Georgian Dublin

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2010) |

Georgian Dublin is a phrase used in terms of the history of Dublin that has two interwoven meanings:

- to describe a historic period in the development of the city of Dublin, Ireland, from 1714 (the beginning of the reign of King George I of Great Britain and of Ireland) to the death in 1830 of King George IV. During this period, the reign of the four Georges, hence the word Georgian, covers a particular and unified style, derived from Palladian Architecture, which was used in erecting public and private buildings

- to describe the modern day surviving buildings in Dublin erected in that period and which share that architectural style

Though, strictly speaking, Georgian architecture could only exist during the reigns of the four Georges, it had its antecedents prior to 1714 and its style of building continued to be erected after 1830, until replaced by later styles named after the then monarch, Queen Victoria, i.e. Victorian.

Dublin's development

[edit]Dublin was for much of its existence a medieval city, marked by the existence of a particular style of buildings, built on narrow winding medieval streets. The first major changes to this pattern occurred during the reign of King Charles II when the then Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, the Earl of Ormonde (later made Duke of Ormonde) issued an instruction which was to have dramatic repercussions for the city as it exists today. Though the city over the century had grown around the River Liffey, as in many other medieval cities, buildings backed onto the river. This allowed the dumping of household waste directly into the river, creating a form of collective sewer. As Dublin's quays underwent development, Ormonde insisted that the frontages of the houses, not their rears, should face the quay sides, with a street to run along each quay. By this single regulation Ormonde changed the face of the city. No longer would the river be a sewer hidden between buildings. Instead it became a central feature of the city, with its quays lined by large three and four-storey houses and classic public buildings, such as the Four Courts, the Custom House (1707) and, later and grander, Custom House designed, as was the Four Courts, by master architect James Gandon. For his initiative, Ormonde's name is now given to one of the city quays.

It was, however, only one of a number of crucial developments. As the city grew in size, stature, population and wealth, two changes were needed. (1) The existing narrow street medieval city required major redevelopment, and (2) major new development of residential areas was required.

Rebuilding Dublin's core

[edit]

A ceiling from the Dublin townhouse of Viscount Powerscourt, showing the splendour of Georgian decoration. His former townhouse was sensitively turned into a shopping centre in the 1980s.

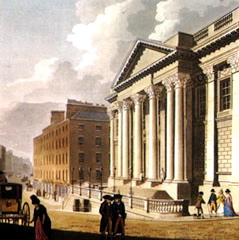

A new body called the Wide Streets Commission was created to remodel the old medieval city. It created a network of main thoroughfares by wholesale demolition or widening of old streets or the creation of entirely new ones. On the north side of the city, a series of narrow streets were merged and widened enormously to create a new street, called Sackville Street (now called O'Connell Street). At its lower end, a new bridge (now called O'Connell Bridge) was erected, beyond which two new streets in the form of a 'V' appeared, known as Westmoreland Street and D'Olier Street. Westmoreland Street in turn led to a renamed Hoggen Green, which became College Green because it faced unto Trinity College Dublin. The new Irish Houses of Parliament, designed by Edward Lovett Pearce, also faced onto College Green, while from College Green a new widened Dame Street led directly down to the medieval Christchurch Cathedral, Dublin, past Dublin Castle and the Royal Exchange, the latter a new building. The Castle began the process of rebuilding, turning it from a medieval castle to a Georgian palace.

Contemporary impressions

[edit]In 1764, John Bush, an English traveller, visited Dublin and had the following to say about the city:

- "Dublin is a large, populous, and, for the greater part of it, well built city; not much ornamented, indeed, with grand or magnificent buildings, a few, however, there are, of which the college or university, the only one they have in the kingdom - the parliament houses - the king's and the lying-in hospital, and Swift's for lunatics - with the marquis of Kildare's house are the principal. Their churches in general make but a very indifferent figure as to their architecture; and, what I was very much surprised at, are amazingly destitute of monumental ornament. The two houses of parliament are infinitely superior, in point of grandeur and magnificence, to those of Westminster. The house of lords is, perhaps, as elegant a room as any in Great-Britain or Ireland [..] The whole extent of the city of Dublin may be about one-third of London, including Westminster and Southwark, and one-fourth, at least, of the whole, from the accounts we received, has been built within these 40 years. Those parts of the town which have been added since that time are well built, and the streets in general well laid out, especially on the north side of the river; where the most considerable additions have been made within the term above mentioned." [1]

18th-century property developers

[edit]While the rebuilding by the Wide Streets Commission fundamentally changed the streetscape in Dublin, a property boom led to additional building outside the central core. Unlike twentieth century building booms in Dublin the eighteenth century developments were carefully controlled. The developing areas were divided into precincts, each of which was given to a different developer. The scope of their developments were restricted, however, with strict controls imposed on style of residential building, design of buildings and location, so producing a cohesive unity that came to be called Georgian Dublin.

Initially developments were focused on the city's north side. Among the earliest developments was Henrietta Street, a wide street lined on both sides by massive Georgian houses built on a palatial scale. At the top end of the street, a new James Gandon building, the King's Inns, was erected between 1795 and 1816. In this building, barristers were (and continue to be) trained and earned their academic qualifications.[2] Such was the prestige of the street that many of the most senior figures in Irish 'establishment' society, peers of the realm, judges, barristers, bishops bought houses here. Under the anti-Catholic Penal Laws, Roman Catholics, though the overwhelming majority in Ireland, were harshly discriminated against, barred from holding property rights or from voting in parliamentary elections until 1793. Thus the houses of Georgian Dublin, particularly in the early phase before Catholic Emancipation was granted in 1829, were almost invariably owned by a small Church of Ireland Anglican elite, with Catholics only gaining admittance to the houses as skivvies and servants. Ultimately the north side was laid out centred on two major squares, Rutland Square (now called Parnell Square for Charles Stewart Parnell), at the top end of Sackville Street, and Mountjoy Square. Such was the prestige of the latter square that among its many prominent residents was the Church of Ireland Archbishop of Dublin. Many of the streets in the new areas were named after the property developers, often with developers commemorated both in their name and by their peerage should they have received one. Among the streets named after developers are Capel Street, Mountjoy Square and Aungier Street.

For the initial years of the Georgian era, the north side of the city was considered a far more respectable area to live. However, when the Earl of Kildare chose to move to a new large ducal palace built for him on what up to that point was seen as the inferior southside, he caused shock. When his Dublin townhouse, Kildare House (renamed Leinster House when he was made Duke of Leinster) was finished, it was by far the biggest aristocratic residence other than Dublin Castle, and it was greeted with envy.

The Earl had predicted that his move would be followed, and it was. Three new residential squares appeared on the southside, Merrion Square (facing his residence's garden front), St Stephen's Green and the smallest and last of Dublin's five Georgian squares to be built, Fitzwilliam Square. Aristocrats, bishops and the wealthy sold their northside townhouses and migrated to the new southside developments, even though many of the developments, particularly in Fitzwilliam Square, were smaller and less impressive than the buildings in Henrietta Street. While the wealthier people lived in houses on the squares, those with lesser means and lesser titles lived in smaller, less grand but still impressive developments off the main squares, such as Upper and Lower Mount Street and Leeson Street.

Despite the rebuilding of Dublin during this time, sanitation continued to be an issue for the city. With the lack of sewers, the city continued to rely on cesspits. The period was also marked by overcrowding in cemeteries.[3] In 1809, the Paving Board was established to erect lamps, clean and pave the streets, and install sewers.[4]

The Act of Union and Georgian Dublin

[edit]

Although the Irish Parliament was composed exclusively of representatives of the Anglo-Irish Ascendency, the established ruling minority Protestant community in Ireland, it did show significant sparks of independence, most notably the achievement of full legislative independence in 1782, where all the restrictions previously surrounding the powers of the new parliament in College Green, notably Poynings' Law were repealed. This period of legislative freedom however was short-lived.

In 1800, under pressure from the British Government of Mr. Pitt, in the wake of the rebellion of the last years of the century, which was aided and abetted by the French invasion in support of the rebels Dublin Castle administration of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland both the House of Commons and the House of Lords passed the Irish Act of Union, uniting both the Kingdom of Ireland and its parliament with the Kingdom of Great Britain and its parliament in London. As a result, from 1 January 1801 Dublin found itself without a parliament with which to draw hundreds of peers and bishops, along with their thousands of servants. While many did come to Dublin still for the Social Season, where the Lord Lieutenant hosted debutantes balls, state balls and drawing rooms in a period from January until St. Patrick's Day (17 March) every year, many found them less appealing than in the days when they could sit in parliament for a session in College Green. Many of the leading peers, including the Duke of Leinster and Viscount Powerscourt, almost immediately sold their palatial Dublin townhouses, Powerscourt House and Leinster House. Though many still flocked to Dublin every social season, many did not or went to London. The loss of their revenue and that of their extensive staff hurt the Dublin economy severely. While the 'new' Georgian centres southside continued to flourish, the northside Georgian squares soon fell into squalor, as new owners of the buildings crammed in massive numbers of poor into the former residences of earls and bishops, in some cases cramming an entire family into one old drawing room. Mountjoy Square in particular became run-down, until such was its state and degree of dereliction in the 1980s that it was used as a film set for stories set in post-blitz London and post-war Berlin. The empty shells of the graceful houses, reduced to unsanitary tenements before being demolished in the 1980s, were used as a backdrop for a U2 rock video.

Georgian Dublin today

[edit]

In the years after independence in 1922, independent Ireland had little sympathy for Georgian Dublin, viewing it as a symbol of British rule and of the unionist identity that was alien to Irish identity. By this time, many of the gentry who had lived in them had moved elsewhere; some to the wealthy Victorian suburbs of Rathmines and Rathgar, Killiney and Ballsbridge, where Victorian residences were built on larger plots of land, allowing for gardens, rather than the lack of space of the Georgian eras. Those that had not moved in many cases had by the early twentieth century sold their mansions in Dublin. The abolition of the Dublin Castle administration and the Lord Lieutenant in 1922 saw an end to Dublin's traditional "Social Season" of masked balls, drawing rooms and court functions in the Castle. Many of the aristocratic families lost their heirs in the First World War, their homes in the country to IRA burnings (during the Irish War of Independence) and their townhouses to the Stock Market Crash of 1929. Daisy, the Countess of Fingall, in her regularly republished memoirs Seventy Years Young, wrote in the 1920s of the disappearance of that world and of her change from a big townhouse in Dublin, full of servants to a small flat with one maid. By the 1920s and certainly by the 1930s, many of the previous homes in Merrion Square had become business addresses of companies, with only Fitzwilliam Square of all the five squares having any residents. (Curiously, in the 1990s, new wealthy businessmen such as Sir Tony O'Reilly and Dermot Desmond began returning to live in former offices they had bought and converted back into homes.) By the 1930s, plans were discussed in Éamon de Valera's government to demolish all of Merrion Square, perhaps the most intact of the five squares, on the basis that the houses were "old fashioned" and "un-national". These plans were put on hold in 1939 due to the outbreak of World War II and a lack of capital and investment and had been essentially forgotten about by 1945.

Many of the houses had been subdivided into tenement flats, and were often poorly maintained by the owners. In June 1963, two tenement houses collapsed within 10 days. The first happened in early on 2 June, when a house collapsed on Bolton Street, killing two elderly occupants. Then, on 12 June two young girls were killed when two 4-storey tenement houses on Fenian Street collapsed on to the street, crushing them. This led to local residents to call on the authorities to "clear the slums" and crack down on negligent landlords, but also is viewed as clearing the way for developers to demolish the older buildings regardless of their condition.[5] The tenements came to symbolise Dublin's urban poverty, with the focus being on clearing the inner-city slums and demolishing these Georgian structures under the building code as dangerous.[6]

Further destruction of Georgian buildings did occur despite these circumstances. Mountjoy Square, was under threat when a large amount of property on the south side was demolished by property speculators during the 1960s and 70s; even so, buildings with facsimile facades were subsequently built in place, re-completing the square's uniform external appearance. The world's longest row of Georgian houses, running from the corner of Merrion Square down to Leeson Street Bridge, was divided in the early 1960s to demolish part of the row and replace them with a modern styled office block.

By the 1990s, attitudes had changed dramatically. Stricter new planning guidelines sought to protect the remaining Georgian buildings. During this period, a number of old houses in poor repair, which had been refused planning permission, caught fire and burnt to the ground, paved the way for redevelopment.[citation needed] However, in contrast with the lax development controls applied in Ireland for many decades, by the 1990s a changed mindset among politicians, planners and the leaders of Dublin City Council (formerly Dublin Corporation) desired to preserve as much as possible of the remaining Georgian buildings.

Perhaps the biggest irony for some is that residence that marked the move of the aristocrats from the northside to the southside (where the wealthier Dubliners have remained to this day), and that in some ways embodied Georgian Dublin, Leinster House, home of the Duke of Leinster, ended up as the parliament of independent republican Ireland; but his family also produced the republican leader Lord Edward Fitzgerald. The decision in the late 1950s to demolish a row of Georgian houses in Kildare Place and replace them with a brick wall was greeted with jubilation by a republican minister at the time, Kevin Boland, who said they stood for everything he opposed. He described members of the fledgling Irish Georgian Society, newly formed to seek to protect Georgian buildings, of being "belted earls".[7]

Gallery

[edit]-

Townhouses on Mount Street Crescent

-

Townhouses on Baggot Street

-

The Molesworth Gallery, Molesworth Street

-

Highly ornate Georgian doors.

See also

[edit]- Newtown Pery, Georgian Limerick

- Georgian mile, Dublin

References

[edit]Citations

- ^ Bush 1769, p. 9-10.

- ^ "Home". The Honorable Society of King's Inns. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- ^ Maxwell 1997, p. 142.

- ^ Maxwell 1997, p. 153.

- ^ McDonald 1985, p. 23.

- ^ McDonald 1989, p. 19.

- ^ McDonald 1985, p. 12.

Sources

- Bush, John (1769). Hibernia Curiosa: A Letter from a Gentleman in Dublin to his Friend at Dover in Kent, Giving a general View of the Manners, Customs, Dispositions, &c. of the Inhabitants of Ireland. With occasional Observations on the State of Trade and Agriculture in that Kingdom. And including an Account of some of its most remark-able Natural Curiosities, such as Salmon-Leaps, Water-Falls, Cascades, Glynns, Lakes, &c With a more particular Description of the Giant's Cause-way in the North; and of the celebrated Lake of Killarney in the South of Ireland; taken from an attentive Survey and Examination of the Originals. Collected in a Tour Through the Kingdom in the Year 1764 And ornamented with Plans of the principal Originals, engraved from Drawings taken on the Spot. London: London (Printed for W. Flexney, opposite Gray's-Inn-Gate, Holbourn); Dublin (J. Potts and J. Williams).

- McDonald, Frank (1985). The Destruction of Dublin. Gill and MacMillan. ISBN 0-7171-1386-8.

- McDonald, Frank (1989). Saving the City: How to halt the destruction of Dublin. Tomar Publishing. ISBN 1-871793-03-3.

- Saving the City. Tomar Publishing Limited. 1989. ISBN 1-871793-03-3.

- Maxwell, Constantia (1997). Dublin Under the Georges. Lambay Books. ISBN 0-7089-4497-3.

- Ó Gráda, Diarmuid, Georgian Dublin; The Forces That Shaped The City Archived 5 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine (Cork University Press, 2015, ISBN 9781782051473)

Further reading

[edit]- Treacy, Noel. Address on the occasion of the Celebration of the Award to the Hon. Desmond Guinness of the European Union Prize/Europa Nostra Award for Dedicated Service to Heritage Conservation (Speech). Department of the Taoiseach. Archived from the original on 17 June 2008.

External links

[edit]- Civic and Ecclesiastical Architecture of Georgian Dublin Collection. A UCD Digital Library Collection. A selection of 35 mm slides from the collection of the UCD School of Art History and Cultural Policy, focusing on the civic and ecclesiastical architecture of eighteenth-century Dublin.

- Domestic Architecture of Georgian Dublin Collection. A UCD Digital Library Collection. A selection of 35 mm slides from the collection of the UCD School of Art History and Cultural Policy, focusing on the domestic architecture of eighteenth-century Dublin.