William Ralph Inge

William Ralph Inge | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | William Ralph Inge 6 June 1860 |

| Died | 26 February 1954 (aged 93) Wallingford, Oxfordshire, England |

| Alma mater | King's College, Cambridge |

| Spouse |

Mary Catharine Inge

(m. 1905; died 1949) |

| Children | 5 |

| Church | Church of England |

Offices held | Vicar of All Saints, Knightsbridge (1905–1907) Lady Margaret's Professor of Divinity (1907–1911) Dean of St Paul's (1911–1934) |

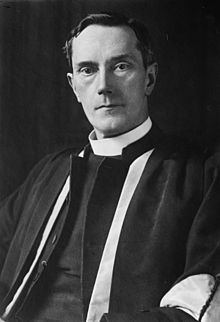

William Ralph Inge KCVO FBA (/ˈɪŋ/;[1] 6 June 1860 – 26 February 1954) was an English author, Anglican priest, professor of divinity at Cambridge, and dean of St Paul's Cathedral. Although as an author he used W. R. Inge, and he was personally known as Ralph,[2] he was widely known by his title as Dean Inge. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature three times.[3]

Early life and education

[edit]

He was born on 6 June 1860 in Crayke, Yorkshire, where his father, Rev. William Inge (later Provost of Worcester College, Oxford), was then curate. His mother was Susanna Churton, daughter of Edward Churton, Archdeacon of Cleveland.

Inge was educated at Eton College, where he was a King's Scholar and won the Newcastle Scholarship in 1879. In 1879, he went on to King's College, Cambridge, where he won a number of prizes including the Chancellor's Medal, as well as taking firsts in both parts of the Classical Tripos.[4]

Career

[edit]Positions held

[edit]Inge was an assistant master at Eton from 1884 to 1888, and a Fellow of King's College from 1886 to 1888.[4]

In the Church of England, he was ordained deacon in 1888, and priest in 1892.[4]

He was a Fellow and Tutor at Hertford College, Oxford from 1889 to 1904.[5]

His only parochial position was as vicar of All Saints, Knightsbridge, London, from 1905 to 1907.[4]

In 1907, he moved to Jesus College, Cambridge, on being appointed Lady Margaret's Professor of Divinity.

In 1911, he became Dean of St Paul's Cathedral in London. He served as president of the Aristotelian Society at Cambridge from 1920 to 1921.

He retired from full-time church ministry in 1934.

Inge was also a trustee of London's National Portrait Gallery from 1921 until 1951.

Writing

[edit]Inge was a prolific author. In addition to scores of articles, lectures and sermons, he also wrote over 35 books.[6] Inge was a columnist for the Evening Standard for many years, finishing in 1946.

He is best known for his works on Plotinus[6] and neoplatonic philosophy, and on Christian mysticism, but also wrote on general topics of life and current politics.

He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature three times.[3]

Views

[edit]Inge was a strong proponent of the spiritual type of religion—"that autonomous faith which rests upon experience and individual inspiration"—as opposed to one of coercive authority. He was therefore outspoken in his criticisms of the Roman Catholic Church. His thought, on the whole, represents a blending of traditional Christian theology with elements of Platonic philosophy. He shares this in common with one of his favourite writers, Benjamin Whichcote, the first of the Cambridge Platonists.

He was nicknamed 'The Gloomy Dean' because of his pessimistic views in his Romanes Lecture of 1920, "The Idea of Progress"[7] and in his Evening Standard articles. In his Romanes Lecture he said that although mankind's accumulated experience and wonderful discoveries had great value, they did not constitute real progress in human nature itself.

He disapproved of democracy, which he called "an absurdity" and compared it to "the famous occasion when the voice of the people cried, Crucify Him!"[8] He wrote "Human beings are born unequal, and the only persons who have a right to govern their neighbours are those who are competent to do so."[9] He advanced various arguments why women should have fewer voting rights than men, if any.[10][non-primary source needed]

He was also a eugenicist[6] and wrote considerably on the subject. In his book Outspoken Essays, he devotes an entire chapter to this subject. His views included that the state should decide which couples be allowed to have children.[6]

Inge opposed social welfare "on the grounds that it penalized the successful while subsidizing the weak and feckless".[6]

He was also known for his support for nudism.[11] He supported the publishing of Maurice Parmelee's[12] book, The New Gymnosophy: Nudity and the Modern Life,[13] and was critical of town councillors who were insisting that bathers wear full bathing costumes.[14]

Recognition

[edit]He was made a Commander of the Victorian Order (CVO) in 1918 and promoted to Knight Commander (KCVO) in 1930.[4] He received Honorary Doctorates of Divinity from both Oxford and Aberdeen Universities, Honorary Doctorates of Literature from both Durham and Sheffield, and Honorary Doctorates of Laws from both Edinburgh and St Andrews. He was also an honorary fellow of both King's and Jesus Colleges at Cambridge, and of Hertford College at Oxford. In 1921, he was elected as a Fellow of the British Academy (FBA).

Personal life

[edit]

On 3 May 1905, Inge married Mary Catharine ("Kitty"), daughter of Henry Maxwell Spooner,[15] Archdeacon of Maidstone. They had five children:

- William Craufurd Inge (1906–2001)

- Edward Ralph Churton Inge (1907–1980)

- Catharine Mary Inge (1910–1997), married Derek Wigram

- Margaret Paula Inge (1911–1923), died from type 1 diabetes[16]

- Richard Wycliffe Spooner Inge (1915–1941), priest, killed on an RAF training flight[17]

Inge's wife died in 1949.[6]

Inge spent his later life at Brightwell Manor in Brightwell-cum-Sotwell, Oxfordshire, where he died on 26 February 1954, aged 93, five years after his wife.[6]

Publications

[edit]The following bibliography is a selection taken mainly from Adam Fox's biography Dean Inge and his biographical sketch in Crockford's Clerical Directory.

- Society in Rome under the Caesars 1888

- Eton Latin Grammar 1888

- Christian Mysticism (Bampton Lectures) 1899

- Faith 1900

- Contentio Veritatis Essays in Constructive Theology by Six Oxford Tutors (two essays) 1902

- Faith and Knowledge: Sermons 1904

- Light, Life and Love (Selections from the German mystics of the Middle Ages) 1904 also online at Project Gutenberg and CCEL

- Studies of English Mystics 1905

- Truth and Falsehood in Religion (Cambridge Lectures 1906

- Personal Idealism and Mysticism (Paddock Lectures) 1906

- All Saints' Sermons 1907

- Faith and its Psychology (Jowett Lectures) 1909

- Speculum Animae 1911

- The Church and the Age 1912

- The Religious Philosophy of Plotinus and some Modern Philosophies of Religion 1914

- Types of Christian Saintliness 1915

- Christian Mysticism, considered in eight lectures delivered before the University of Oxford (1918)

- The Philosophy of Plotinus (Gifford Lectures) 1918. Online: Volume 1 Volume 2 Print versions: ISBN 1-59244-284-6 (softcover), ISBN 0-8371-0113-1 (hardcover)

- Outspoken Essays I 1919 & II 1922

- The Idea of Progress. Romanes Lecture. 1920.

- The Victorian Age: the Rede Lecture for 1922 1922

- Assessments and Anticipations 1922 (2nd ed. 1929)

- Personal Religion and the Life of Devotion 1924

- Lay Thoughts of a Dean 1926

- The Platonic Tradition in English Religious Thought Hulsean Lectures 1926 ISBN 0-8414-5055-2

- The Church in the World 1927

- Protestantism (London: Ernest Benn Limited, 1927)

- Christian Ethics and Modern Problems 1930

- More Lay Thoughts of a Dean. London and New York: Putnam. 1932.

- Things New and Old 1933

- God and the Astronomers 1933

- The Post Victorians 1933 (Introduction only)

- Vale 1934

- The Gate of Life 1935

- A Rustic Moralist 1937

- Our Present Discontents 1938 ISBN 0-8369-2846-6

- A Pacifist in Trouble 1939 ISBN 0-8369-2192-5

- The Fall of the Idols 1940

- Talks in a Free Country 1942 ISBN 0-8369-2774-5

- Mysticism in Religion 1947 ISBN 0-8371-8953-5

- The End of an Age and Other Essays 1948

- Diary of a Dean 1949

- The Things That Remain edited by W R Matthews 1958

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Inge - Definitions from Dictionary.com

- ^ e.g. in Hensley Henson's diaries: "The Henson Journals". 31 March 1923. Retrieved 23 September 2023.

- ^ a b "Nomination Database". nobelprize.org. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "Inge, William Ralph (IN879WR)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ "Obituary" (PDF). The Hertford College Magazine. No. 42. May 1954. pp. 420–422. Retrieved 23 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Austen n.d.

- ^ Inge 1920.

- ^ "A Cause Lost—and Forgotten". University Bookman. March 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ^ Inge 1932, p. 122.

- ^ Inge 1932, pp. 121–127.

- ^ Shaw 1937, p. 24.

- ^ Parmelee, Maurice (1927). The new gymnosophy: the philosophy of nudity as applied in modern life. F. H. Hitchcock.

- ^ Hirning 2013, p. 276.

- ^ "Dean Inge and The Nudists". Gloucestershire Echo. 17 November 1932. p. 1 col E. Retrieved 2 May 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ See Portraits of Mary Catharine Inge.

- ^ Bliss, Michael (1984). "Resurrections in Toronto: Fact and Myth in the Discovery of Insulin". Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 38 (3): 15–36. JSTOR 20171755.

Paula, the 10-year-old daughter of Dean Inge, the noted Anglican theologian, was less fortunate. The onset of her diabetes was late in 1921. Because the British were operating about a year behind the North Americans, Paula Inge died before good insulin was available. her father consoled himself with the thought that God had given the parents a whole year's grace before taking their daughter.

- ^ "Casualty Details: Inge, Richard Wycliffe Spooner". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

Sources

[edit]- Austen, Timothy (n.d.), "William Ralph Inge", The Gifford Lectures

- Grimley, Matthew (23 September 2004). "Inge, William Ralph (1860–1954)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/34098. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Shaw, Elton Raymond (1937). The Body Taboo: Its Origin, Effect, and Modern Denial. Washington D.C.: Shaw Publishing.

- Hirning, L. Clovis (2013). "Clothing and Nudism". In Albert Ellis; Albert Abarbanel (eds.). The Encyclopædia of Sexual Behaviour. Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4832-2510-4.

Further reading

[edit]- Fox, Adam (1960). Dean Inge. London: J. Murray.

- Helm, Robert Meredith (1962). The Gloomy Dean: the thought of William Ralph Inge. J.F. Blair. ISBN 9780910244275.

- Inge, W. R. (1949). Diary of a Dean: St. Paul's, 1911-1934. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 978-1-258-85399-0.

External links

[edit] Works by or about William Ralph Inge at Wikisource

Works by or about William Ralph Inge at Wikisource- Bibliographic directory from Project Canterbury

- Works by William Ralph Inge at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about William Ralph Inge at the Internet Archive

- Works by or about Dean Inge at the Internet Archive

- Portraits of William Ralph Inge at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Portraits of Mary Catharine Inge at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Recording of Inge speaking

- 1860 births

- 1954 deaths

- 19th-century Christian mystics

- 20th-century Christian mystics

- Alumni of King's College, Cambridge

- Deans of St Paul's

- English Anglicans

- Fellows of Hertford College, Oxford

- Fellows of Jesus College, Cambridge

- Knights Commander of the Royal Victorian Order

- Lady Margaret's Professors of Divinity

- People educated at Eton College

- People from Brightwell-cum-Sotwell

- People from Hambleton District

- Presidents of the Aristotelian Society

- Protestant mystics

- Social nudity advocates

- English eugenicists

- Presidents of the Classical Association