referred to as the money loop.[citation needed] However, in many European countries, a politician accepting money from a corporation whose activities fall under the sector they currently (or are campaigning to be elected to) regulate would be considered a criminal offence, for instance the "Cash-for-questions affair" and "Cash for Honours" in the United Kingdom.

A grey area in these democracies is the so-called "revolving door" in which politicians are offered highly-paid, often consultancy jobs upon their retirement from politics by the corporations they regulate while in office, in return for enacting legislation favourable to the corporation while they are in office, a conflict of interest. Convictions for this form of bribery are easier to obtain with hard evidence, a specific amount of money linked to a specific action by the recipient of the bribe. Such evidence is frequently obtained using undercover agents, since evidence of a quid pro quo relation can often be difficult to prove. See also influence peddling and political corruption.

Recent[when?] evidence suggests that demands for bribes can adversely impact citizen level of trust and engagement with the political process.

Business

[edit]

Employees, managers, or salespeople of a business may offer money or gifts to a potential client in exchange for business.

For example, in 2006, German prosecutors conducted a wide-ranging investigation of Siemens AG to determine if Siemens employees paid bribes in exchange for business.

In some cases where the system of law is not well-implemented, bribes may be a way for companies to continue their businesses. In the case, for example, custom officials may harass a certain firm or production plant, officially stating they are checking for irregularities, halting production or stalling other normal activities of a firm. The disruption may cause losses to the firm that exceed the amount of money to pay off the official. Bribing the officials is a common way to deal with this issue in countries where there exists no firm system of reporting these semi-illegal activities. A third party, known as a "white glove",[22] may be involved to act as a clean middleman.

Specialist consultancies have been set up to help multinational companies and small and medium enterprises with a commitment to anti-corruption to trade more ethically and benefit from compliance with the law.

Contracts based on or involving the payment or transfer of bribes ("corruption money", "secret commissions", "pots-de-vin", "kickbacks") are void.[23]

In 2012, The Economist noted:

Bribery would be less of a problem if it wasn't also a solid investment. A new paper by Raghavendra Rau of Cambridge University and Yan Leung Cheung and Aris Stouraitis of the Hong Kong Baptist University examines 166 high-profile cases of bribery since 1971, covering payments made in 52 countries by firms listed on 20 different stockmarkets. Bribery offered an average return of 10 to 11 times the value of the bung[a] paid out to win a contract, measured by the jump in stockmarket value when the contract was won. America's Department of Justice found similarly high returns in cases it has prosecuted.[25]

In addition, a survey conducted by auditing firm Ernst & Young in 2012 found that 15 percent of top financial executives are willing to pay bribes in order to keep or win business. Another 4 percent said they would be willing to misstate financial performance. This alarming indifference represents a huge risk to their business, given their responsibility.[26]

Sport corruption

[edit]Referees and scoring judges may be offered money, gifts, or other compensation to guarantee a specific outcome in an athletic or other sports competition. A well-known example of this manner of bribery in the sport would be the 2002 Olympic Winter Games figure skating scandal, where the French judge in the pairs competition voted for the Russian skaters in order to secure an advantage for the French skaters in the ice dancing competition.

Additionally, bribes may be offered by cities in order to secure athletic franchises, or even competitions, as happened with the 2002 Winter Olympics. It is common practice for cities to "bid" against each other with stadiums, tax benefits, and licensing deals.[27]

Prevention

[edit]The research suggests that government should introduce training programs for public officials to help public officials from falling into the trap of bribery.[28] Also, anti-bribery programs should be integrated into education programs.[28] In addition, government should promote good culture in public and private sectors. There should be "clear code of conducts and strong internal control systems" which would improve the overall public and private system.[28] Furthermore, the research suggests that private and public sectors at home and abroad must work together to limit corruption in home firms and foreign firms.[7] There will be greater transparency and less chances of bribery. Alongside, cross border monitoring should be enhanced to minimize bribery on international level.[16]

Legislation

[edit]The U.S. introduced the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) in 1977 to address bribery of foreign officials. FCPA criminalized the influencing of foreign officials by companies through rewards or payments. This legislation dominated international anti-corruption enforcement until around 2010 when other countries began introducing broader and more robust legislation, notably the United Kingdom Bribery Act 2010.[29][30] The International Organization for Standardization introduced an international anti-bribery management system standard in 2016.[31] In recent[when?] years, cooperation in enforcement action between countries has increased.[32]

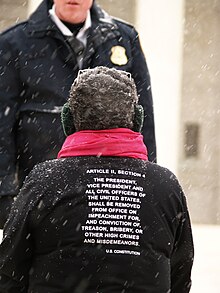

Under 18 U.S. Code § 201 – Bribery of public officials and witnesses, the law strictly prohibits any type of promising, giving, or offering of value to a public official. A public official is further defined as anyone who holds public or elected office.[33] Another stipulation of the law in place condemns the same kind of offering, giving, or coercing a witness in a legal case to changing their story.[33] Under the U.S Code § 1503, influencing or injuring officer or juror generally, it clearly states that any offense under the section means you can be imprisoned for the maximum of 10 years and/or fined.[34]

Businesses

[edit]Programs of prevention need to be properly designed and meet with international standards of best practice. To ensure respect for a program, whether it be on the part of employees or business partners, external verification is necessary. International best practices such as the Council for Further Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions, Annex 2;[26] the ISO 26000 norm (section 6.6.3) or TI Business Principles for Countering Bribery[35] are used in external verification processes to measure and ensure that a program of bribery prevention works and is consistent with international standards. Another reason for businesses to undergo external verification of their bribery prevention programs is that it means evidence can be provided to assert that all that was possible was done to prevent corruption. Companies are unable to guarantee corruption has never occurred; what they can do is provide evidence that they did their best to prevent it.

There is no federal statute under the U.S Law that prohibits or regulates any type of private or commercial bribery. There is a way for prosecutors to try people for bribery by using existing laws. Section 1346 of Title 18 can be used by prosecutors, to try people for 'a scheme or artifice to deprive another of the intangible right to honest services,' under the mail and wire fraud statutes.[36] Prosecutors have always successfully prosecuted private company employees for breaching a fiduciary duty and taking bribes, under Honest services fraud.

There are also cases of successful prosecution of bribery in the case of international business. The DOJ has used the Travel Act, 18 USC Section 1952 to prosecute bribery. Under the Travel Act, it is against the law, domestically and internationally, to utilize'the mail or any facility in interstate or foreign commerce' with intent to 'promote, manage, establish, carry on, or facilitate the promotion, management, establishment or carrying on, of any unlawful activity'.[36]

Notable instances

[edit]- Spiro Agnew, Republican, American Vice President who resigned from office in the aftermath of discovery that he took bribes while serving as Governor of Maryland.[37]

- John William Ashe, former President of the United Nations General Assembly (2013-2014) and key negotiator for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), was arrested 6 October 2015[38] and charged, along with five others, in a criminal complaint involving receiving bribes from Macau casino and real estate developer Ng Lap Seng.

- Pakistan cricket spot-fixing controversy, Mohammad Asif, Mohammad Amir and Salman Butt, Pakistani cricketers found guilty of accepting bribes to bowl no-balls against England at certain times.

- Duke Cunningham, United States Navy veteran and former Republican member of the United States House of Representatives from California's 50th Congressional District resigned after pleading guilty to accepting at least $2.4 million in bribes and under-reporting his income for 2004.[39]

- Gerald Garson, former New York Supreme Court Justice, convicted of accepting bribes to manipulate outcomes of divorce proceedings.

- Andrew J. Hinshaw, Republican, former congressman from California's 40th district, convicted of accepting bribes.

- John Jenrette, Democrat, former congressman from South Carolina's 6th district, convicted of accepting a bribe in the FBI's Abscam operation.

- Ralph Lauren, clothing retailer, was found guilty of making illegal payments and giving gifts to foreign officials in an attempt to circumvent customs inspections and paperwork.[40]

- Lee Myung-Bak, former South Korean president was found guilty of accepting nearly $6 million bribes from Samsung in exchange for a presidential pardon for Samsung Chairman Lee Kun-hee.[41]

- Donald "Buz" Lukens, Republican, former congressman from Ohio's 8th district, charged with delinquency of a minor and convicted of bribery and conspiracy.

- Martin Thomas Manton, former U.S. federal judge convicted of accepting bribes.

- Rick Renzi, Republican, former congressman from Arizona's 1st district, found guilty of 17 counts including wire fraud, conspiracy, extortion, racketeering, and money laundering.

- Tangentopoli (Italian for "city of bribes") was a huge bribery scandal in early 1990s Italy, which brought down the whole system of political parties, when it was uncovered by the Mani pulite investigations. At one point roughly half of members of parliament were under investigation.

- Dianne Wilkerson, Democrat, former Massachusetts state senator pleaded guilty to eight counts of attempted extortion.

- Larry Householder, Former speaker of the Ohio house was on the trial for his part in the biggest bribery scandal in Ohio history on 24 January 2023. Prosecutors accused him of taking $60m in bribes as corruption to pass a million-dollar bailout for Firstenergy [42]

Bribery in different countries

[edit]The research conducted in Papua New Guinea reflects cultural norms as the key reason for corruption. Bribery is a pervasive way of carrying out public services in PNG.[5] Papuans don't consider bribery as an illegal act, they considered bribery as a way of earning "quick money and sustain living".[5] Moreover, the key findings reflect that when corruption becomes a cultural norm, illegal acts such as bribery are not viewed as bad, and the clear boundaries that once distinguished between legal and illegal acts, and decisions are minimized on opinion, rather than on a code of conduct.[5][16]

The research conducted in Russia reflects that "bribery is a marginal social phenomenon" in the view of professional jurists and state employees.[6] The Russian law recognizes bribery as an official crime.[6] Consequently, legal platforms such as public courts are the only place where anti-bribery steps are taken in the country.[6] However, in reality, bribery cannot be addressed only by the "law-enforcement agencies and the courts".[6] Bribery needs to be addressed by informal social norms that set cultural values for the society. Also, the research suggests that the severity of punishment for bribery does very little to prevent people from accepting bribes in Russia.[6] Moreover, the research also revealed that a large number of Russians, approximately 70% to 77% have never given a bribe.[6] Nevertheless, if a need arises to pay a bribe for a problem, the research found that an overwhelming majority of Russians knew both what the sum of the bribe should be and how to deliver the bribe.[6] The Russian bribe problem reflects that unless there is an active change in all parts of society among both young and old, bribery will remain a major problem in Russian society, even when government officials label it as "marginal social phenomenon".[6]

For comparison amongst countries, Transparency International used to publish the Bribe Payers Index, but stopped in 2011.[43][44] Spokesperson Shubham Kaushik said the organisation "decided to discontinue the survey due to funding issues and to focus on issues that are more in line with our advocacy goals".[45]

Statistics

[edit]Following are the rates of reported bribery per 100,000 persons in last available year according to the United Nations. Comparisons between countries are difficult due to large differences in the fraction of unreported bribes.

| Country | Reported annual bribes per 100,000[46] |

Year |

|---|---|---|

| 17.4 | 2022 | |

| 0.2 | 2021 | |

| 0.0 | 2019 | |

| 0.0 | 2022 | |

| 11.5 | 2019 | |

| 1.7 | 2022 | |

| 1.8 | 2021 | |

| 0.0 | 2022 | |

| 0.0 | 2022 | |

| 19.4 | 2019 | |

| 0.6 | 2021 | |

| 0.7 | 2022 | |

| 2.5 | 2017 | |

| 0.0 | 2020 | |

| 0.0 | 2022 | |

| 2.8 | 2022 | |

| 1.5 | 2022 | |

| 0.7 | 2020 | |

| 0.7 | 2022 | |

| 1.3 | 2016 | |

| 0.9 | 2022 | |

| 1.8 | 2022 | |

| 8.5 | 2022 | |

| 1.8 | 2022 | |

| 1.7 | 2022 | |

| 0.2 | 2022 | |

| 0.6 | 2018 | |

| 0.0 | 2022 | |

| 0.4 | 2022 | |

| 0.0 | 2022 | |

| 8.1 | 2022 | |

| 0.0 | 2021 | |

| 0.4 | 2022 | |

| 0.4 | 2022 | |

| 1.9 | 2019 | |

| 5.9 | 2022 | |

| 1.3 | 2022 | |

| 0.0 | 2022 | |

| 3.3 | 2021 | |

| 0.0 | 2022 | |

| 0.1 | 2022 | |

| 8.2 | 2022 | |

| 0.0 | 2022 | |

| 0.7 | 2021 | |

| 0.8 | 2022 | |

| 0.6 | 2022 | |

| 0.0 | 2022 | |

| 0.9 | 2022 | |

| 6.5 | 2020 | |

| 0.1 | 2022 | |

| 1.9 | 2021 | |

| 1.8 | 2021 | |

| 8.3 | 2022 | |

| 0.1 | 2017 | |

| 0.0 | 2016 | |

| 12.3 | 2022 | |

| 0.0 | 2022 | |

| 0.0 | 2022 | |

| 2.1 | 2021 | |

| 1.3 | 2017 | |

| 0.9 | 2022 | |

| 0.5 | 2021 | |

| 1.7 | 2022 | |

| 0.3 | 2020 | |

| 2.7 | 2016 | |

| 3.6 | 2021 | |

| 1.9 | 2022 | |

| 54.4 | 2022 | |

| 0.0 | 2020 | |

| 1.3 | 2021 | |

| 0.0 | 2021 | |

| 0.8 | 2022 | |

| 0.0 | 2022 | |

| 0.2 | 2022 | |

| 2.3 | 2022 | |

| 0.3 | 2022 | |

| 0.4 | 2022 | |

| 0.0 | 2019 | |

| 7.7 | 2022 | |

| 0.5 | 2022 | |

| 0.1 | 2021 | |

| 2.2 | 2022 | |

| 11.0 | 2020 | |

| 0.0 | 2022 | |

| 0.0 | 2021 | |

| 5.1 | 2019 | |

| 0.1 | 2022 | |

| 2.0 | 2022 | |

| 10.6 | 2022 | |

| 1.2 | 2022 | |

| 9.0 | 2022 | |

| 0.3 | 2022 | |

| 0.0 | 2022 | |

| 1.6 | 2022 | |

| 0.7 | 2022 | |

| 0.0 | 2018 | |

| 0.0 | 2022 | |

| 3.7 | 2014 | |

| 1.2 | 2020 | |

| 0.7 | 2021 | |

| 0.2 | 2022 | |

| 0.4 | 2022 | |

| 0.6 | 2021 | |

| 0.0 | 2022 |

See also

[edit]- Ambitus

- Bid rigging

- Bribe Payers Index

- Charbonneau Commission

- Conflict of interest

- Consciousness of guilt

- Corruption by country

- Foreign Corrupt Practices Act

- Group of States Against Corruption (GRECO) of the Council of Europe

- Influence peddling

- ISO 37001 Anti-bribery management systems

- Jury tampering

- Kickback (bribery)

- Largitio

- Legal plunder

- Lobbying

- Match fixing

- Money trail – Money loop

- Organized crime

- Pay to Play

- Payola

- Point shaving

- Political corruption

- Price fixing

- Principal–agent problem

- Transparency International

- UK Bribery Act 2010

Footnotes

[edit]References

[edit]- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bribery". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ What is bribery?, Black's Law Dictionary, 4 November 2011, archived from the original on October 1, 2015, retrieved September 30, 2015

- ^ LII Staff (6 August 2007). "Bribery". LII / Legal Information Institute. Archived from the original on 8 March 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ See generally T. Markus Funk, "Don't Pay for the Misdeeds of Others: Intro to Avoiding Third-Party FCPA Liability," 6 BNA White Collar Crime Report 33 (January 13, 2011) Archived March 16, 2014, at the Wayback Machine (discussing bribery in the context of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act).

- ^ Doss, Eric. "Sustainable Development Goal 16". United Nations and the Rule of Law. Retrieved 2020-09-25.

- ^ a b c d Tiki, Samson; Luke, Belinda; Mack, Janet (October 2021). "Perceptions of bribery in Papua New Guinea's public sector: Agency and structural influences" (PDF). Public Administration and Development. 41 (4): 217–227. doi:10.1002/pad.1913. ISSN 0271-2075. S2CID 236221436.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Rimskii, Vladimir (2013-07-01). "Bribery as a Norm for Citizens Settling Problems in Government and Budget-Funded Organizations". Russian Politics and Law. 51 (4): 8–24. doi:10.2753/RUP1061-1940510401. ISSN 1061-1940. S2CID 197656271.

- ^ a b c d e Lee, Seung-Hyun; Weng, David H. (December 2013). "Does bribery in the home country promote or dampen firm exports?: Does Bribery Promote or Dampen Firm Exports?". Strategic Management Journal. 34 (12): 1472–1487. doi:10.1002/smj.2075.

- ^ "BBC NEWS – Business – African corruption 'on the wane'". bbc.co.uk. 10 July 2007. Archived from the original on 2009-04-22.

- ^ Krivins, A. (2018). "The motivational peculiarities of bribe-takers". SHS Web Conf. Volume 40, 2018 - 6th International Interdisciplinary Scientific Conference SOCIETY. HEALTH. WELFARE

- ^ Krivins, A. (2018). "The motivational peculiarities of bribe-takers". SHS Web of Conferences. 40: 01006. doi:10.1051/shsconf/20184001006.

- ^ Hamilton, A.; Hudson, J. (2014). "Bribery and Identity: Evidence from Sudan" (PDF). Bath Economic Research Papers, No 21/14. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-05-02.

- ^ Hamilton, A.; Hudson, J. (2014). "The Tribes that Bind: Attitudes to the Tribe and Tribal Leader in the Sudan" (PDF). Bath Economic Research Papers 31/14. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-02-06.

- ^ "OECD Anti Bribery Convention". Archived from the original on 2015-09-05.

- ^ "OECD Anti-corruption and integrity in the public sector". Archived from the original on 2018-03-05.

- ^ PinoyMoneyTalk (8 January 2007). "Income from scams and bribes are also taxable". pinoymoneytalk.com. Archived from the original on 14 February 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d Jeong, Yujin; Weiner, Robert J. (December 2012). "Who bribes? Evidence from the United Nations' oil-for-food program". Strategic Management Journal. 33 (12): 1363–1383. doi:10.1002/smj.1986. S2CID 54034648.

- ^ "Let the Sunshine in." The Economist Newspaper. Archived 2017-10-22 at the Wayback Machine Ecomomist.com (from Print Edition). 02 Mar. 2013. Retrieved 02 Dec. 2014.

- ^ "About the House of Delegates". ama-assn.org. 15 April 2018. Archived from the original on 16 April 2018.

- ^ Lewis, Mauree. (2000). Who is paying for healthcare in Eastern Europe and Central Asia? World Bank Publications.

- ^ Bribes for basic care in Romania Archived 2007-11-18 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian Weekly (March 26th 2008).

- ^ "OECD work on Money in Politics & Policy Capture". Archived from the original on 2018-03-14.

- ^ Wang Xiangwei, Corruption trials expose roles of the "white gloves" who manage the ill-gotten gains, South China Morning Post, published 9 September 2013, accessed 17 September 2023

- ^ International principle of law Trans-Lex.org Archived 2011-01-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "bung". Cambridge Dictionary. 7 February 2024. Retrieved 13 February 2024.

- ^ "You get who you pay for". The Economist. No. 2 June 2012. 2 June 2012. Archived from the original on 2 June 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ^ a b "OECD Anti-Bribery Convention". Archived from the original on 2015-09-05.

- ^ "OECD work on preventing corruption in sporting events and promoting responsible business conduct". Archived from the original on 2018-03-08.

- ^ a b c Nguyen, Thang V.; Doan, Minh H.; Tran, Nhung H. (December 2021). "The perpetuation of bribery–prone relationships: A study from Vietnamese public officials". Public Administration and Development. 41 (5): 244–256. doi:10.1002/pad.1961. ISSN 0271-2075. S2CID 239567859.

- ^ "Differences between the UK Bribery Act and the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act". Archived from the original on 2018-03-09. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- ^ Breslin, Brigid; Doron Ezickson; John Kocoras (2010). "The Bribery Act 2010: raising the bar above the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act". Company Lawyer. 31 (11). Sweet & Maxwell: 362. ISSN 0144-1027.

- ^ "New global framework for anti-bribery and corruption compliance programs Freshfields knowledge". knowledge.freshfields.com. Archived from the original on 2018-05-08. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- ^ "Anti-bribery and corruption: global enforcement and legislative developments 2017" (PDF). Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer. January 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-09-05. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ a b "18 U.S. Code § 201 - Bribery of public officials and witnesses".

- ^ "18 U.S. Code § 1503 - Influencing or injuring officer or juror generally". LII / Legal Information Institute.

- ^ "TI Business Principles for Countering Bribery. Available Online. Accessed on May 23, 2012" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 2, 2013. Retrieved 2013-04-20.

- ^ a b "United States – the Anti-Bribery and Anti-Corruption Review – Edition 6". The Law Reviews. Archived from the original on 2018-04-16. Retrieved 2018-04-15.

- ^ "Spiro T. Agnew, Point Man for Nixon Who Resigned Vice Presidency, Dies at 77". The New York Times. September 19, 1996.

- ^ Sengupta, Somini (June 23, 2016). "John Ashe, Ex-Diplomat Accused in U.N. Corruption Case, Dies at 61". The New York Times.

- ^ "House speaker says Cunningham faces 'serious consequences'". NC Times. Archived from the original on 2012-09-03.

- ^ "Ralph Lauren Corp. Agrees to Pay Fine in Bribery Case". The New York Times. April 22, 2013.

- ^ Jeong, Andrew (2018-04-09). "Former South Korean President Lee Indicted on Graft Charges". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2018-04-09.

- ^ Ariza, Mario (24 January 2023). "Prosecutors accuse Ohio Republicans of taking $60m in bribes as corruption trial opens". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ^ "Bribe Payers Index 2011 – Publications". Transparency.org. 2 November 2011. Retrieved 2023-03-03.

- ^ Pentland, William. "World's Most Bribery-Prone Businesses". Forbes. Retrieved 2023-03-03.

- ^ "Old Wall Street Journal report about corruption in Malaysia recirculates online". Fact Check. 2022-07-26. Retrieved 2023-03-03.

- ^ "United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Corruption & Economic Crime, Category "Corruption: Bribery"". Retrieved 17 August 2024.