Pride and Prejudice

Title page of the first edition, 1813 | |

| Author | Jane Austen |

|---|---|

| Working title | First Impressions |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Classic Regency novel Romance novel |

| Set in | Hertfordshire and Derbyshire |

| Publisher | T. Egerton, Whitehall |

Publication date | 28 January 1813 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (hardback, 3 volumes), digitalized |

| OCLC | 38659585 |

| 823.7 | |

| LC Class | PR4034 .P7 |

| Preceded by | Sense and Sensibility |

| Followed by | Mansfield Park |

| Text | Pride and Prejudice at Wikisource |

Pride and Prejudice is the second novel by English author Jane Austen, published in 1813. A novel of manners, it follows the character development of Elizabeth Bennet, the protagonist of the book, who learns about the repercussions of hasty judgments and comes to appreciate the difference between superficial goodness and actual goodness.

Mr Bennet, owner of the Longbourn estate in Hertfordshire, has five daughters, but his property is entailed and can only be passed to a male heir. His wife also lacks an inheritance, so his family faces becoming poor upon his death. Thus, it is imperative that at least one of the daughters marry well to support the others, which is a primary motivation driving the plot.

Pride and Prejudice has consistently appeared near the top of lists of "most-loved books" among literary scholars and the reading public. It has become one of the most popular novels in English literature, with over 20 million copies sold, and has inspired many derivatives in modern literature.[1][2] For more than a century, dramatic adaptations, reprints, unofficial sequels, films, and TV versions of Pride and Prejudice have portrayed the memorable characters and themes of the novel, reaching mass audiences.[3]

Plot summary

[edit]

In the early 19th century, the Bennet family live at their Longbourn estate, situated near the village of Meryton in Hertfordshire, England. Mrs Bennet's greatest desire is to marry off her five daughters to secure their futures.

The arrival of Mr Bingley, a rich bachelor who rents the neighbouring Netherfield estate, gives her hope that one of her daughters might contract a marriage to the advantage, because "It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife".

At a ball, the family is introduced to the Netherfield party, including Mr Bingley, his two sisters and Mr Darcy, his dearest friend. Mr Bingley's friendly and cheerful manner earns him popularity among the guests. He appears interested in Jane, the eldest Bennet daughter. Mr Darcy, reputed to be twice as wealthy as Mr Bingley, is haughty and aloof, causing a decided dislike of him. He declines to dance with Elizabeth, the second-eldest Bennet daughter, as she is "not handsome enough". Although she jokes about it with her friend, Elizabeth is deeply offended. Despite this first impression, Mr Darcy secretly begins to find himself drawn to Elizabeth as they continue to encounter each other at social events, appreciating her wit and frankness.

Mr Collins, the heir to the Longbourn estate, visits the Bennet family with the intention of finding a wife among the five girls under the advice of his patroness Lady Catherine de Bourgh, also revealed to be Mr Darcy's aunt. He decides to pursue Elizabeth. The Bennet family meet the charming army officer George Wickham, who tells Elizabeth in confidence about Mr Darcy's unpleasant treatment of him in the past. Elizabeth, blinded by her prejudice toward Mr Darcy, believes him.

Elizabeth dances with Mr Darcy at a ball, where Mrs Bennet hints loudly that she expects Jane and Bingley to become engaged. Elizabeth rejects Mr Collins' marriage proposal, to her mother's fury and her father's relief. Mr Collins subsequently proposes to Charlotte Lucas, a friend of Elizabeth, and is accepted.

Having heard Mrs Bennet's words at the ball and disapproving of the marriage, Mr Darcy joins Mr Bingley in a trip to London and, with the help of his sisters, persuades him not to return to Netherfield. A heartbroken Jane visits her Aunt and Uncle Gardiner in London to raise her spirits, while Elizabeth's hatred for Mr Darcy grows as she suspects he was responsible for Mr Bingley's departure.

In the spring, Elizabeth visits Charlotte and Mr Collins in Kent. Elizabeth and her hosts are invited to Rosings Park, Lady Catherine's home. Mr Darcy and his cousin, Colonel Fitzwilliam, are also visiting Rosings Park. Fitzwilliam tells Elizabeth how Mr Darcy recently saved a friend, presumably Bingley, from an undesirable match. Elizabeth realises that the prevented engagement was to Jane.

Mr Darcy proposes to Elizabeth, declaring his love for her despite her low social connections. She is shocked, as she was unaware of Mr Darcy's interest, and rejects him angrily, saying that he is the last person she would ever marry and that she could never love a man who caused her sister such unhappiness; she further accuses him of treating Wickham unjustly. Mr Darcy brags about his success in separating Bingley and Jane and sarcastically dismisses the accusation regarding Wickham without addressing it.

The next day, Mr Darcy gives Elizabeth a letter, explaining that Wickham, the son of his late father's steward, had refused the "living" his father had arranged for him and was instead given money for it. Wickham quickly squandered the money and tried to elope with Darcy's 15-year-old sister, Georgiana, for her considerable dowry. Mr Darcy also writes that he separated Jane and Bingley because he believed her to be indifferent to Bingley and because of the lack of propriety displayed by her family. Elizabeth is ashamed by her family's behaviour and her own prejudice against Mr Darcy.

Months later, Elizabeth accompanies the Gardiners on a tour of Derbyshire. They visit Pemberley, Darcy's estate. When Mr Darcy returns unexpectedly, he is exceedingly gracious with Elizabeth and the Gardiners. Elizabeth is surprised by Darcy's behaviour and grows fond of him, even coming to regret rejecting his proposal. She receives news that her sister Lydia has run off with Wickham. She tells Mr Darcy, then departs in haste. After an agonising interim, Wickham agrees to marry Lydia. Lydia and Wickham visit the Bennet family at Longbourn, where Lydia tells Elizabeth that Mr Darcy was at her wedding. Though Mr Darcy had sworn everyone involved to secrecy, Mrs Gardiner now feels obliged to inform Elizabeth that he secured the match, at great expense and trouble to himself.

Mr Bingley and Mr Darcy return to Netherfield. Jane accepts Mr Bingley's proposal. Lady Catherine, having heard rumours that Elizabeth intends to marry Mr Darcy, visits her and demands she promise never to accept Mr Darcy's proposal, as she and Darcy's late mother had already planned his marriage to her daughter Anne. Elizabeth refuses and asks the outraged Lady Catherine to leave. Darcy, heartened by his aunt's indignant relaying of Elizabeth's response, again proposes to her and is accepted.

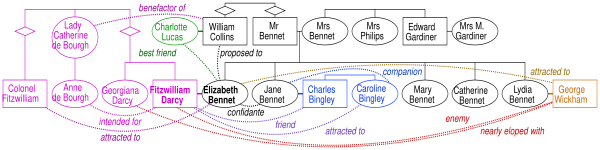

Characters

[edit]| Character genealogy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Elizabeth Bennet – the second-eldest of the Bennet daughters, she is attractive, witty and intelligent – but with a tendency to form tenacious and prejudiced first impressions. As the story progresses, so does her relationship with Mr Darcy. The course of Elizabeth and Darcy's relationship is ultimately decided when Darcy overcomes his pride, and Elizabeth overcomes her prejudice, leading them both to surrender to their love for each other.

- Mr Fitzwilliam Darcy – Mr Bingley's friend and the wealthy owner of the estate of Pemberley in Derbyshire, said to be worth at least £10,000 a year. Although he is handsome, tall, and intelligent, Darcy lacks ease and social graces, so others frequently mistake his initially haughty reserve as proof of excessive pride. A new visitor to the Meryton setting of the novel, he is ultimately Elizabeth Bennet's love interest. Though he appears to be proud and is largely disliked by people for this reason, his servants vouch for his kindness and decency.

- Mr Bennet – A logical and reasonable late-middle-aged landed gentleman of a more modest income of £2,000 per annum, and the dryly sarcastic patriarch of the Bennet family, with five unmarried daughters. His estate, Longbourn, is entailed to the male line. His affection for his wife wore off early in their marriage and is now reduced to mere toleration. He is often described as 'indolent' in the novel.

- Mrs Bennet (née Gardiner) – the middle-aged wife of Mr Bennet, and the mother of their five daughters. Mrs Bennet is a hypochondriac who imagines herself susceptible to attacks of tremors and palpitations (her "poor nerves") whenever things are not going her way. Her main ambition in life is to marry her daughters off to wealthy men. Whether or not any such matches will give her daughters happiness is of little concern to her. She was settled a dowry of £4,000 from her father.

- Jane Bennet – the eldest Bennet sister. She is considered the most beautiful young lady in the neighbourhood and is inclined to see only the good in others (but can be persuaded otherwise on sufficient evidence). She falls in love with Charles Bingley, a rich young gentleman recently moved to Hertfordshire and a close friend of Mr Darcy.

- Mary Bennet – the middle Bennet sister, and the plainest of her siblings. Mary has a serious disposition and mostly reads and plays music, although she is often impatient to display her accomplishments and is rather vain about them. She frequently moralises to her family. According to James Edward Austen-Leigh's A Memoir of Jane Austen, Mary ended up marrying one of her Uncle Philips' law clerks and moving into Meryton with him.

- Catherine "Kitty" Bennet – the fourth Bennet daughter. Though older than Lydia, she is her shadow and follows her in her pursuit of the officers of the militia. She is often portrayed as envious of Lydia and is described as a "silly" young woman. However, it is said that she improved when removed from Lydia's influence. According to James Edward Austen-Leigh's A Memoir of Jane Austen, Kitty later married a clergyman who lived near Pemberley.

- Lydia Bennet – the youngest Bennet sister. She is frivolous and headstrong. Her main activity in life is socialising, especially flirting with the officers of the militia. This leads to her running off with George Wickham, although he has no intention of marrying her. Lydia shows no regard for the moral code of her society; as Ashley Tauchert says, she "feels without reasoning".[5]

- Charles Bingley – a handsome, amiable, and wealthy young gentleman who leases Netherfield Park with hopes of purchasing it. Though generally well-mannered, he is easily influenced by his friend Mr Darcy and his sisters, which leads to the disruption of his romance with Jane Bennet. He inherited a fortune of £100,000.[6]

- Caroline Bingley – the snobbish sister of Charles Bingley, with a fortune of £20,000. She harbours designs on Mr Darcy and is jealous of his growing attachment to Elizabeth. She also disapproves of her brother's admiration for Jane Bennet and is disdainful of Meryton society, driven by her vanity and desire for social elevation.

- George Wickham – Wickham has been acquainted with Mr Darcy since infancy, being the son of Mr Darcy's father's steward. An officer in the militia, he is superficially charming and rapidly forms an attachment with Elizabeth Bennet. He later runs off with Lydia with no intention of marriage, which would have resulted in her and her family's complete disgrace, but for Darcy's intervention to bribe Wickham to marry her by paying off his immediate debts.

- Mr William Collins – Mr Collins is Mr Bennet's distant second cousin, a clergyman, and the current heir presumptive to his estate of Longbourn House. He is an obsequious and pompous man, prone to making long and tedious speeches, who is excessively devoted to his patroness, Lady Catherine de Bourgh.

- Lady Catherine de Bourgh – the overbearing aunt of Mr Darcy. Lady Catherine is the wealthy owner of Rosings Park, where she resides with her daughter Anne and is fawned upon by her rector, Mr Collins. She is haughty, pompous, domineering, and condescending and has long planned to marry off her sickly daughter to Darcy to 'unite their two great estates', claiming it to be the dearest wish of both her and her late sister, Lady Anne Darcy (née Fitzwilliam).

- Mr Edward Gardiner and Mrs Gardiner – Edward Gardiner is Mrs Bennet's brother and a successful tradesman of sensible and gentlemanly character. Aunt Gardiner is genteel and elegant and is close to her nieces Jane and Elizabeth. The Gardiners are the parents of four children. They are instrumental in bringing about the marriage between Darcy and Elizabeth.

- Georgiana Darcy – Georgiana is Mr Darcy's quiet, amiable and shy younger sister, with a dowry of £30,000, and is 16 when the story begins. When still 15, Miss Darcy almost eloped with Mr Wickham but was saved by her brother, whom she idolises. Thanks to years of tutelage under masters, she is accomplished at the piano, singing, playing the harp, drawing, and modern languages and is therefore described as Caroline Bingley's idea of an "accomplished woman".

- Charlotte Lucas – Elizabeth's 27-year-old friend. She marries Mr Collins for financial security, fearing becoming a burden to her family. Austen uses Charlotte's decision to illustrate how women of the time often married out of convenience rather than love, without condemning her choice.[7] Charlotte is the daughter of Sir William Lucas and Lady Lucas, neighbours of the Bennet family.

- Colonel Fitzwilliam – Colonel Fitzwilliam is the younger son of an earl and the nephew of Lady Catherine de Bourgh and Lady Anne Darcy; this makes him the cousin of Anne de Bourgh and the Darcy siblings, Fitzwilliam and Georgiana. He is about 30 years old at the beginning of the novel. He is the coguardian of Miss Georgiana Darcy, along with his cousin, Mr Darcy. According to Colonel Fitzwilliam, as a younger son, he cannot marry without thought to his prospective bride's dowry.

Major themes

[edit]Many critics take the title as the start when analysing the themes of Pride and Prejudice but Robert Fox cautions against reading too much into the title (which was initially First Impressions), because commercial factors may have played a role in its selection. "After the success of Sense and Sensibility, nothing would have seemed more natural than to bring out another novel of the same author using again the formula of antithesis and alliteration for the title."

The qualities of the title are not exclusively assigned to one or the other of the protagonists; both Elizabeth and Darcy display pride and prejudice."[8] The phrase "pride and prejudice" had been used over the preceding two centuries by Joseph Hall, Jeremy Taylor, Joseph Addison and Samuel Johnson.[9][10] Austen is thought to have taken her title from a passage in Fanny Burney's Cecilia (1782), a novel she is known to have admired:

"The whole of this unfortunate business," said Dr Lyster, "has been the result of PRIDE and PREJUDICE. ... if to PRIDE and PREJUDICE you owe your miseries, so wonderfully is good and evil balanced, that to PRIDE and PREJUDICE you will also owe their termination."[10][11] (capitalisation as in the original)

A theme in much of Austen's work is the importance of environment and upbringing in developing young people's character and morality.[12] Social standing and wealth are not necessarily advantages in her works, and a further theme common to Austen's work is ineffectual parents. In Pride and Prejudice, the failure of Mr and Mrs Bennet as parents is blamed for Lydia's lack of moral judgment. Darcy has been taught to be principled and scrupulously honourable but he is also proud and overbearing.[12] Kitty, rescued from Lydia's bad influence and spending more time with her older sisters after they marry, is said to improve greatly in their superior society.[13]

The American novelist Anna Quindlen observed in an introduction to an edition of Austen's novel in 1995:

Pride and Prejudice is also about that thing that all great novels consider, the search for self. And it is the first great novel that teaches us this search is as surely undertaken in the drawing room making small talk as in the pursuit of a great white whale or the public punishment of adultery.[14]

Marriage

[edit]The opening line of the novel announces: "It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife."[15] This sets marriage as a motif and a problem in the novel. Readers are poised to question whether or not these single men need a wife, or if the need is dictated by the "neighbourhood" families and their daughters who require a "good fortune".

Marriage is a complex social activity that takes political and financial economy into account. In the case of Charlotte Lucas, the seeming success of her marriage lies in the comfortable financial circumstances of their household, while the relationship between Mr and Mrs Bennet serves to illustrate bad marriages based on an initial attraction and surface over substance (economic and psychological).

The Bennets' marriage is an example that the youngest Bennet, Lydia, re-enacts with Wickham and the results are far from felicitous. Although the central characters, Elizabeth and Darcy, begin the novel as hostile acquaintances and unlikely friends, they eventually work toward a better understanding of themselves and each other, which frees them to truly fall in love. This does not eliminate the challenges of the real differences in their technically equivalent social status as gentry and their female relations. It does however provide them with a better understanding of each other's point of view from the different ends of the rather wide scale of differences within that category.

When Elizabeth rejects Darcy's first proposal, the argument of marrying for love is introduced. Elizabeth only accepts Darcy's proposal when she is certain she loves him and her feelings are reciprocated.[16] Austen's complex sketching of different marriages ultimately allows readers to question what forms of alliance are desirable especially when it comes to privileging economic, sexual, or companionate attraction.[17]

Wealth

[edit]Money plays a fundamental role in the marriage market, for the young ladies seeking a well-off husband and for men who wish to marry a woman of means. George Wickham tries to elope with Georgiana Darcy, and Colonel Fitzwilliam states that he will marry someone with wealth.

Marrying a woman of a rich family also ensured a linkage to a higher-class family, as is visible in the desires of Bingley's sisters to have their brother married to Georgiana Darcy. Mrs Bennet is frequently seen encouraging her daughters to marry a wealthy man of high social class. In chapter 1, when Mr Bingley arrives, she declares "I am thinking of his marrying one of them".[18]

Inheritance was by descent but could be further restricted by entailment, which in the case of the Longbourn estate restricted inheritance to male heirs only. In the case of the Bennet family, Mr Collins was to inherit the family estate upon Mr Bennet's death in the absence of any closer male heirs, and his proposal to Elizabeth would have ensured her security; but she refuses his offer.

Inheritance laws benefited males because married women did not have independent legal rights until the second half of the 19th century. For the upper-middle and aristocratic classes, marriage to a man with a reliable income was almost the only route to security for the woman and the children she was to have.[19] The irony of the opening line is that generally within this society it would be a woman who would be looking for a wealthy husband to have a prosperous life.[20]

Class

[edit]

Austen might be known now for her "romances" but the marriages in her novels engage with economics and class distinction. Pride and Prejudice is hardly the exception.

When Darcy proposes to Elizabeth, he cites their economic and social differences as an obstacle his excessive love has had to overcome, though he still anxiously harps on the problems it poses for him within his social circle. His aunt, Lady Catherine, later characterises these differences in particularly harsh terms when she conveys what Elizabeth's marriage to Darcy will become, "Will the shades of Pemberley be thus polluted?" Although Elizabeth responds to Lady Catherine's accusations that hers is a potentially contaminating economic and social position (Elizabeth even insists she and Darcy, as gentleman's daughter and gentleman, are "equals"), Lady Catherine refuses to accept the possibility of Darcy's marriage to Elizabeth. However, as the novel closes, "...through curiosity to see how his wife conducted herself", Lady Catherine condescends to visit them at Pemberley.[21]

The Bingleys present a particular problem for navigating class. Though Caroline Bingley and Mrs Hurst behave and speak of others as if they have always belonged in the upper echelons of society, Austen makes it clear that the Bingley fortunes stem from trade. The fact that Bingley rents Netherfield Hall – it is, after all, "to let" – distinguishes him significantly from Darcy, whose estate belonged to his father's family and who through his mother is the grandson and nephew of an earl. Bingley, unlike Darcy, does not own his property but has portable and growing wealth that makes him a good catch on the marriage market for poorer daughters of the gentry, like Jane Bennet, or of ambitious merchants. Class plays a central role in the evolution of the characters and Jane Austen's radical approach to class is seen as the plot unfolds.[22]

An undercurrent of the old Anglo-Norman upper class is hinted at in the story, as suggested by the names of Fitzwilliam Darcy and his aunt, Lady Catherine de Bourgh; Fitzwilliam, D'Arcy, de Bourgh (Burke), and even Bennet, are traditional Norman surnames.[23]

Self-knowledge

[edit]Through their interactions and their critiques of each other, Darcy and Elizabeth come to recognise their faults and work to correct them. Elizabeth meditates on her own mistakes thoroughly in chapter 36:

"How despicably have I acted!" she cried; "I, who have prided myself on my discernment! I, who have valued myself on my abilities! who have often disdained the generous candour of my sister, and gratified my vanity in useless or blameable distrust. How humiliating is this discovery! yet, how just a humiliation! Had I been in love, I could not have been more wretchedly blind. But vanity, not love, has been my folly. Pleased with the preference of one, and offended by the neglect of the other, on the very beginning of our acquaintance, I have courted prepossession and ignorance, and driven reason away, where either were concerned. Till this moment I never knew myself."[24]

Other characters rarely exhibit this depth of understanding or at least are not given the space within the novel for this sort of development.

Tanner writes that Mrs Bennet in particular, "has a very limited view of the requirements of that performance; lacking any introspective tendencies she is incapable of appreciating the feelings of others and is only aware of material objects".[25] Mrs Bennet's behaviour reflects the society in which she lives, as she knows that her daughters will not succeed if they do not get married. "The business of her life was to get her daughters married: its solace was visiting and news."[26] This shows that Mrs Bennet is only aware of "material objects" and not of her feelings and emotions.[27]

A notable exception is Charlotte Lucas, Elizabeth Bennet's close friend and confidant. She accepts Mr Collins's proposal of marriage once Lizzie rejects him, not out of sentiment but acute awareness of her circumstances as "one of a large family". Charlotte's decision is reflective of her prudent nature and awareness.

Style

[edit]Pride and Prejudice, like most of Austen's works, employs the narrative technique of free indirect speech, which has been defined as "the free representation of a character's speech, by which one means, not words actually spoken by a character, but the words that typify the character's thoughts, or the way the character would think or speak, if she thought or spoke".[28]

Austen creates her characters with fully developed personalities and unique voices. Though Darcy and Elizabeth are very alike, they are also considerably different.[29] By using narrative that adopts the tone and vocabulary of a particular character (in this case, Elizabeth), Austen invites the reader to follow events from Elizabeth's viewpoint, sharing her prejudices and misapprehensions. "The learning curve, while undergone by both protagonists, is disclosed to us solely through Elizabeth's point of view and her free indirect speech is essential ... for it is through it that we remain caught, if not stuck, within Elizabeth's misprisions."[28]

The few times the reader is allowed to gain further knowledge of another character's feelings, is through the letters exchanged in this novel. Darcy's first letter to Elizabeth is an example of this as through his letter, the reader and Elizabeth are both given knowledge of Wickham's true character.

Austen is known to use irony throughout the novel especially from viewpoint of the character of Elizabeth Bennet. She conveys the "oppressive rules of femininity that actually dominate her life and work, and are covered by her beautifully carved trojan horse of ironic distance."[5] Beginning with a historical investigation of the development of a particular literary form and then transitioning into empirical verifications, it reveals free indirect discourse as a tool that emerged over time as practical means for addressing the physical distinctness of minds. Seen in this way, free indirect discourse is a distinctly literary response to an environmental concern, providing a scientific justification that does not reduce literature to a mechanical extension of biology, but takes its value to be its own original form.[30]

Development of the novel

[edit]

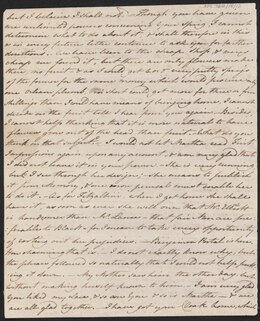

Austen began writing the novel after staying at Goodnestone Park in Kent with her brother Edward and his wife in 1796.[31] It was originally titled First Impressions, and was written between October 1796 and August 1797.[32] On 1 November 1797 Austen's father sent a letter to London bookseller Thomas Cadell to ask if he had any interest in seeing the manuscript, but the offer was declined by return post.[33]

The militia were mobilised after the French declaration of war on Britain in February 1793, and there was initially a lack of barracks for all the militia regiments, requiring the militia to set up huge camps in the countryside, which the novel refers to several times.[34]: 57 The Brighton camp for which the militia regiment leaves in May after spending the winter in Meryton was opened in August 1793, and the barracks for all the regiments of the militia were completed by 1796, placing the events of the novel between 1793 and 1795.[34]: 56–57

Austen made significant revisions to the manuscript for First Impressions between 1811 and 1812.[32] As nothing remains of the original manuscript, study of the first drafts of the novel is reduced to conjecture. From the large number of letters in the final novel, it is assumed that First Impressions was an epistolary novel.[35]

She later renamed the story Pride and Prejudice around 1811/1812, when she sold the rights to publish the manuscript to Thomas Egerton for £110[36] (equivalent to £9,300 in 2023). In renaming the novel, Austen probably had in mind the "sufferings and oppositions" summarised in the final chapter of Fanny Burney's Cecilia, called "Pride and Prejudice", where the phrase appears three times in block capitals.[12]

It is possible that the novel's original title was altered to avoid confusion with other works. In the years between the completion of First Impressions and its revision into Pride and Prejudice, two other works had been published under that name: a novel by Margaret Holford and a comedy by Horace Smith.[33]

Publication history

[edit]

Austen sold the copyright for the novel to Thomas Egerton from the Military Library, Whitehall in exchange for £110 (Austen had asked for £150).[37] This proved a costly decision. Austen had published Sense and Sensibility on a commission basis, whereby she indemnified the publisher against any losses and received any profits, less costs and the publisher's commission. Unaware that Sense and Sensibility would sell out its edition, making her £140,[33] she passed the copyright to Egerton for a one-off payment, meaning that all the risk (and all the profits) would be his. Jan Fergus has calculated that Egerton subsequently made around £450 from just the first two editions of the book.[38]

Egerton published the first edition of Pride and Prejudice in three hardcover volumes on 28 January 1813.[39] It was advertised in The Morning Chronicle, priced at 18s.[32] Favourable reviews saw this edition sold out, with a second edition published in October that year. A third edition was published in 1817.[37]

Foreign language translations first appeared in 1813 in French; subsequent translations were published in German, Danish, and Swedish.[40] Pride and Prejudice was first published in the United States in August 1832 as Elizabeth Bennet or, Pride and Prejudice.[37] The novel was also included in Richard Bentley's Standard Novel series in 1833. R. W. Chapman's scholarly edition of Pride and Prejudice, first published in 1923, has become the standard edition on which many modern published versions of the novel are based.[37]

The novel was originally published anonymously, as were all of Austen's novels. However, whereas her first published novel, Sense and Sensibility was presented as being written "by a Lady," Pride and Prejudice was attributed to "the Author of Sense and Sensibility". This began to consolidate a conception of Austen as an author, albeit anonymously. Her subsequent novels were similarly attributed to the anonymous author of all her then-published works.

Reception

[edit]19th century

[edit]The novel was well received, with three favourable reviews in the first months following publication.[38] Anne Isabella Milbanke, later to be the wife of Lord Byron, called it "the fashionable novel".[38] Noted critic and reviewer George Henry Lewes declared that he "would rather have written Pride and Prejudice, or Tom Jones, than any of the Waverley Novels".[41]

Throughout the 19th century, not all reviews of the work were positive. Charlotte Brontë, in a letter to Lewes, wrote that Pride and Prejudice was a disappointment, "a carefully fenced, highly cultivated garden, with neat borders and delicate flowers; but [...] no open country, no fresh air, no blue hill, no bonny beck".[41][42] Along with her, Mark Twain was overwhelmingly negative of the work. He stated, "Everytime I read Pride and Prejudice I want to dig [Austen] up and beat her over the skull with her own shin-bone."[43]

Austen for her part thought the "playfulness and epigrammaticism" of Pride and Prejudice was excessive, complaining in a letter to her sister Cassandra in 1813 that the novel lacked "shade" and should have had a chapter "of solemn specious nonsense, about something unconnected with the story; an essay on writing, a critique on Walter Scott or the history of Buonaparté".[44]

Walter Scott wrote in his journal, "Read again and for the third time at least, Miss Austen's very finely written novel of Pride and Prejudice."[45]

20th century

[edit]You could not shock her more than she shocks me,

Beside her Joyce seems innocent as grass.

It makes me most uncomfortable to see

An English spinster of the middle class

Describe the amorous effects of 'brass',

Reveal so frankly and with such sobriety

The economic basis of society.W. H. Auden (1937) on Austen[41]

The American scholar Claudia L. Johnson defended the novel from the criticism that it has an unrealistic fairy-tale quality.[46] One critic, Mary Poovey, wrote that the "romantic conclusion" of Pride and Prejudice is an attempt to hedge the conflict between the "individualistic perspective inherent in the bourgeois value system and the authoritarian hierarchy retained from traditional, paternalistic society".[46] Johnson wrote that Austen's view of a power structure capable of reformation was not an "escape" from conflict.[46] Johnson wrote the "outrageous unconventionality" of Elizabeth Bennet was in Austen's own time very daring, especially given the strict censorship that was imposed in Britain by the Prime Minister, William Pitt, in the 1790s when Austen wrote Pride and Prejudice.[46]

In the early twentieth century, the term "Collins," named for Austen's William Collins, came into use as slang for a thank-you note to a host.[47][48]

21st century

[edit]- In 2003 the BBC conducted a poll for the "UK's Best-Loved Book" in which Pride and Prejudice came second, behind The Lord of the Rings.[49]

- In a 2008 survey of more than 15,000 Australian readers, Pride and Prejudice came first in a list of the 101 best books ever written.[50]

- The 200th anniversary of Pride and Prejudice on 28 January 2013 was celebrated around the globe by media networks such as the Huffington Post, The New York Times, and The Daily Telegraph, among others.[51][52][53][54][55][56][57]

Adaptations

[edit]Film, television and theatre

[edit]Numerous screen adaptations have contributed in popularising Pride and Prejudice.[58]

The first television adaptation of the novel, written by Michael Barry, was produced in 1938 by the BBC. It is a lost television broadcast.[58] Some of the notable film versions include the 1940 Academy Award-winning film, starring Greer Garson and Laurence Olivier[59] (based in part on Helen Jerome's 1935 stage adaptation) and that of 2005, starring Keira Knightley (an Oscar-nominated performance) and Matthew Macfadyen.[60] Television versions include two by the BBC: a 1980 version starring Elizabeth Garvie and David Rintoul and a 1995 version, starring Jennifer Ehle and Colin Firth.

A stage version created by Helen Jerome premiered at the Music Box Theatre in New York in 1935, starring Adrianne Allen and Colin Keith-Johnston, and opened at the St James's Theatre in London in 1936, starring Celia Johnson and Hugh Williams. Elizabeth Refuses a play by Margaret Macnamara of scenes from the novel was made into a TV programme by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation in 1957.[61] First Impressions was a 1959 Broadway musical version starring Polly Bergen, Farley Granger, and Hermione Gingold.[62] In 1995, a musical concept album was written by Bernard J. Taylor, with Claire Moore in the role of Elizabeth Bennet and Peter Karrie in the role of Mr Darcy.[63] A new stage production, Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice, The New Musical, was presented in concert on 21 October 2008 in Rochester, New York, with Colin Donnell as Darcy.[64] The Swedish composer Daniel Nelson based his 2011 opera Stolthet och fördom on Pride and Prejudice.[65] Works inspired by the book include Bride and Prejudice and Trishna (1985 Hindi TV series).

The Lizzie Bennet Diaries – which premiered on a dedicated YouTube channel on 9 April 2012,[66] and concluded on 28 March 2013[67] – is an Emmy award-winning web-series[68] which recounts the story via vlogs recorded primarily by the Bennet sisters.[69][70] It was created by Hank Green and Bernie Su.[71]

In 2017, the bicentenary year of Austen's death, Pride and Prejudice – An adaptation in Words and Music to music by Carl Davis from the 1995 film and text by Gill Hornby was performed in the UK, with Hayley Mills as the narrator[72] This adaptation was presented in 2024 at the Sydney Opera House and the Arts Centre Melbourne, narrated by Nadine Garner.[73]

In 2018, part of the storyline of the Brazilian soap opera Orgulho e Paixão, aired on TV Globo, was inspired by the book. The soap opera was also inspired by other works of Jane Austen. It features actors, Nathalia Dill, Thiago Lacerda, Agatha Moreira, Rodrigo Simas, Gabriela Duarte, Marcelo Faria, Alessandra Negrini, and Natália do Vale.[74]

Fire Island is a movie written by Joel Kim Booster that reimagines Pride and Prejudice as a gay drama set on the quintessential gay vacation destination of Fire Island. Booster describes the movie "as an unapologetic and modern twist on Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice."[75] The movie was released in June 2022 and features a main cast of Asian-American actors.

Literature

[edit]The novel has inspired a number of other works that are not direct adaptations. Books inspired by Pride and Prejudice include the following:

- Mr Darcy's Daughters and The Exploits and Adventures of Miss Alethea Darcy by Elizabeth Aston

- Darcy's Story (a best seller) and Dialogue with Darcy by Janet Aylmer

- Pemberley: Or Pride and Prejudice Continued and An Unequal Marriage: Or Pride and Prejudice Twenty Years Later by Emma Tennant

- The Book of Ruth by Helen Baker

- Jane Austen Ruined My Life and Mr Darcy Broke My Heart by Beth Pattillo

- Precipitation – A Continuation of Miss Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice by Helen Baker

- Searching for Pemberley by Mary Simonsen

- Mr Darcy Takes a Wife and its sequel Darcy & Elizabeth: Nights and Days at Pemberley by Linda Berdoll

In Gwyn Cready's comedic romance novel, Seducing Mr Darcy, the heroine lands in Pride and Prejudice by way of magic massage, has a fling with Darcy and unknowingly changes the rest of the story.[76]

Abigail Reynolds is the author of seven Regency-set variations on Pride and Prejudice. Her Pemberley Variations series includes Mr Darcy's Obsession, To Conquer Mr Darcy, What Would Mr Darcy Do and Mr Fitzwilliam Darcy: The Last Man in the World. Her modern adaptation, The Man Who Loved Pride and Prejudice, is set on Cape Cod.[77]

Bella Breen is the author of nine variations on Pride and Prejudice. Pride and Prejudice and Poison, Four Months to Wed, Forced to Marry and The Rescue of Elizabeth Bennet.[78]

Helen Fielding's 1996 novel Bridget Jones's Diary is also based on Pride and Prejudice; the feature film of Fielding's work, released in 2001, stars Colin Firth, who had played Mr Darcy in the successful 1990s TV adaptation.

In March 2009, Seth Grahame-Smith's Pride and Prejudice and Zombies takes Austen's work and mashes it up with zombie hordes, cannibalism, ninja and ultraviolent mayhem.[79] In March 2010, Quirk Books published a prequel by Steve Hockensmith that deals with Elizabeth Bennet's early days as a zombie hunter, Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls.[80] The 2016 film of Grahame-Smith's adaptation was released starring Lily James, Sam Riley and Matt Smith.

In 2011, author Mitzi Szereto expanded on the novel in Pride and Prejudice: Hidden Lusts, a historical sex parody that parallels the original plot and writing style of Jane Austen.

Marvel has also published their take on this classic by releasing a short comic series of five issues that stays true to the original storyline. The first issue was published on 1 April 2009 and was written by Nancy Hajeski.[81] It was published as a graphic novel in 2010 with artwork by Hugo Petrus.

Pamela Aidan is the author of a trilogy of books telling the story of Pride and Prejudice from Mr Darcy's point of view: Fitzwilliam Darcy, Gentleman. The books are An Assembly Such as This,[82] Duty and Desire[83] and These Three Remain.[84]

Detective novel author P. D. James has written a book titled Death Comes to Pemberley, which is a murder mystery set six years after Elizabeth and Darcy's marriage.[85]

Sandra Lerner's sequel to Pride and Prejudice, Second Impressions, develops the story and imagined what might have happened to the original novel's characters. It is written in the style of Austen after extensive research into the period and language and published in 2011 under the pen name of Ava Farmer.[86]

Jo Baker's bestselling 2013 novel Longbourn imagines the lives of the servants of Pride and Prejudice.[87] A cinematic adaptation of Longbourn was due to start filming in late 2018, directed by Sharon Maguire, who also directed Bridget Jones's Diary and Bridget Jones's Baby, screenplay by Jessica Swale, produced by Random House Films and StudioCanal.[88] The novel was also adapted for radio, appearing on BBC Radio 4's Book at Bedtime, abridged by Sara Davies and read by Sophie Thompson. It was first broadcast in May 2014; and again on Radio 4 Extra in September 2018.[89]

In the novel Eligible, Curtis Sittenfeld sets the characters of Pride and Prejudice in modern-day Cincinnati, where the Bennet parents, erstwhile Cincinnati social climbers, have fallen on hard times. Elizabeth, a successful and independent New York journalist, and her single older sister Jane must intervene to salvage the family's financial situation and get their unemployed adult sisters to move out of the house and onward in life. In the process they encounter Chip Bingley, a young doctor and reluctant reality TV celebrity, and his medical school classmate, Fitzwilliam Darcy, a cynical neurosurgeon.[90][91]

Pride and Prejudice has also inspired works of scientific writing. In 2010, scientists named a pheromone identified in male mouse urine darcin,[92] after Mr Darcy, because it strongly attracted females. In 2016, a scientific paper published in the Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease speculated that Mrs Bennet may have been a carrier of a rare genetic disease, explaining why the Bennets didn't have any sons, and why some of the Bennet sisters are so silly.[93]

In summer 2014, Udon Entertainment's Manga Classics line published a manga adaptation of Pride and Prejudice.[94]

References

[edit]- ^ "Monstersandcritics.com". Monstersandcritics.com. 7 May 2009. Archived from the original on 26 October 2009. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ "Austen power: 200 years of Pride and Prejudice". The Independent. 19 January 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ^ Looser, Devoney (2017). The Making of Jane Austen. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-1421422824.

- ^ Janet M. Todd (2005), Books.Google.com, Jane Austen in Context, Cambridge University Press p. 127

- ^ a b Tauchert, Ashley (2003). "Mary Wollstonecraft and Jane Austen: 'Rape' and 'Love' as (Feminist) Social Realism and Romance". Women. 14 (2): 144. doi:10.1080/09574040310107. S2CID 170233564.

- ^ Austen, Jane (5 August 2010). Pride and Prejudice. Oxford University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-19-278986-0.

- ^ Rothman, Joshua (7 February 2013). "On Charlotte Lucas's Choice". The New Yorker. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ Fox, Robert C. (September 1962). "Elizabeth Bennet: Prejudice or Vanity?". Nineteenth-Century Fiction. 17 (2): 185–187. doi:10.2307/2932520. JSTOR 2932520.

- ^ "pride, n.1". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ a b Dexter, Gary (10 August 2008). "How Pride And Prejudice got its name". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ Burney, Fanny (1782). Cecilia: Or, Memoirs of an Heiress. T. Payne and son and T. Cadell. pp. 379–380.

- ^ a b c Pinion, F B (1973). A Jane Austen. Companion. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-12489-5.

- ^ Austen, Jane. Pride and Prejudice, Ch 61.

- ^ Quindlen, Anna (1995). Introduction. Pride and Prejudice. By Austen, Jane. New York: Modern Library. p. vii. ISBN 978-0-679-60168-5.

- ^ Austen, Jane. Pride and Prejudice, Ch 1.

- ^ Gao, Haiyan (February 2013). "Jane Austen's Ideal Man in Pride and Prejudice". Theory and Practice in Language Studies. 3 (2): 384–388. doi:10.4304/tpls.3.2.384-388.

- ^ Schmidt, Katrin (2004). The role of marriage in Jane Austen's 'Pride and Prejudice' (thesis). University of Münster. ISBN 9783638849210.

compare the different kinds of marriages described in the novel

- ^ Austen, Jane (1813). Pride and Prejudice. p. 3.

- ^ Chung, Ching-Yi (July 2013). "Gender and class oppression in Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice". IRWLE. 9 (2).

- ^ Bhattacharyya, Jibesh (2005). "A critical analysis of the novel". Jane Austen's Pride and prejudice. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. p. 19. ISBN 9788126905492.

The irony of the opening sentence is revealed when we find Mrs Bennett needs a single man with a good fortune....for...any one of her five single daughters

- ^ Pride and Pejudice. Vol. 3 (1813 ed.). pp. 322–323.

- ^ Michie, Elsie B. "Social Distinction in Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice, 1813, edited by Donald Gray and Mary A. Favret, fourth Norton critical edition (2016). pp. 370–381.

- ^ Doody, Margaret (14 April 2015). Jane Austen's Names: Riddles, Persons, Places. University of Chicago Press. p. 72. ISBN 9780226196022. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ Austen, Jane. "36". Pride and Prejudice.

- ^ Tanner, Tony (1986). Knowledge and Opinion: Pride and Prejudice. Macmillan Education Ltd. p. 124. ISBN 978-0333323175.

- ^ Austen, Jane (2016). Pride and Prejudice. W.W. Norton & Company Inc. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-393-26488-3.

- ^ Tanner, Tony (1986). Knowledge and Opinion: Pride and Prejudice. Macmillan Education Ltd. p. 124. ISBN 978-0333323175.

- ^ a b Miles, Robert (2003). Jane Austen. Writers and Their Work. Tavistock: Northcote House in association with the British Council. ISBN 978-0-7463-0876-9.

- ^ Baker, Amy. "Caught in the Act Of Greatness: Jane Austen's Characterization Of Elizabeth And Darcy By Sentence Structure In Pride and Prejudice." Explicator 72.3 (2014): 169–178. Academic Search Complete. Web. 16 February 2016.

- ^ Fletcher, Angus; Benveniste, Mike (Winter 2013). "A Scientific Justification for Literature: Jane Austen's Free Indirect Style as Ethical Tool". Journal of Narrative Theory. 43 (1): 13. doi:10.1353/jnt.2013.0011. S2CID 143290360.

- ^ "History of Goodnestone". Goodnestone Park Gardens. Archived from the original on 17 February 2010. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ^ a b c Le Faye, Deidre (2002). Jane Austen: The World of Her Novels. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-3285-2.

- ^ a b c Rogers, Pat, ed. (2006). The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Jane Austen: Pride and Prejudice. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82514-6.

- ^ a b Irvine, Robert (2005). Jane Austen. London: Routledge.

- ^ This theory is defended in "Character and Caricature in Jane Austen" by DW Harding in Critical Essays on Jane Austen (BC Southam Edition, London 1968) and Brian Southam in Southam, B.C. (2001). Jane Austen's literary manuscripts: a study of the novelist's development through the surviving papers (New ed.). London: the Athlone press / Continuum. pp. 58–59. ISBN 9780826490704.

- ^ Irvine, Robert (2005). Jane Austen. London: Routledge. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-415-31435-0.

- ^ a b c d Stafford, Fiona (2004). "Notes on the Text". Pride and Prejudice. Oxford World's Classics (ed. James Kinley). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280238-5.

- ^ a b c Fergus, Jan (1997). "The professional woman writer". In Copeland, E.; McMaster, J. (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Jane Austen. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-49867-8.

- ^ Howse, Christopher (28 December 2012). "Anniversaries of 2013". Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 31 December 2012.

- ^ Cossy, Valérie; Saglia, Diego (2005). "Translations". In Todd, Janet (ed.). Jane Austen in Context. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82644-0.

- ^ a b c Southam, B.C., ed. (1995). Jane Austen: The Critical Heritage. Vol. 1. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-13456-9.

- ^ Barker, Juliet R. V. (2016). The Brontës: A Life in Letters (2016 ed.). London: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-1408708316. OCLC 926822509.

- ^ "'Pride and Prejudice': What critics said". Jane Austen Summer Program. 3 October 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ Johnson, Claudia L. (1988). Jane Austen: Women, Politics, and the Novel. University of Chicago Press. p. 73. ISBN 9780226401393.

- ^ Scott, Walter (1998). The journal of Sir Walter Scott. Anderson, W.E.K. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 0862418283. OCLC 40905767.

- ^ a b c d Johnson (1988) p.74

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “Collins (n.2),” July 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/1085984454

- ^ Burrill, Katharine (27 August 1904). "Talks with Girls: Letter-Writing and Some Letter-Writers". Chambers's Journal. 7 (352): 611.

- ^ "BBC – The Big Read – Top 100 Books". May 2003. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- ^ "Aussie readers vote Pride and Prejudice best book". thewest.com.au. Archived from the original on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 24 February 2008.

- ^ "200th Anniversary of Pride And Prejudice: A HuffPost Books Austenganza". The Huffington Post. 28 January 2013.

- ^ Schuessler, Jennifer (28 January 2013). "Austen Fans to Celebrate 200 Years of Pride and Prejudice". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- ^ "Video: Jane Austen celebrated on 200th anniversary of Pride and Prejudice publication". Telegraph.co.uk. 28 January 2013. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013.

- ^ ABC News. "'Pride and Prejudice' 200th Anniversary". ABC News.

- ^ "Queensbridge Publishing: Pride and Prejudice 200th Anniversary Edition by Jane Austen". queensbridgepublishing.com.

- ^ Kate Torgovnick May (28 January 2013). "Talks to celebrate the 200th anniversary of Pride and Prejudice". TED Blog.

- ^ Rothman, Lily (28 January 2013). "Happy 200th Birthday, Pride & Prejudice...and Happy Sundance, Too: The writer/director of the Sundance hit 'Austenland' talks to TIME about why we still love Mr Darcy centuries years later". Time. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- ^ a b Fullerton, Susannah (2013). Happily Ever After: Celebrating Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice. Frances Lincoln Publishers. ISBN 978-0711233744. OCLC 1310745594.

- ^ Pride and Prejudice (1940) at IMDb

- ^ Pride and Prejudice (2005) at IMDb

- ^ "Elizabeth refuses". A.B.C. Weekly. 2 February 1957. p. 31. Retrieved 1 August 2024 – via Trove.

- ^ "First Impressions the Broadway Musical". Janeaustensworld.wordpress.com. 6 November 2008. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ "Pride and Prejudice (1995)". Bernardjtaylor.com. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ "PRIDE AND PREJUDICE, the Musical". prideandprejudice-themusical.com.

- ^ Stolthet och fördom / Pride and Prejudice (2011) Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, work details

- ^ "Episode 1: My Name is Lizzie Bennet". The Lizzie Bennet Diaries. Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ "Episode 100: The End". The Lizzie Bennet Diaries. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ "'Top Chef's' 'Last Chance Kitchen,' 'Oprah's Lifeclass,' the Nick App, and 'The Lizzie Bennet Diaries' to Receive Interactive Media Emmys". yahoo.com. 22 August 2013.

- ^ Hasan, Heba (24 April 2012). "Pride and Prejudice, the Web Diary Edition". Time. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- ^ Koski, Genevieve (3 May 2012). "Remember Pride And Prejudice? It's back, in vlog form!". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- ^ Matheson, Whitney (4 May 2012). "Cute Web series: 'The Lizzie Bennet Diaries'". USA Today. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- ^ "Oscar winner takes us through a glass, Darcy". Henley Standard. 11 September 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- ^ Jo Litson (16 August 2024). "Pride and Prejudice (Spiritworks & Theatre Tours International)". Limelight (review). Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- ^ "'Orgulho e Paixão': novela se inspira em livros de Jane Austen". Revista Galileu (in Brazilian Portuguese). 29 August 2022. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ Booster, Joel Kim. "Pride and Prejudice on Fire Island". Penguin Random House. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ Gómez-Galisteo, M. Carmen (2018). A Successful Novel Must Be in Want of a Sequel: Second Takes on Classics from The Scarlet Letter to Rebecca. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-1476672823.

- ^ "Abigail Reynolds Author Page". Amazon. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ "Bella Breen Author Page". Amazon.

- ^ Grossman, Lev (April 2009). "Pride and Prejudice, Now with Zombies". TIME. Archived from the original on 4 April 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2009.

- ^ "Quirkclassics.com". Quirkclassics.com. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ "Marvel.com". Marvel.com. Archived from the original on 24 July 2010. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ Aidan, Pamela (2006). An Assembly Such as This. Touchstone. ISBN 978-0-7432-9134-7.

- ^ Aidan, Pamela (2004). Duty and Desire. Wytherngate Press. ISBN 978-0-9728529-1-3.

- ^ Aidan, Pamela (2007). These Three Remain. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-9137-8.

- ^ Hislop, Victoria. Death Comes to Pemberley: Amazon.co.uk: Baroness P. D. James: 9780571283576: Books. ASIN 0571283578.

- ^ Farmer, Ava (2011). Second Impressions. Chawton, Hampshire, England: Chawton House Press. ISBN 978-1613647509.

- ^ Baker, Jo (8 October 2013). Longbourn. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0385351232.

- ^ "New direction for 'literary chameleon' Jo Baker to Transworld – The Bookseller". www.thebookseller.com.

- ^ "Jo Baker – Longbourn, Book at Bedtime – BBC Radio 4". BBC.

- ^ Sittenfeld, Curtis (19 April 2016). Eligible. Random House. ISBN 978-1400068326.

- ^ Gomez-Galisteo, Carmen (October 2022). "An Eligible Bachelor: Austen, Love, and Marriage in Pride and Prejudice and Eligible by Curtis Sittenfeld". Anglo Saxonica. 20 (1, art. 9). doi:10.5334/as.92. ISSN 0873-0628.

- ^ Roberts, Sarah A.; Simpson, Deborah M.; Armstrong, Stuart D.; Davidson, Amanda J.; Robertson, Duncan H.; McLean, Lynn; Beynon, Robert J.; Hurst, Jane L. (1 January 2010). "Darcin: a male pheromone that stimulates female memory and sexual attraction to an individual male's odour". BMC Biology. 8: 75. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-8-75. ISSN 1741-7007. PMC 2890510. PMID 20525243.

- ^ Stern, William (1 March 2016). "Pride and protein". Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 39 (2): 321–324. doi:10.1007/s10545-015-9908-7. ISSN 1573-2665. PMID 26743057. S2CID 24476197.

- ^ Manga Classics: Pride and Prejudice (2014) UDON Entertainment ISBN 978-1927925188

External links

[edit] Media related to Pride and Prejudice at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pride and Prejudice at Wikimedia Commons- Pride and Prejudice at Standard Ebooks

- Pride and Prejudice (Chapman edition) at Project Gutenberg

Pride and Prejudice public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Pride and Prejudice public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Digital resources relating to Jane Austen Archived 4 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine from the British Library's Discovering Literature website