Debrecen

Debrecen | |

|---|---|

| Debrecen Megyei Jogú Város | |

|

Descending, from top: Déri Museum, University of Debrecen, and Protestant Great Church | |

| Nicknames: The Calvinist Rome, Cívis City | |

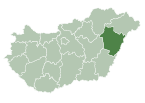

| Coordinates: 47°31′54″N 21°37′28″E / 47.53167°N 21.62444°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Northern Great Plain |

| County | Hajdú-Bihar |

| District | Debrecen |

| Established | 9th century AD |

| City status | 1218 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | László Papp (Fidesz) |

| • Town Notary | Dr Antal Szekeres |

| Area | |

| • City with county rights | 461.25 km2 (178.09 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 3rd in Hungary |

| Elevation | 121 m (396.98 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 151 m (495 ft) |

| Population (2019) | |

| • City with county rights | 202,402[1] |

| • Rank | 2nd in Hungary |

| • Density | 442.09/km2 (1,145.0/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 328,642 (2nd)[2] |

| Demonym(s) | debreceni, cívis |

| Population by ethnicity | |

| • Hungarians | 84.8% |

| • Romani | 0.6% |

| • Germans | 0.6% |

| • Romanians | 0.3% |

| • Other | 2.0% |

| Population by religion | |

| • Calvinist | 24.8% |

| • Roman Catholic | 11.1% |

| • Greek Catholic | 5.1% |

| • Lutheran | 0.4% |

| • Jews | 0.1% |

| • Other | 2.3% |

| • Non-religious | 27.8% |

| • Unknown | 28.4% |

| Time zone | UTC1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 4000 to 4032, 4063 |

| Area code | (+36) 52 |

| Motorways | M35 Motorway |

| NUTS 3 code | HU321 |

| Distance from Budapest | 231 km (144 mi) West |

| International airports | Debrecen (DEB) |

| MPs | List

|

| Website | www |

Debrecen (/ˈdɛbrətsɛn/ DEB-rət-sen, Hungarian: [ˈdɛbrɛt͡sɛn] ; German: Debrezin; Slovak: Debrecín) is Hungary's second-largest city, after Budapest, the regional centre of the Northern Great Plain region and the seat of Hajdú-Bihar County. A city with county rights, it was the largest Hungarian city in the 18th century[3] and it is one of the Hungarian people's most important cultural centres.[4] Debrecen was also the capital city of Hungary during the revolution in 1848–1849. During the revolution, the dethronement of the Habsburg dynasty was declared in the Reformed Great Church. The city also served as the capital of Hungary by the end of World War II in 1944–1945.[4] It is home to the University of Debrecen.

Etymology

[edit]There are at least three narratives of the origin of the city's name. The city is first documented in 1235, as Debrezun. One theory states that the name derives from the Turkic word debresin, which means 'live' or 'move.'[5] Another theory says the name is of Slavic origin and means 'well-esteemed', from Slavic Dьbricinъ or from dobre zliem ("good land").[citation needed] Thirdly and lastly, Professor Šimon Ondruš derived the toponym from Proto-Slavic term *dьbrь (gorge). [6]

The standard Romanian name for the city is Debrețin, however Romanian communities in Hungary use the version Dobrițân.[7]

History

[edit]

The settlement was established after the Hungarian conquest.[4] Debrecen became more important after some of the small villages of the area (Boldogasszonyfalva, Szentlászlófalva) were deserted due to the Mongol invasion of Europe. It experienced rapid development after the middle of the 13th century.[4]

In 1361, Louis I of Hungary granted the citizens of Debrecen the right to choose the town's judge and council. This provided some opportunities for self-government for the town. By the early 16th century, Debrecen was an important market town.[4]

King Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, as part of a treaty with Serbian ruler Stefan Lazarević, gave him the opportunity to rule Debrecen in September 1411.[citation needed] A year after Lazarević's death in 1426, his role was taken over by his successor, Đurađ Branković.[citation needed] Between 1450 and 1507, it was a domain of the Hunyadi family.[4]

During the Ottoman period, being close to the border and having no castle or city walls, Debrecen often found itself in difficult situations and the town was saved only by the diplomatic skills of its leaders. Sometimes the town was protected by the Ottoman Empire, sometimes by the Catholic European rulers or by Francis II Rákóczi, prince of Transylvania. Debrecen later embraced the Protestant Reformation quite early, earning the monikers of "the Calvinist Rome" and "the Geneva of Hungary". At this period the inhabitants of the town were mainly Hungarian Calvinists. Debrecen came under Ottoman control as a sanjak between 1558 and 1693 and orderly bounded to the eyalets of Budin (1541–1596), Eğri (1596–1660) and Varat (1660–1693) as "Debreçin".

In 1693, Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor elevated Debrecen to free royal town status. In 1715, the Roman Catholic Church returned to Debrecen, and the town gave it a place to build a church, allowing the Piarist monks to build the St. Ann's Cathedral. By this time the town was an important cultural, commercial and agricultural centre, and many future scholars and poets attended its Protestant College (a predecessor of today's University of Debrecen and also of Debrecen Reformed Theological University).

In 1849, Debrecen was the capital of Hungary for a short time when the Hungarian revolutionary government fled there from Pest-Buda (modern-day Budapest).[4] In April 1849, the dethronization of Habsburgs (neglected after the fall of the revolution) and the independence of Hungary was proclaimed here by Lajos Kossuth at the Great (Calvinist) Church (Nagytemplom in Hungarian.) The last battle of the war of independence was also close to Debrecen. The Russians, allied to Habsburgs, defeated the Hungarian army close to the western part of the town.

After the war, Debrecen slowly began to prosper again. In 1857, the railway line between Budapest and Debrecen was completed, and Debrecen soon became a railway junction. New schools, hospitals, churches, factories, and mills were built, banks and insurance companies settled in the city. The appearance of the city began to change too: with new, taller buildings, parks and villas, it no longer resembled a provincial town and began to look like a modern city. In 1884, Debrecen became the first Hungarian city to have a steam tramway.

After World War I, Hungary lost a considerable portion of its eastern territory to Romania, and Debrecen once again became situated close to the border of the country. It was occupied by the Romanian army for a short time in 1919. Tourism provided a way for the city to begin to prosper again. Many buildings (among them an indoor swimming pool and Hungary's first stadium) were built in the central park, the Nagyerdő ("Big Forest"), providing recreational facilities. The building of the university was completed. Hortobágy, a large pasture owned by the city, became a tourist attraction.

During World War II, Debrecen was almost completely destroyed, 70% of the buildings suffered damage, 50% of them were completely destroyed. A major battle involving combined arms, including several hundred tanks (Battle of Debrecen), occurred near the city in October 1944. Debrecen was captured by Soviet troops of the 2nd Ukrainian Front on 20 October. After 1944, the reconstruction began and Debrecen became the capital of Hungary for a short time once again.[4] The citizens began to rebuild their city, trying to restore its pre-war status, but the new, Communist government of Hungary had other plans. The institutions and estates of the city were taken into public ownership, private property was taken away. This forced change of the old system brought new losses to Debrecen; half of its area was annexed to nearby towns, and the city also lost its rights over Hortobágy. In 1952, two new villages – Ebes and Nagyhegyes – were formed from former parts of Debrecen, while in 1981, the nearby village Józsa was annexed to the city.

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 45,132 | — |

| 1880 | 50,320 | +11.5% |

| 1890 | 56,246 | +11.8% |

| 1900 | 73,878 | +31.3% |

| 1910 | 90,764 | +22.9% |

| 1920 | 101,543 | +11.9% |

| 1930 | 116,013 | +14.3% |

| 1941 | 124,148 | +7.0% |

| 1949 | 115,399 | −7.0% |

| 1960 | 134,930 | +16.9% |

| 1970 | 167,860 | +24.4% |

| 1980 | 198,195 | +18.1% |

| 1990 | 212,235 | +7.1% |

| 2001 | 211,034 | −0.6% |

| 2011 | 211,320 | +0.1% |

| 2022 | 199,858 | −5.4% |

| Source: [8][9] | ||

Languages

[edit]According to the 2011 census, the total population of Debrecen were 211,320, of whom 209,782 people (99.3%) spoke Hungarian. 49,909 (23.6%) also knew English, 22,454 (10.6%) German, and 5,416 (2.6%) could speak Russian.[10]

Ethnic groups

[edit]According to the 2011 census, there were 177,435 (84.0%) Hungarians, 1,305 (0.6%) Romani, 554 (0.3%) Germans and 504 (0.2%) Romanians in Debrecen. 31,931 people (15.1% of the total population) did not declare their ethnicity. Excluding these people Hungarians made up 98.9% of the total population. In Hungary people can declare more than one ethnicity, so the sum of ethnicities is higher than the total population.[10][11]

| Largest groups of foreign residents | |

| Nationality | Population (2011) |

|---|---|

| 1,303 | |

| 739 | |

| 305 | |

| 262 | |

| 166 | |

| 126 | |

| 98 | |

| 98 | |

Religion

[edit]Religion in Debrecen (2022)[12]

According to the 2011 census, there were 52,459 (24.8%) Hungarian Reformed (Calvinist), 23,413 (11.1%) Latin Catholic, 10,762 (5.1%) Greek Catholic, 899 (0.4%) Baptist, 885 (0.4%) Jehovah's Witnesses, and 812 (0.4%) Lutheran in Debrecen. 54,909 people (26.0%) were irreligious, 3,877 (1.8%) atheist, while 59,955 people (28.4%) did not declare their religion.[10]

Reformed Church in Debrecen

[edit]

From the 16th century, the Reformation took roots in the city; first Lutheranism, then Calvin's teachings become predominant. From 1551, the Calvinist government of the city forbade Catholics from moving to Debrecen. Catholic churches were taken over by the Calvinist church. The Catholic faith vanished from the city until 1715 when it regained a church. Several Calvinist church leaders like Peter Melius Juhasz who translated the Genevan Psalms lived and worked here. In 1567, a synod was formed in the city when the Second Helvetic Confession was adopted. Famous Calvinist colleges and schools were formed. Nickname of Debrecen commonly used in Hungary is the Calvinist Rome or the Geneva of Hungary because of the great percentage of the Calvinist faith in the city as well as the Calvinist church has significant influence in the city and the region. Debrecen is also home to the Reformed Theological University of Debrecen (Debreceni Református Hittudományi Egyetem),[13] founded in 1538 and was the only Calvinist theological institute in the country permitted to function during the communist rule.[14][15][16]

The Hungarian Reformed Church has about 20 congregations in Debrecen, including the famous Reformed Great Church of Debrecen, which can easily accommodate about 5000 people (with 3000 seats).[17]

Jewish community

[edit]

Jews were first allowed to settle in Debrecen in 1814, with an initial population count of 118 men within 4 years. Twenty years later, they were allowed to purchase land and homes. By 1919, they consisted 10% of the population (with over 10,000 community members listed) and owned almost half of the large properties in and around the town.[18]

The Hungarian antisemitic laws of 1938 caused many businesses to close, and in 1939 many Jews were enslaved and sent to Ukraine, where many died in minefields.[18]

In 1940, the Germans estimated that 12,000 Jews were left in the town. In 1941, Jews of Galician and Polish origin were expelled, reducing the number of Jews to 9142. In 1942, more Jews were drafted into the Hungarian forced labor groups and sent to Ukraine.

German forces entered the city on 20 March 1944, (Two and a half weeks before Passover) ordering a Judenrat (Jewish Council) headed by Rabbi Pal (Meir) Weisz, and a Jewish police squad was formed, headed by former army captain Bela Lusztbaum. On 30 March 1944, (a week before Passover) the Jews were ordered to wear the Yellow star of David. Jewish cars were confiscated and phone lines cut. During the Passover week, many Jewish dignitaries were taken to a nearby prison camp, eventually reaching the number of 300 prisoners. A week later all Jewish stores were closed, and a public book-burning of Jewish books was presided over by the antisemitic newspaper editor Mihaly Kalosvari Borska. [citation needed]

An order to erect a ghetto was issued on 28 April 1944, in the name of the town mayor Sandor Kolscey, who opposed the act, and was ousted by the Germans. Jews were forced to build the Ghetto walls, finishing it within less than a month on 15 May 1944.

On 7 June 1944, all movement in or out of the Ghetto was prohibited and a week later all Debrecen Jews were deported to the nearby Serly brickyards, and stripped of their belongings, joining Jews from other areas.[19][20]

Ten families of prominent Jews, including those of Rabbi Weisz and orthodox chief Rabbi Strasser, along with the heads of the Zionist (non orthodox) movement joined the Kasztner train. (According to some sources, the Strasshoff camps were filled with Jews for negotiations in case the Germans could receive something for releasing these Jews, among them 6841 from Debrecen.) 298 of these Debrecen Jews were shot by the SS in Bavaria, after being told they would reach Theresienstadt. Some young Debrecen Jews escaped the town, led by the high school principal Adoniyahu Billitzer and reached Budapest, joining resistance movements and partisans.[19]

Most of the remaining Debrecen Jews were deported to Auschwitz, reaching there on 3 July 1944. Debrecen was occupied by the Soviet Army on 20 October 1944. Some 4,000 Jews of Debrecen and its surroundings survived the war, creating a community of 4,640 in 1946 – the largest in the region. About 400 of those moved to Israel, and many others moved to the west by 1970, with 1,200 Jews left in the town, using two synagogues, one of them established before World War I.[21]

Climate

[edit]Debrecen, typically for its Central European location, has a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfb). The annual average temperature is 11.0 °C (51.8 °F), the hottest month in July is 21.9 °C (71.4 °F), and the coldest month is −0.8 °C (30.6 °F) in January. The annual precipitation is 542.7 millimetres (21.37 in), of which July is the wettest with 67.7 millimetres (2.67 in), while January is the driest with only 24.3 millimetres (0.96 in).

| Climate data for Debrecen, 1991−2020 normals, extremes 1901-2022 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.4 (59.7) |

19.1 (66.4) |

26.4 (79.5) |

33.6 (92.5) |

33.4 (92.1) |

37.4 (99.3) |

38.7 (101.7) |

39.2 (102.6) |

36.4 (97.5) |

29.5 (85.1) |

25.5 (77.9) |

17.4 (63.3) |

39.2 (102.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 2.3 (36.1) |

5.0 (41.0) |

10.9 (51.6) |

17.7 (63.9) |

22.5 (72.5) |

26.0 (78.8) |

27.8 (82.0) |

28.1 (82.6) |

22.6 (72.7) |

16.6 (61.9) |

9.8 (49.6) |

3.2 (37.8) |

16.0 (60.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −0.8 (30.6) |

0.9 (33.6) |

5.8 (42.4) |

11.9 (53.4) |

16.8 (62.2) |

20.3 (68.5) |

21.9 (71.4) |

21.8 (71.2) |

16.5 (61.7) |

11.0 (51.8) |

5.5 (41.9) |

0.4 (32.7) |

11.0 (51.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −3.6 (25.5) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

1.2 (34.2) |

6.1 (43.0) |

10.8 (51.4) |

14.6 (58.3) |

16.0 (60.8) |

15.7 (60.3) |

11.2 (52.2) |

6.2 (43.2) |

2.1 (35.8) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

6.3 (43.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −30.2 (−22.4) |

−26.0 (−14.8) |

−17.8 (0.0) |

−7.1 (19.2) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

5.2 (41.4) |

2.7 (36.9) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

−14.9 (5.2) |

−19.0 (−2.2) |

−28.0 (−18.4) |

−30.2 (−22.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 24.3 (0.96) |

32.2 (1.27) |

30.0 (1.18) |

45.1 (1.78) |

59.3 (2.33) |

66.8 (2.63) |

67.7 (2.67) |

46.4 (1.83) |

47.3 (1.86) |

41.1 (1.62) |

40.5 (1.59) |

42.0 (1.65) |

542.7 (21.37) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 6.1 | 6.6 | 6.1 | 6.8 | 8.4 | 8.2 | 7.6 | 6.0 | 6.6 | 6.2 | 6.9 | 7.1 | 82.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 84.4 | 78.8 | 68.6 | 62.2 | 65.1 | 66.5 | 65.9 | 64.2 | 69.7 | 77.0 | 83.7 | 85.5 | 72.6 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 57.6 | 85.0 | 146.8 | 190.3 | 251.4 | 266.4 | 295.3 | 274.3 | 201.7 | 155.1 | 72.2 | 47.0 | 2,043.1 |

| Source 1: HMS[22] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Ogimet(June record high),[23] NOAA[24] | |||||||||||||

Culture

[edit]

Mainly thanks to the Reformation and the prestigious Reformed College of Debrecen, founded in 1538, Debrecen has been the intellectual and cultural centre of the surrounding area since the 16th century.[25] The College formed into a full-scale university in 1912, and its intellectual life developed a sphere of influence between Eger and Oradea (Hu: Nagyvárad, now in Romania). In 1949–1950, several departments of the university were shut down, due to Communist takeover, with many students and teachers being expelled. During the decades of the socialist regime, Debrecen had three separate universities: the Kossuth Lajos University of Sciences (KLTE) was the bearer of the College's traditions with its arts and natural science faculties; the Medical University of Debrecen (DOTE) was the main medical school of Eastern Hungary; and the Debrecen University of Agriculture (DATE) was one of the two major agricultural universities of the country besides Gödöllő. The three entities formed the current University of Debrecen in 2000, with several new faculties being formed since the 1990s from the Faculty of Law to the newest addition of the Faculty of Informatics. Its main building, which now almost unanimously belongs to the Faculty of Arts, is still widely recognized work of architecture (mostly thanks to its main building). The university is the largest university in Hungary, has more than 100 departments and is a major research facility in Europe.[26] The university is well known for the cactus research laboratory in the botanic gardens behind the main building.

In the second half of the 19th century, the Debrecen press attracted several notable figures to the city. Endre Ady, Gyula Krúdy, and Árpád Tóth all began their journalistic careers in Debrecen. Prominent literary figures from the city have included Magda Szabó, and Gábor Oláh. One of Hungary's best known poets, Mihály Csokonai Vitéz, was born and lived in the city. The city's theatre, built in 1865, was named in his honour in 1916, but can trace its roots back to the National Theatre Company founded in Debrecen in 1789, which at first gave performances in the carthouse of an inn. Celebrated actress Lujza Blaha is among those to have performed there.[27]

Debrecen is home to Tankcsapda, one of Hungary's most successful rock bands.[citation needed] There is also a rock school in the city which offers training and mentoring to young musicians. Classic media in the city include the newspaper Napló, two TV channels, a range of local radio stations and several companies and associations producing media material.

Debrecen is the site of an important choral competition, the Béla Bartók International Choir Competition, and is a member city of the European Grand Prix for Choral Singing. Every August the city plays host to a flower festival.

Economy

[edit]The development of Debrecen is mainly financed by agricultural, health and educational enterprises. The city is the main center of shopping centers in Eastern Hungary. The Forum Debrecen is the largest shopping center in the region. Debrecen is one of the most developed cities in Hungary, the regional center of international companies such as National Instruments, IT Services Hungary, BT, Continental, BMW, CATL and Healthcare Manufacturers (Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. and Gedeon Richter Plc.).

Location

[edit]

Debrecen is located on the Great Hungarian Plain, 220 km (137 mi) east of Budapest. Situated nearby is the Hortobágy National Park.

Transport

[edit]The city used to be somewhat isolated from Budapest, Hungary's main transport hub. However, the completion of the M35 motorway means Budapest can now be reached in under two hours. Debrecen Airport (the second largest in Hungary) has recently undergone modernisation in order to be able to handle more international flights, although almost all flights to and from Hungary still use Budapest's Ferihegy Airport (now called Budapest Ferenc Liszt International Airport). Cities that can be reached from the Debrecen Airport include Brussels, Eindhoven, London, Malmö, Milan, Tel Aviv, Moscow and Paris. There have also been improvements to some parts of the railway between the capital and Debrecen as part of Hungary's mainly EU-funded National Development Plan for 2004 to 2006. [citation needed]

There are many railway stations in Debrecen, the most significant is the main station of Debrecen, in addition other smaller stations exist, these include Debrecen-Csapókert, Debrecen-Kondoros, Debrecen-Szabadságtelep and Tócóvölgy.[28]

Debrecen's proximity to Ukraine, Slovakia and Romania enables it to develop as an important trade centre and transport hub for the wider international region.

Local transport in the city consists of buses, trolleybuses, and trams. There are two tram lines, five trolleybus lines, and 60 bus lines. It is provided by the DKV (Debreceni Közlekedési Vállalat, or Transport Company of Debrecen). Nearby towns and villages are linked to the city by Hajdú Volán bus services.

Sports

[edit]The city's most famous association football club is Debreceni VSC[29] which won the Nemzeti Bajnokság I seven times,[30] the last one in 2014. Debreceni VSC also known at international level since they reached the 2009-10 UEFA Champions League group stage[31] and the 2010-11 UEFA Europa League group stage. The club's newly built stadium was opened in 2014, where the club could celebrate their seventh title by winning the 2014-15 Nemzeti Bajnokság I. The stadium is also the occasional home of the Hungary national football team. The team hosted Denmark in 2014 and Lithuania in 2015.

The city had other association football clubs competing in the Nemzeti Bajnokság I. One of them was Bocskai FC who could also won the Magyar Kupa once in 1930. The other club from the city was Dózsa MaDISz TE who competed in the 1945-46 Nemzeti Bajnokság I.

The city has hosted several international sporting events in recent years, such as the second World Youth Championships in Athletics in July 2001 and the first IAAF World Road Running Championships in October 2006. The 2007 European SC Swimming Championships and World Artistic Gymnastics Championships of 2002 also took place in Debrecen. Most recently, the city hosted the 19th FAI World Hot Air Balloon Championship[32] in October 2010. In 2012, Debrecen hosted the 31st LEN European Swimming Championships.

The Debrecen Speedway team race at the Perényi Pál Salakmotor Stadion in the south of the city. The stadium also regularly hosts international events including qualifying rounds of the Speedway World Cup and the Speedway European Championship.[33][34]

Association football

[edit]- Debreceni VSC (competing in the Nemzeti Bajnokság I)

- Bocskai FC (defunct)

- Dózsa MaDISz TE (defunct)

- Debreceni EAC

Main sights

[edit]- City Downtown

- Reformed Great Church (Nagytemplom)

- City Park (Nagyerdő) and spa

- Déri Museum (art collection including paintings of Mihály Munkácsy; also has a collection of Ancient Egyptian artifacts, and weapons from Europe, the Middle East and Far East)[35]

- Flower Carnival of Debrecen[36] held on 20 August every year

- "Hortobágy" mill

- Nagyerdei Stadion (the home football stadium of the association football club Debreceni VSC)

- Ravatalozó (cemetery)

- Csokonai theatre[37]

-

Malom Hotel (former „Hortobágy” mill)

-

Ravatalozó in Art Nouveau architectural style

-

Heritage building in (Nagyerdő)

-

Déri Museum

-

Csokonai theatre

Politics

[edit]The current mayor of Debrecen is Dr. László Papp (Fidesz-KDNP).

The local Municipal Assembly, elected at the 2019 local government elections, is made up of 33 members (1 Mayor, 23 Individual constituencies MEPs and 9 Compensation List MEPs) divided into this political parties and alliances:[38]

| Party | Seats | Current Municipal Assembly | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fidesz-KDNP | 24 | M | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DK-MSZP-Dialogue-Solidarity | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Momentum-Jobbik-LMP | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Civil Forum Debrecen | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

List of mayors

[edit]List of City Mayors from 1990:[39]

| Member | Party | Term of office | |

|---|---|---|---|

| József Hevessy | SZDSZ | 1990–1998 | |

| Lajos Kósa | Fidesz (-KDNP) | 1998–2014 | |

| László Papp | Fidesz-KDNP | 2014– | |

Notable people

[edit]Born in Debrecen

[edit]- Emma Adler (1858–1935), writer

- Lorenzo Alvary (1909–1996), operatic bass

- Ferenc Barnás (born 1959), novelist

- Zsolt Baumgartner (born 1981), first Hungarian Formula One driver

- Mihály Csokonai Vitéz (1773–1805), poet

- Sari Dienes (1898–1992), artist

- Éva Fahidi (1925–2023), Auschwitz survivor

- Mihály Fazekas (1766–1828), writer

- Mihály Flaskay (born 1982), breaststroke swimmer

- Nóra Görbe, (born 1956), actress, singer and pop icon

- Meshulam Gross (1863–1947), Hungarian-American entrepreneur

- Boglárka Kapás (born 1993), Swimmer, 2019 World Champion - 200 m butterfly, 2016 Olympic bronze Medalist - 800 m freestyle

- István Kardos (1891-1975), conductor and composer[40]

- George Karpati (1934–2009), physician, neurologist, surgeon, teacher, author

- Rivka Keren (born 1946), Israeli writer

- Vivien Keszthelyi (born 2000), racing driver

- Miklós Kocsár (1933-2019), composer

- Orsi Kocsis (born 1984), fashion, glamour and art nude model

- Imre Lakatos (1922–1974), philosopher of mathematics and of science

- Paul László (1900–1993), architect

- Gábor Máthé (born 1985), tennis Deaflympics champion

- Mihály Nagy (born 1937) high school teacher; research teacher; university doctor; mineralogist; meteorite researcher

- Judah Samet (1938-2022), Hungarian-American businessman, speaker, and Holocaust survivor

- Magda Szabó (1917–2007), writer[41]

- Borbala Biro (born 1957), biologist and agricultural scientist

- József Váradi (born 1965), CEO of Wizz Air

- Chaim Michael Dov Weissmandl (1903–1957), rabbi and Holocaust activist

Lived in Debrecen

[edit]- Endre Ady (1877–1919), poet

- Julia Bathory (1901–2000), glass artist

- Rudolf Charousek (1873–1812? 1873 until grade 4), World Champion chess master

- Géza Hofi (1936–2002), stand-up comedian

- Albert Kardos (1861-1945), literary scholar, linguist, pedagogue and publicist[42]

- Andrew Karpati Kennedy, author and literary critic

- Sándor Petőfi (1823–1849), poet

- Alfréd Rényi (1921–1970), mathematician

- Éva Risztov (born 1985), Olympic champion swimmer

- Moshe Stern (1914–1997), Rabbi and authority on Jewish law

- Sándor Szalay (physicist) (1909–1987), physicist, founder of ATOMKI

- Árpád Tóth (1886–1928), poet

Died in Debrecen

[edit]- Pierre-Octave Ferroud (1900-1936), French composer

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]

Košice, Slovak Republic

Košice, Slovak Republic Brno, Czech Republic

Brno, Czech Republic Cattolica, Italy

Cattolica, Italy Jyväskylä, Finland

Jyväskylä, Finland Klaipėda, Lithuania

Klaipėda, Lithuania Limerick County, Ireland

Limerick County, Ireland Lublin, Poland

Lublin, Poland New Brunswick, United States

New Brunswick, United States Oradea, Romania

Oradea, Romania Paderborn, Germany

Paderborn, Germany Patras, Greece

Patras, Greece Rishon LeZion, Israel

Rishon LeZion, Israel Saint Petersburg, Russia

Saint Petersburg, Russia Setúbal, Portugal

Setúbal, Portugal Shumen, Bulgaria

Shumen, Bulgaria Syktyvkar, Russia

Syktyvkar, Russia Taitung City, Taiwan

Taitung City, Taiwan Toluca, Mexico

Toluca, Mexico Tongliao, China

Tongliao, China

See also

[edit]Debrecen cuisine

[edit]- Debrecener – a pork sausage

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Detailed Gazetteer of Hungary". www.ksh.hu. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ OECD - FUNCTIONAL URBAN AREAS IN OECD COUNTRIES: HUNGARY

- ^ Dezső Danyi-Zoltán Dávid: Az első magyarországi népszámlálás (1784-1787)/The first census in Hungary (1784-1787), Hungarian Central Statistical Office, Budapest, 1960

- ^ a b c d e f g h Antal Papp: Magyarország (Hungary), Panoráma, Budapest, 1982, ISBN 963 243 241 X, p. 860, pp. 463-477

- ^ "History of Debrecen (Hungarian)". Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ Ondruš, Šimon. Odtajnené trezory 2. Martin: Matica Slovenská (2002). p.190 ISBN 80-7090-659-6

- ^ Rosenberg, Mátyás (2021). "The language of Boyash communities in Central and Eastern Hungary". In Sorescu-Marinković, Annemarie; Kahl, Thede; Sikimić, Biljana (eds.). Boyash Studies: Researching "Our People". Forum: Rumänien. Frank & Timme Verlag. p. 252. ISBN 9783732906949.

- ^ népesség.com, [1]

- ^ "Census database - Hungarian Central Statistical Office".

- ^ a b c Hungarian census 2011 Területi adatok - Hajdú-Bihar megye / 3.1.4.2 A népesség nyelvismeret, korcsoport és nemek szerint (population by spoken language), 3.1.6.1 A népesség a nmezetiségi hovatartozást befolyásoló tényezők szerint (population by ethnicity), 3.1.7.1 A népesség vallás, felekezet és fontosabb demográfiai ismérvek szerint (population by religion), 4.1.1.1 A népesség számának alakulása, terület, népsűrűség (population change 1870-2011, territory and population density) (Hungarian)

- ^ "Hungarian census 2011 - final data and methodology" (PDF). Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ "Népszámlálási adatbázis – Központi Statisztikai Hivatal". Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ "DRHE". Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ "Egyetemünk – DRHE". Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ "A kerület története - Egyházkerület - Tiszántúli Református Egyházkerület". Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ "Reformatus.hu | History of the RCH". regi.reformatus.hu. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ "Debreceni Református Egyházmegye". Debreceni Református Egyházmegye. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ a b Debrecen Kehilla book, pp. 12-14

- ^ a b The Encyclopedia of Jewish Life Before and During the Holocaust On the Hajdúböszörmény jail camp

- ^ "Judah Samet: Dodging Bullets Again". 28 April 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ Eugene KATZ. "KehilaLinks on Debrecen". kehilalinks.jewishgen.org. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "Climate data for Debrecen 1901-2000". Hungarian Meteorological Service. Archived from the original on 24 February 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- ^ "12882: Debrecen (Hungary)". ogimet.com. OGIMET. 30 June 2022. Archived from the original on 21 September 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ "WMO climate normals for 1991-2020: Debrecen-12882". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original (CSV) on 21 September 2023. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ "University of Debrecen Medical School". eu-medstudy.com. Archived from the original on 21 February 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ "History of the University | Debreceni Egyetem". Unideb.hu. 1 January 2000. Archived from the original on 4 March 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ^ "Csokonai Színház". Csokonai Színház. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ "MÁV-START :: ELVIRA - belföldi vasúti utastájékoztatás". Elvira.mav-start.hu. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ^ "Debreceni VSC". UEFA. 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Hungarian League winners". The Rec Sport Soccer Statistics Foundation. 15 July 2014.

- ^ "UEFA Champions League 2009-10: Clubs". UEFA. 15 July 2014.

- ^ 2010worldballoons.com Archived 15 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Debrecen, Hajdú Volán Stadion". Magyar Futball. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- ^ "DEBRECEN - Hungary". Speedway Plus. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- ^ Visit Debrecen. Deri Museum

- ^ "debreceniviragkarneval.hu". debreceniviragkarneval.hu. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ^ "Csokonai Theatre | Sightseeing | Debrecen".

- ^ "Városi közgyűlés tagjai 2019-2024 - Debrecen (Hajdú-Bihar megye)". valasztas.hu. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ "Debrecen vezetői 1271-től". debrecen.hu.

- ^ "Kardos, István | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ "The City of Literature: The Writers and Poets of Debrecen".

- ^ "Kardos, Albert". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ "Testvérvárosok". debrecen.hu (in Hungarian). Debrecen. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]External links

[edit]- Official website in Hungarian and English

- Official website for expats in English

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. VII (9th ed.). 1878. p. 15.

- Debrecen Travel Guide

- Debrecen at funiq.hu