Sobekneferu

| Sobekneferu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neferusobek Scemiophris from Greek: Σκεμίοφρις | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

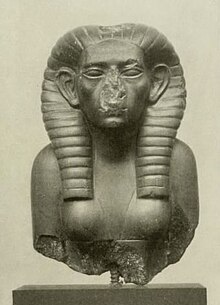

Statue of Sobekneferu which was lost during World War II | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 3 years, 10 months, and 24 days according to the Turin Canon in the mid-18th century BC[1][2][a] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Amenemhat IV | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Sobekhotep I or Wegaf | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Amenemhat IV? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Amenemhat III | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Northern Mazghuna pyramid? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Twelfth Dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sobekneferu or Neferusobek (Ancient Egyptian: Sbk-nfrw meaning 'Beauty of Sobek') was a pharaoh of ancient Egypt and the last ruler of the Twelfth Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom. She ascended to the throne following the death of Amenemhat IV, possibly her brother or husband, though their relationship is unproven. Instead, she asserted legitimacy through her father Amenemhat III. Her reign lasted 3 years, 10 months, and 24 days, according to the Turin King List.

Distinguishing herself from prior female rulers, Sobekneferu adopted the full royal titulary. She was also the first ruler to associate herself with the crocodile god Sobek through her name. Contemporary evidence for her reign is scant. There are a few partial statues – one with her face – and inscriptions that have been uncovered. It is assumed that the Northern Mazghuna pyramid was intended for her, though this assignment is speculative with no firm evidence to confirm it. The monument was abandoned immediately after its substructure was completed. A papyrus discovered in Harageh mentions a place called Sekhem Sobekneferu that may refer to the pyramid. Her rule is attested on several king lists.

Family

[edit]

Sobekneferu is thought to be the daughter of Pharaoh Amenemhat III,[5][18] but her mother's identity is unknown.[19] Amenemhat III had two known wives, Aat and an unnamed queen, both buried in his pyramid at Dahshur. He had at least one other daughter, Neferuptah, who had a burial at his second pyramid at Hawara that was eventually moved to her own pyramid.[20] Neferuptah appears to have been groomed as Amenemhat III's heir as she had her name enclosed in a cartouche.[21] Evidence of burials of three other princesses – Hathorhotep, Nubhotepet, and Sithathor – were found at the Dahshur complex, but it is not clear whether these princesses were his daughters as the complex was used for royal burials throughout the Thirteenth Dynasty.[22]

Amenemhat III's eventual heir, Amenemhat IV, is attested to be the son of Hetepti, though her titulary lacks reference to her being a 'King's Wife'.[23] The relationship between Amenemhat IV and Sobekneferu remains unclear. According to the ancient historian Manetho in Aegyptiaca they were brother and sister.[5] According to Gae Callender they were also probably married.[24] Although, neither the title of 'King's Wife' nor 'King's Sister' are attested for Sobekneferu.[19] Sobekneferu's accession may have been motivated by the lack of a male heir for Amenemhat IV.[5] However, two kings of the Thirteenth Dynasty, Sobekhotep I and Sonbef, have been identified as possible sons of his based on their shared nomen 'Amenemhat'.[25] As such, Sobekneferu may have usurped the throne after Amenemhat IV's death, viewing his heirs as illegitimate.[26]

Female kingship

[edit]Sobekneferu was one of the few women that ruled in Egypt,[27][28] and the first to adopt the full royal titulary, distinguishing herself from any prior female rulers.[5][29] She was also the first ruler associated with the crocodile god Sobek by name, whose identity appears in both her birth and throne names.[30] Kara Cooney views ancient Egypt as unique in allowing women to acquire formal – and absolute – power. She posits that women were elevated to the throne during crises to guide the civilization and maintain social order. Though, she also notes that, this elevation to power was illusory. Women acquired the throne as temporary replacements for a male leader; their reigns were regularly targeted for erasure by their successors; and overall, Egyptian society was oppressive to women.[31]

In ancient Egyptian historiography, there is some evidence for other female rulers. As early as the First Dynasty, Merneith is proposed to have ruled as regent for her son.[32] In the Fifth Dynasty, Setibhor may have been a female king regnant based on the manner her monuments were targets for destruction.[33] Another candidate, Nitocris, is generally considered to have ruled in the Sixth Dynasty,[34] though there is little proof of her historicity[33][35] and she is not mentioned before the Eighteenth Dynasty.[34] The kingship of Nitocris may instead be a Greek legend[35] and that the name originated with an incorrect translation of the name of the male pharaoh Neitiqerty Siptah.[36]

Reign

[edit]The Middle Kingdom was in decline by the time of Sobekneferu's accession.[37] The peak of the Middle Kingdom is attributed to Senusret III and Amenemhat III.[38][39] Senusret III formed the basis for the legendary character Sesostris described by Manetho and Herodotus.[40][41] He led military expeditions into Nubia and into Syria-Palestine[42][43] and built a 60-metre-tall (200 ft) mudbrick pyramid as his monument.[44] He reigned for 39 years, as evidenced by an inscription in Abydos, where he was buried.[45] Amenemhat III, in contrast, presided over a peaceful Egypt that consisted of monumental constructions, the development of Faiyum, numerous mining expeditions, and the building of two pyramids at Dahshur and at Hawara.[46][47] His reign lasted at least 45 years, probably longer.[24] Nicolas Grimal notes that such long reigns contributed to the end of the Twelfth Dynasty, but without the collapse that ended the Old Kingdom.[37] Amenemhat IV ruled for nine or ten years.[48] There is little information regarding his reign.[24]

It is to this backdrop that Sobekneferu acquired the throne.[37] She reigned for around four years, but as with her predecessor, there are few surviving records.[49] Her death brought a close to the Twelfth Dynasty[50][51] and began the Second Intermediate Period spanning the following two centuries.[52]

This period is poorly understood owing to the paucity of references to the rulers of the time.[53] She was succeeded by either Sobekhotep I[54] or Wegaf,[55] who inaugurated the Thirteenth Dynasty.[37] Stephen Quirke proposed, based on the numerosity of kingships and brevity of their rule, that a rotating succession of kings from Egypt's most powerful families took the throne.[49][56] They retained Itj-tawy as their capital through the Thirteenth Dynasty.[57][58] Their role, however, was relegated to a much lesser status than earlier and power rested within the administration.[56][58] It is generally accepted that Egypt remained unified until late into the dynasty.[57] Kim Ryholt contends that the Fourteenth Dynasty instead arose in the Nile Delta at the end of Sobekneferu's reign as a rival to the Thirteenth.[59] Thomas Schneider argues that the evidence for this hypothesis is weak.[60]

Attestations

[edit]Only a small collection of sources attest to Sobekneferu's rule as pharaoh of Egypt.[49]

Contemporary evidence

[edit]Graffiti

[edit]In Nubia, a graffito in the fortress of Kumma records the height of the Nile inundation at 1.83 m (6 ft) during her third regnal year.[48][49] Another inscription discovered in the Eastern Desert records "year 4, second month of the Season of the Emergence".[61]

Cylinder and scarab seals

[edit]The British Museum has a fine cylinder seal (EA16581) bearing her name and royal titulary in its collection.[49][62] The seal is made of glazed steatite and is 4.42 cm (1.74 in) long with a diameter of 1.55 cm (0.61 in).[63] The British Museum also possesses an inscribed scarab (EA66159), measuring 2.03 cm (0.80 in) by 1.32 cm (0.52 in) and 0.86 cm (0.34 in) in height, made of glazed steatite bearing the name of Sobekneferu.[64]

Statuary

[edit]

A handful of headless statues of Sobekneferu have been identified.[5][49][66] In one quartzite image, she blends feminine and masculine dress with an inscription reading 'daughter of Re(?), of his body, Sobekneferu, may she live like Re forever'.[49][66] On her torso rests a pendant modelled on that worn by Senusret III.[66] Three basalt statues of the female king were found in Tell ed-Dab'a;[67] two depict her in a seated posture, another shows her kneeling.[68][69] In one, she is depicted trampling the Nine Bows, representing the subjugation of Egypt's enemies.[5] The three statues appear to be life-sized.[69] One statue with her head is known. The bust was held in the Egyptian Museum of Berlin but was lost during World War II. Its existence is confirmed by photographic images and plaster casts. It fits on top of the lower part of a seated statuette discovered at Semna which bears the royal symbol smꜣ tꜣwy on the side of the throne.[70] The lower half is held at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.[71][72]

Buildings

[edit]There is evidence that she had structures built in Heracleopolis Magna and added to the Pyramid of Amenemhat III in Hawara.[49] She left inscriptions on four granite papyriform columns found at a temple in Kom el-Akârib, while a further ten granite beams there may date to the same period.[73] Her monumental works consistently associate her with Amenemhat III rather than Amenemhat IV, supporting the theory that she was the royal daughter of Amenemhat III and perhaps only a stepsister to Amenemhat IV, whose mother was not royal. Contemporary sources from her reign show that Sobekneferu adopted only the 'King's Daughter' title, which further supports this hypothesis.[74] An example of such an inscription comes from a limestone block of 'the Labyrinth' of the Pyramid at Hawara. It reads 'Beloved of Dḥdḥt the good god Nỉ-mꜣꜥt-rꜥ [Amenemhat III] given [...] * Daughter of Re, Sobekneferu lord of Shedet, given all life'. The inscription is also the only known reference to a goddess Dḥdḥt.[75][76] By contrast, Amenemhat IV's name does not appear at Hawara.[77]

-

Columns inscribed with the names of Amenemhat III and Sobekneferu, from the Egyptian Museum, Cairo

Uncertain attestations

[edit]In Israel, a possible reference to Sobekneferu before she became a ruler is found on the base of a statue discovered in Gezer. This statue bears her name and is identified as a representation of a "king's daughter". However, it may also refer to a daughter of Senusret I or another unknown Sobekneferu.[74][78] A damaged statuette (MET 65.59.1) in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has been suggested to represent Sobekneferu, though this assignment is unverified.[71] The schist bust depicts a woman in a wig, wearing a crown composed of a uraeus cobra and two vultures with outstretched wings which is of unknown iconography, and the ḥb-sd cloak.[49][79] A headless black basalt or granite sphinx discovered by Édouard Naville in Qantir bearing a damaged inscription is also assigned to Sobekneferu.[80][81]

-

Damaged statuette of a Late Middle Kingdom Queen in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, possibly depicting Sobekneferu

-

The unique twin vultures with wings outstretched either side of a uraeus cobra which winds through the centre of the subject's head

Non-contemporary sources

[edit]In the Thutmosid period, she is mentioned on the Karnak list of early Egyptian kings.[82] In the Ramesside period, she is mentioned in the Saqqara Tablet,[83] and Turin King List,[49] but is conspicuously excluded from the Abydos King List.[84] Her exclusion, along with all other female kings, pharaohs of the First and Second Intermediate Periods, and of the Amarna Period, is an indicator of whom Ramesses II and Seti I viewed as the legitimate rulers of Egypt.[84] She is credited in the Turin Canon with a reign of 3 years, 10 months, and 24 days.[48][85][86] In the Hellenistic period, she is mentioned by Manetho as 'Scemiophris' (Σκεμιoφρις), where she is credited with a reign of four years.[87]

Burial

[edit]Sobekneferu's tomb has not yet been positively identified. A place called Sekhem Sobekneferu is mentioned on a papyrus found at Harageh which may be the name of her pyramid.[88][89] On a funerary stela from Abydos, now in Marseille, there is mention of a storeroom administrator of Sobekneferu named Heby. The stela dates to the 13th Dynasty and attests to an ongoing funerary cult.[90][91]

The Northern Mazghuna pyramid is assumed to be her monument. There is, however, no clear evidence to confirm this assignment[92][93] and the pyramid may date to a period well after the end of the Twelfth Dynasty.[94] Only its substructure was completed; construction of the superstructure and wider temple complex was never begun. The passages of the substructure had a complex plan. A stairway descended south from the east side of the pyramid leading to a square chamber which connected to the next sloping passage leading west to a portcullis. The portcullis consisted of a 42,000-kilogram (93,000 lb) quartzite block intended to slide into and block the passage. Beyond the passage wound through several more turns and a second smaller portcullis before terminating at the antechamber. South of this lay the burial chamber which was almost entirely occupied by a quartzite monolith which acted as the vessel for a sarcophagus. In a deep recess lay a quartzite lid which was to be slid into place over the coffin and then locked into place by a stone slab blocking it. The builders had all exposed surfaces painted red and added lines of black paint. A causeway leading to the pyramid was built of mudbrick, which must have been used by the workers. Though the burial place had been constructed, no burial was interred at the site.[93][94]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Schneider 2006, p. 174.

- ^ a b Krauss & Warburton 2006, pp. 480 & 492.

- ^ Keller 2005, p. 294.

- ^ Oppenheim et al. 2015, p. xix.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gillam 2001, p. 301.

- ^ Redford 2001, Egyptian King List.

- ^ Grimal 1992, p. 391.

- ^ Lehner 2008, p. 8.

- ^ Clayton 1994, p. 84.

- ^ Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 289.

- ^ Shaw 2003, p. 483.

- ^ Cooney 2018, p. 6.

- ^ Wilkinson 2010, p. xv.

- ^ a b c d e Leprohon 2013, p. 60.

- ^ Cooney 2018, p. 87.

- ^ Cooney 2018, p. 88.

- ^ The British Museum n.d., Description.

- ^ Dodson & Hilton 2004, pp. 92 & 95.

- ^ a b Zecchi 2010, p. 84.

- ^ Dodson & Hilton 2004, pp. 93, 95–96 & 99.

- ^ Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 98.

- ^ Dodson & Hilton 2004, pp. 92, 95–98.

- ^ Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 95.

- ^ a b c Callender 2003, p. 158.

- ^ Dodson & Hilton 2004, pp. 102 & 104.

- ^ Ryholt 1997, p. 294.

- ^ Cooney 2018, pp. 12 & 14.

- ^ Wilkinson 2010, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Robins 2001, p. 108.

- ^ Zecchi 2010, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Cooney 2018, pp. 9–13.

- ^ Cooney 2018, p. 30.

- ^ a b Roth 2005, p. 12.

- ^ a b Ryholt 2000, p. 92.

- ^ a b Cooney 2018, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Ryholt 2000, pp. 92–93.

- ^ a b c d Grimal 1992, p. 171.

- ^ Callender 2003, pp. 154–158.

- ^ Grimal 1992, pp. 166–170.

- ^ Grimal 1992, p. 166.

- ^ Callender 2003, p. 154.

- ^ Callender 2003, pp. 154–155.

- ^ Grimal 1992, p. 168.

- ^ Callender 2003, p. 156.

- ^ Schneider 2006, p. 172.

- ^ Callender 2003, pp. 156–158.

- ^ Grimal 1992, p. 170.

- ^ a b c Schneider 2006, p. 173.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Callender 2003, p. 159.

- ^ Gillam 2001, p. 403.

- ^ Simpson 2001, p. 456.

- ^ Grimal 1992, p. 182.

- ^ Ryholt 1997, p. 2.

- ^ Dodson & Hilton 2004, pp. 100&102.

- ^ Callender 2003, pp. 159–160.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 2010, p. 131.

- ^ a b Quirke 2001, p. 394.

- ^ a b Grimal 1992, p. 183.

- ^ Ryholt 1997, p. 75.

- ^ Schneider 2006, p. 177.

- ^ Almásy & Kiss 2010, pp. 174–175.

- ^ The British Museum n.d.b, description.

- ^ The British Museum n.d.b, materials, technique & dimensions.

- ^ The British Museum n.d.c, description & dimensions.

- ^ Petrie 1917, p. pl. XIV.

- ^ a b c Berman & Letellier 1996, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Bietak 1999, p. 950.

- ^ Cooney 2018, p. 338.

- ^ a b Habachi 1954, pp. 458–460.

- ^ Fay et al. 2015, pp. 89–91.

- ^ a b Cooney 2018, p. 339.

- ^ MFA n.d.

- ^ Arnold 1996, p. 46.

- ^ a b Ryholt 1997, p. 213.

- ^ Uphill 2010, p. 34.

- ^ Petrie 1890, p. Pl. XI.

- ^ Zecchi 2010, p. 85.

- ^ Weinstein 1974, pp. 51–53.

- ^ MMA n.d.

- ^ Habachi 1954, p. 462.

- ^ Louvre n.d., Chambre des Ancêtres.

- ^ Hawass 2010, pp. 154–157.

- ^ a b The British Museum n.d., curator's comments.

- ^ Ryholt 1997, p. 15.

- ^ Malék 1982, p. 97, fig. 2, col. 10, row. 2.

- ^ Waddell, Manetho & Ptolemy 1964, p. 69.

- ^ Cooney 2018, p. 96.

- ^ The Petrie Museum n.d.

- ^ Siesse 2019, p. 130.

- ^ Ilin-Tomich n.d.

- ^ Lehner 2008, p. 184.

- ^ a b Verner 2001, p. 433.

- ^ a b Lehner 2008, p. 185.

Bibliography

[edit]General sources

[edit]- Almásy, Adrienn; Kiss, Enikő (2010). "Catalogue by Adrienn Almásy and Enikő Kiss". In Luft, Ulrich; Adrienn, Almásy (eds.). Bi'r Minayh, Report on the Survey 1998-2004. Studia Aegyptiaca. Budapest: Archaeolingua. pp. 173–193. ISBN 978-9639911116.

- Arnold, Dieter (1996). "Hypostyle Halls of the Old and Middle Kingdoms". In Der Manuelian, Peter (ed.). Studies in Honor of William Kelly Simpson. Vol. 1. Boston, MA: Museum of Fine Arts. pp. 38–54. ISBN 0-87846-390-9.

- Berman, Lawrence; Letellier, Bernadette (1996). Pharaohs : Treasures of Egyptian Art from the Louvre. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-521235-5.

- Bietak, Manfred (1999). "Tell ed-Dab'a, Second Intermediate Period". In Bard, Kathryn (ed.). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London; New York: Routledge. pp. 949–953. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.

- "Chambre des Ancêtres". Louvre. n.d. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- "EA117". The British Museum. n.d. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- "EA16581". The British Museum. n.d. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- "EA66159". TheBritish Museum. n.d. Retrieved 8 August 2024.

- Callender, Gae (2003). "The Middle Kingdom Renaissance (c. 2055–1650 BC)". In Shaw, Ian (ed.). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 137–171. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Clayton, Peter A. (1994). Chronicle of the Pharaohs. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05074-3.

- Cooney, Kara (2018). When Women Ruled the World: Six Queens of Egypt. Washington, DC: National Geographic. ISBN 978-1-4262-1977-1.

- Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05128-3.

- Fay, Biri; Freed, Rita; Schelper, Thomas; Seyfried, Friederike (2015). "Neferusobek Project: Part I". In Miniaci, Gianluci; Grajetzki, Wolfram (eds.). The World of Middle Kingdom Egypt (2000-1550 BC). Vol. I. London: Golden House Publications. pp. 89–91. ISBN 978-1906137434.

- Gillam, Robyn (2001). "Sobekneferu". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt. Translated by Ian Shaw. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-19396-8.

- Habachi, Labib (1954). "Khatâ'na-Qantîr : Importance". Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte. Vol. 52. Le Caire: L'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale. pp. 443–559. OCLC 851266710.

- Hawass, Zahi (2010). Inside the Egyptian Museum with Zahi Hawass. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-416-364-7.

- Ilin Tomich, Alexander (n.d.). "Hbjj on 'Persons and Names of the Middle Kingdom'". Johannes Gutenberg Universität Mainz. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- Keller, Cathleen (2005). "Hatshepsut's Reputation in History". In Roehrig, Catharine (ed.). Hatshepsut From Queen to Pharaoh. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 294–298. ISBN 1-58839-173-6.

- Krauss, Rolf; Warburton, David (2006). "Conclusions and Chronological Tables". In Hornung, Erik; Krauss, Rolf; Warburton, David (eds.). Ancient Egyptian Chronology. Leiden: Brill. pp. 473–498. ISBN 978-90-04-11385-5.

- Lehner, Mark (2008). The Complete Pyramids. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28547-3.

- Leprohon, Ronald J. (2013). The Great Name: Ancient Egyptian Royal Titulary. Writings from the ancient world. Vol. 33. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-736-2.

- "Lower body fragment of a female statue seated on a throne". MFA. Museum of Fine Arts Boston. n.d. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- Malék, Jaromír (1982). "The Original Version of the Royal Canon of Turin". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 68: 93–106. doi:10.2307/3821628. JSTOR 3821628.

- Naville, Édouard (1887). Goshen and The Shrine of Saft El-Henneh (1885). Memoir of the Egypt Exploration Fund. Vol. 5. London: Trübner & Co. OCLC 3737680.

- Quirke, Stephen (2001). "Thirteenth Dynasty". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 394–398. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Redford, Donald B., ed. (2001). "Egyptian King List". The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 621–622. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Robins, Gay (2001). "Queens". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 105–109. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Roth, Ann Macy (2005). "Models of Authority : Hatshepsut's Predecessors in Power". In Roehrig, Catharine (ed.). Hatshepsut From Queen to Pharaoh. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 1-58839-173-6.

- Ryholt, Kim (1997). The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period, c. 1800-1550 B.C. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 87-7289-421-0.

- Ryholt, Kim (2000). "The Late Old Kingdom in the Turin King-list and the Identity of Nitocris". Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde. 127 (1): 87–119. doi:10.1524/zaes.2000.127.1.87. ISSN 0044-216X. S2CID 159962784.

- Schneider, Thomas (2006). "The Relative Chronology of the Middle Kingdom and the Hyksos Period (Dyns. 12-17)". In Hornung, Erik; Krauss, Rolf; Warburton, David (eds.). Ancient Egyptian Chronology. Leiden: Brill. pp. 168–196. ISBN 978-90-04-11385-5.

- Oppenheim, Adela; Arnold, Dorothea; Arnold, Dieter; Yamamoto, Kumiko, eds. (2015). Ancient Egypt Transformed: the Middle Kingdom. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9781588395641.

- Shaw, Ian, ed. (2003). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Siesse, Julie (2019). La XIIIe Dynastie. Paris: Sorbonne Université Presses. ISBN 979-10-231-0567-4.

- Simpson, William Kelly (2001). "Twelfth Dynasty". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 453–457. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- "Statuette of a Late Middle Kingdom Queen". The MET. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. n.d. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- "UC32778". UCL Museums & Collections. The Petrie Museum. n.d. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

- Uphill, Eric (2010). Pharaoh's Gateway to Eternity : The Hawara Labyrinth of Amenemhat III. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7103-0627-2.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001). The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-1703-8.

- Waddell, William Gillan; Manetho; Ptolemy (1964) [1940]. Page, Thomas Ethelbert; Capps, Edward; Rouse, William Henry Denham; Post, Levi Arnold; Warmington, Eric Herbert (eds.). Manetho with an English Translation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. OCLC 610359927.

- Weinstein, James (1974). "A Statuette of the Princess Sobeknefru at Tell Gezer". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 213 (213): 49–57. doi:10.2307/1356083. ISSN 2161-8062. JSTOR 1356083. S2CID 164156906.

- Wilkinson, Toby (2010). The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4088-1002-6.

- Zecchi, Marco (2010). Sobek of Shedet : The Crocodile God in the Fayyum in the Dynastic Period. Studi sull'antico Egitto. Todi: Tau Editrice. ISBN 978-88-6244-115-5.

Royal titulary

[edit]- Burchardt, Max; Pieper, Max (1912). Handbuch der Aegyptischen Königsnamen (in German). Leipzig: J. C. Hindrichs. OCLC 1154955005.

- Gauthier, Henri (1907). Le livre des rois d'Égypte : recueil de titres et protocoles royaux, suivi d'un index alphabétique. Des origines à la fin de la XIIe dynastie (in French). Vol. 17. Cairo: L'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale. OCLC 600626180.

- Newberry, Percy E. (1908). Scarabs : An Introduction to the Study of Egyptian Seals and Signet Rings. London: Archibald Constable and Co. Ltd. OCLC 1015423361.

- Petrie, Flinders (1890). Kahun, Gurob, and Hawara. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, and Co. OCLC 247721143.

- Petrie, Flinders (1917). Scarabs and Cylinders with names : illustrated by the Egyptian collection in University College, London. London: School of Archaeology in Egypt. OCLC 638808928.

- von Beckerath, Jürgen (1984). Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen. München: Deutscher Kunstverlag. ISBN 9783422008328.