Zanni

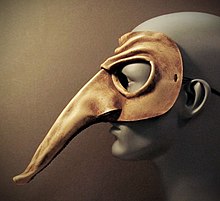

Zanni (Italian: [ˈdzanni]), Zani or Zane is a character type of commedia dell'arte best known as an astute servant and a trickster. The Zanni comes from the countryside and is known to be a "dispossessed immigrant worker".[1][Note 1] Through time, the Zanni grew to be a popular figure who was first seen in commedia as early as the 14th century.[2] The English word zany derives from this character. The longer the nose on the characters mask, the more foolish the character.

Origin of the name

[edit]The name "Zanni" (as well as "Zuan") is a variant of the name Gianni and was common in the Lombard-Venetian countryside which provided most of the servants to the wealthy nobles and merchants of Venice. In Italian it is specifically a name of someone whose identity is not of any importance.[3] It is one of the oldest characters in commedia dell'arte, but over the course of time became subdivided into a number of similar characters with more specific traits. These included Harlequin (Arlecchino), Pulcinella, Mezzettino and Truffaldino, as well as Beltrame and Brighella. Harlequin, for example, was more representative of a jester than an ordinary servant and was frequently depicted as very acrobatic.[4] Zanni was shortened to Zan when used to provide further identification of an individual. For example, Zan Ganassa was the stage name of Alberto Naseli, who was one of the first actors specializing in Zanni roles to perform outside of Italy.[5]

Overall, the Zanni in early commedia dell'arte is the name for the 'carter', which is the servant. The name Zanni became a "technical term to define all of the servants".[6]

Variations

[edit]Some characters in commedia that are derived from Zanni are Harlequin, Brighella, Scapino, Mescolino and Mezzettino, Scaramuccia (aka Scaramouche), Pulcinella, Pedrolino, Giangurgolo, Tartaglia, Trappolino, and Burratino.[7]

Characteristics

[edit]The earliest literary evidence portrays Zanni as a servant of Pantalone. Of all of the commedia archetypes, Zanni's survival instinct is the strongest. Zanni is also always hungry, which leads to a vision of Utopia where "everything is comestible, reminiscent of the followers of gluttony in carnival processions".[Note 2] A Zanni also has an animistic view of the world in that he senses a spirit in everything, so it could be eaten. Zanni is ignorant, loutish, and has no self-awareness. The simple act of thinking does not seem to be natural to Zanni. He is a very faithful individual who prefers to live in the present day. Zanni never looks for a place to sleep; it just seems to happen to him often in situations where it shouldn't, like a drunkard. Lastly, all of his reactions are completely emotional.[8]

Zanni is born into an immigrant background and is known for performing both "duty and necessity" and also plays an active role in the "game" of breaking up and unifying relationships. Zanni is also known for his ability to scheme and manipulate. The role of Zanni is known as being a "stupid genius"; this contradiction prevents Zanni from approaching daily life in a rational manner. Zanni's stupidity prevents him from performing simple tasks, while his genius gives him the ability to make the impossible possible.[6]

Two types of Zanni

[edit]The evolution of the character Zanni was of two distinct types, one of the silly servant and the other of the cunning servant. These two components developed over the course of the history of the commedia dell'arte, and players began to specialize in the two types who were called "first Zanni" and "second Zanni". Mezzetino and Brighella are examples of the first Zanni; Harlequin and Pulcinella are examples of the second.[9] A scenario must always have at least two Zanni.[10]

The first Zanni is known to be clever and witty, and is known as il furbo (lit. 'the clever'). The first Zanni can trick and cheat anyone whom they come across.[10] It is a must that they are cynically sharp. The first Zanni is also known to be the go-between. The job of the first Zanni is to advance the action and give it some movement, with a slightly cynical twist.[10] In some traditions, first Zanni are said to be from Val Brembana, in the province of Bergamo; in others they are attributed to the upper city of Bergamo.[10]

The second Zanni is known as lo stupido. The second Zanni must be foolish, clumsy, and dull. The second Zanni is also unable to tell his right hand from his left. He is a dull-witted peasant who can be simple and also ridiculous.[11] Second Zanni, in particular with Harlequin, does not so much advance plot as maintain a steady stream of comic relief throughout the scenario.[12] Second Zanni are assumed to be from the lower city of Bergamo.[12] Between the two of them they make up one person of "less than average intelligence".[8] Before developing this dualistic person of the two types of clever and silly servant, Zanni was a character in its own right.[citation needed]

Actors

[edit]The performance of a commedia actor relies on the acting itself. A scenario should be playable in different ways and seem different each time the audience sees it. The actors who play Zanni must be clever and equally talented, because an actor's success relies primarily on their dialogue partner. If the partner does not reply to them at the right moment or interrupts them in the wrong place, the actor's "discourse falters and the liveliness of their wit is extinguished".[13] He must be acrobatic, able to walk on his hands and on stilts, dance, skip and somersault. In this respect, the Zanni is one of the most physically demanding of all the Masks.[14]

Costume and mask

[edit]

The Zanni's costume usually consists of white baggy clothing. This clothing was traditionally made out of flour sacks.[15] This was similar to the dress of peasants and farmworkers of the time. A specific type of Zanni, Brighella, wore accents of green to indicate his tricky and devious nature.[16] Harlequin, however, was known for his irregular colored patches that eventually became the essence of the entire outfit.[17] The Zanni are also known to sport a peaked hat and a wooden sword.[18] The Zanni at first wore a full faced carnival mask, but because of the need for dialogue between Pantalone and the Zanni, the bottom of the mask was hinged and eventually cut away altogether. The longer the nose of the Zanni, the stupider he is said to be.[15]

Stance

[edit]The stance of Zanni has a "lowered centre of gravity" either from the earth or from carrying heavy bags and chairs.[19] Zanni's back is arched when he stands up and his knees are bent and apart with splayed feet. The support knee is bent and the other leg is extended with his toe pointed. He switches his feet a lot while speaking or listening within the same position, and without his head moving up and down. Zanni's elbows are usually bent and arms half lifted. Zanni also has a variety of poses. These include crouching with the elbows on the knees and the chin in the hands, or sitting with the feet splayed bending at the hips with the elbows slightly elevated.[15]

Six types of walks

[edit]In commedia, Zanni has a variety of at least six different types of walks. These walks include The Little Zanni, The Big Zanni, Zanni Running, Zanni Jubilant, Vain Zanni, and Soldier Zanni.

The Little Zanni walk is a development of a basic stance. The Zanni's feet are constantly changing but on each shift, The Zanni takes a tiny step forward. The feet are to be pointed, shoulders down, and elbows forward. The Zanni's knees come high off of the ground and to the side. The Zanni's head is to peck like a chicken, but the Zanni have to be sure not to bob their head up and down. A two-time rhythm is used with even beats.[20]

The Big Zanni walk includes sticking the chest forward and the backside up. The feet need to be in fourth extended with the knees bent. The Zanni has to lower his center of gravity. This walk can be used by a Zanni when he pretends to cross the stage without being seen or when he wants to get himself out of a difficult situation.[21]

Zanni Running includes swift movements with legs kicking out in front of him with his toes pointed. His arms move opposite to his legs.[21]

Zanni Jubilant involves skipping on his toes with his center of gravity moving from side to side. This type of walk also involves the hands being placed on the belt.[21]

Vain Zanni's steps are a smaller version of the Big Zanni walk with the hands placed on the belt as seen in the Zanni Jubilant. When the Zanni's leg lifts, his chest is forward and his arms are in the position of a chicken. This type of walk is used when the Zanni has a "...new button or a feather on his cap".[21]

Soldier Zanni holds a stick in one hand and inclines it over his shoulder like he is holding a rifle. The Zanni marches with his shoulders moving up and down in a two-time rhythm but in three beats: "tramper-tramp, tramper-tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp....".[21]

Speech

[edit]The Zanni is loud and his voice is coarse due to making a living outdoors trying to be heard in a market or busy street.[21] Zanni is also known to be vocal with sounds including farting, burping, and snoring.[22]

The following sample dialogue shows how the Zanni uses his speech in commedia:

- Pantalone: Zanni, I want you to earn yourself a sovereign.

- Zanni: A gold coin?

- Pantalone: A gold castle.

- Zanni: Ah, right (He lies down and falls asleep).

- Pantalone: Zanni, wake up you animal and come here.

- Zanni (rising): At your service, boss, as always.

- Pantalone: Dear Zanni, take the sonnet.

- Zanni: Give me the sovereign first.

- Pantalone: I will give it to you.

- Zanni: Where is it, then?

- Pantalone: It's there.

- Zanni: Show it to me.

- Pantalone: There it is.

- (Zanni tries to snatch the coin but Pantalone grabs it back at the last moment)

- Zanni: Darn!

- Pantalone: It's yours.

- Zanni: How can it be mine since you’ve got it?

- Pantalone: Trust me, my dear Zanni; take the sonnet and I will give it to you.

Lazzi

[edit]A lazzo is a joke or gag in mime or in words.[24]

The following lazzi examples are short comic routines by the character type Zanni.

In "Lazzi of the Cat" the Zanni mimics the actions of a cat, demonstrating how the cat hunts for wild birds or how the cat cleans himself by scratching his ears with his feet and cleaning his body with his mouth.[25]

Sexual / Scatological Lazzi: in "Lazzi of Burying the Urine", the Zanni is told that burying his urine and the urine produced by his wife will give him a son. Zanni gets a urinal that produces both and before he spills it into the soil, he treats it as a special fluid.[26]

Stupidity/ Inappropriate Behavior: in "Lazzi of Counting Money", the Zanni divides Pantalone's money between Pantalone and himself in the following way: "One for Pantalone, two for me (gives one coin to Pantalone and two to himself); two for Pantalone, three for me (gives one coin to Pantalone and three to himself), etc."[27][Note 3]

Another popular lazzi was Zanni walking behind his master mounted on a mule and goading it to go faster by blowing air from a pair of bellows onto the animal's anus.[citation needed]

Props

[edit]A Zanni is known to take and briefly keep items that belong to someone else. Some items that the Zanni would keep would be bags, letters, valuables, or food.[15]

Relationship with the audience

[edit]Zanni's relationship to the audience is that he is the most sympathetic character and treats the audience collectively so he is able to address the audience directly. Zanni contributes to the plot by being the "principal contributor to any confusion".[8]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Immigrant" in Italy at the time of the city-states did not mean someone from outside of Italy but rather someone from outside the city, an itinerant worker.

- ^ A famous example is the Truffaldino in A Servant of Two Masters by Goldoni.

- ^ In the 1958 film, tom thumb, two characters played by Terry-Thomas and Peter Sellers perform this lazzo.

References

[edit]- ^ Rudlin, John. Commedia dell'arte: An Actors Handbook. London: Routledge, 1994. 67. Print.

- ^ Nicoll M.A., Allardyce. Masks Mimes and Miracles: Studies in the Popular Theatre. New York: Cooper Square Publishers, INC., 1963. 263. Print.

- ^ John., Rudlin (1 January 1994). Commedia dell'arte : an actor's handbook. Routledge. p. 67. OCLC 27976194.

- ^ Duchartre, Pierre Louis. The Italian Comedy: The Improvisation Scenarios Lives Attributes Portraits and Masks of the Illustrious Characters of the Commedia dell' Arte. Canada: Dover Publications, 1966.

- ^ Hartnoll 1983, p. 313.

- ^ a b Fava, Antonio (2006). "Commedia by Fava: The Commedia Dell' Arte, Step by Step - Part 1". Alexander Street.

- ^ Nicoll M.A., Allardyce. Masks Mimes and Miracles: Studies In The Popular Theatre. New York: Cooper Square Publishers, INC., 1963. 266. Print.

- ^ a b c Rudlin, John. Commedia dell'arte: An Actors Handbook. London: Routledge, 1994. 71. Print.

- ^ "Sipario". Sipario.it. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

- ^ a b c d Oreglia, Giacomo (1 January 1968). The Commedia dell'Arte. Hill & Wang. p. 71. OCLC 939808594.

- ^ Nicoll M.A., Allardyce. Masks Mimes and Miracles: Studies In The Popular Theatre. New York: Cooper Square Publishers, INC., 1963. 265-266. Print.

- ^ a b Oreglia, Giacomo (1 January 1968). The Commedia dell'Arte. Hill & Wang. p. 56. OCLC 939808594.

- ^ Duchartre, Pierre Louis. The Italian Comedy: The Improvisation Scenarios Lives Attributes Portraits and Masks of the Illustrious Characters of the Commedia dell' Arte. Canada: Dover Publications, Inc, 1966. 32. Print.

- ^ Oreglia, Giacomo (1 January 1968). The Commedia dell'Arte. Hill & Wang. p. 58. OCLC 939808594.

- ^ a b c d Rudlin, John. Commedia dell'arte: An Actors Handbook. London: Routledge, 1994. 68. Print.

- ^ Oreglia, Giacomo (1 January 1968). The Commedia dell'Arte. Hill & Wang. p. 72. OCLC 939808594.

- ^ Oreglia, Giacomo (1 January 1968). The Commedia dell'Arte. Hill & Wang. p. 57. OCLC 939808594.

- ^ Nicoll M.A., Allardyce. Masks Mimes and Miracles: Studies In The Popular Theater. New York: Cooper Square Publishers, INC., 1963. 265. Print.

- ^ John., Rudlin (1 January 1994). Commedia dell'arte : an actor's handbook. Routledge. p. 69. OCLC 27976194.

- ^ Rudlin, John. Commedia dell'arte: An Actors Handbook. London: Routledge, 1994. 69-70. Print.

- ^ a b c d e f Rudlin, John. Commedia dell'arte An Actors Handbook. London: Routledge, 1994. 70. Print.

- ^ "Description of Commedia dell'Arte characters". www.italymask.co.nz. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ Rudlin, John. Commedia dell'arte: An Actors Handbook. London: Routledge, 1994. 73-74. Print.

- ^ Oreglia, Giacomo (1 January 1968). The Commedia dell'Arte. Hill & Wang. p. 11. OCLC 939808594.

- ^ Gordon, Mel. Lazzi: The Comic Routines of the Commedia dell'arte. First. New York: Performing Arts Journal Publication, 1983.11. Print.

- ^ Gordon, Mel. Lazzi: The Comic Routines of the Commedia dell'arte. First. New York: Performing Arts Journal Publication, 1983.32. Print.

- ^ Gordon, Mel. Lazzi: The Comic Routines of the Commedia dell'arte. First. New York: Performing Arts Journal Publication, 1983.43. Print.

Further reading

[edit]- Hartnoll, Phyllis (1983). The Oxford Companion to the Theatre (fourth edition). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-211546-1.