Secret Gospel of Mark

It has been suggested that parts of this page be moved into Mar Saba letter. (Discuss) (February 2022) |

| Part of a series on |

| New Testament apocrypha |

|---|

|

|

|

The Secret Gospel of Mark or the Mystic Gospel of Mark[1] (Biblical Greek: τοῦ Μάρκου τὸ μυστικὸν εὐαγγέλιον, romanized: tou Markou to mystikon euangelion),[a][3] also the Longer Gospel of Mark,[4][5] is a putative longer and secret or mystic version of the Gospel of Mark. The gospel is mentioned exclusively in the Mar Saba letter, a document of disputed authenticity, which is said to have been written by Clement of Alexandria (c. AD 150–215). This letter, in turn, is preserved only in photographs of a Greek handwritten copy seemingly transcribed in the 18th century into the endpapers of a 17th-century printed edition of the works of Ignatius of Antioch.[b][8][9][10] Some scholars suggest that the letter implies that Jesus was involved in homosexual activity, although this interpretation is contested.

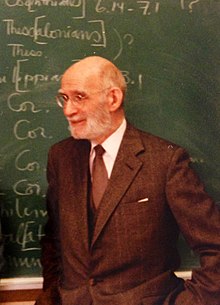

In 1958, Morton Smith, a professor of ancient history at Columbia University, found a previously unknown letter of Clement of Alexandria in the monastery of Mar Saba situated 20 kilometres (12 miles) south-east of Jerusalem.[11] He made a formal announcement of the discovery in 1960[12] and published his study of the text in 1973.[10][13] The original manuscript was subsequently transferred to the library of the Greek Orthodox Church in Jerusalem, and sometime after 1990, it was lost.[14][15] Further research has relied upon photographs and copies, including those made by Smith himself.[16]

In the letter, addressed to one otherwise unknown Theodore (Theodoros),[17][18] Clement says that "when Peter died a martyr, Mark [i.e. Mark the Evangelist] came over to Alexandria, bringing both his own notes and those of Peter, from which he transferred to his former book [i.e. the Gospel of Mark] the things suitable to whatever makes for progress toward knowledge."[19] He further says that Mark left this extended version, known today as the Secret Gospel of Mark, "to the church in Alexandria, where it even yet is most carefully guarded, being read only to those who are being initiated into the great mysteries."[19][20][21] Clement quotes two passages from this Secret Gospel of Mark, where Jesus in the longer passage is said to have raised a rich young man from the dead in Bethany,[22] a story which shares many similarities with the story of the raising of Lazarus in the Gospel of John.[23][24][25]

The revelation of the letter caused a sensation at the time but was soon met with accusations of forgery and misrepresentation.[26] There is no consensus on the authenticity of the letter among either patristic Clement scholars or biblical scholars.[27][28][29][30][31] As the text is made up of two texts, a handful of possibilities exist: both may be authentic or inauthentic, or one may be authentic and the other inauthentic.[32] Those who think the letter is a forgery mostly think it is a modern forgery, with Smith being denounced the most often as the perpetrator.[32] If the letter is a modern forgery, the excerpts from the Secret Gospel of Mark would also be forgeries.[32] Some accept the letter as genuine but do not believe in Clement's account, and instead argue that the gospel is a 2nd-century Gnostic pastiche.[33][34] Others think Clement's information is accurate and that the secret gospel is a second edition of the Gospel of Mark expanded by Mark himself.[35] Still others see the Secret Gospel of Mark as the original gospel which predates the canonical Gospel of Mark,[36][37] and where canonical Mark is the result of the Secret Mark passages quoted by Clement and other passages being removed, either by Mark himself or by someone else at a later stage.[38][39]

There is an ongoing controversy surrounding the authenticity of the Mar Saba letter.[40] The scholarly community is divided as to the authenticity, and the debate on Secret Mark therefore in a state of stalemate,[41][32][26] although the debate continues.[42]

Discovery

[edit]Smith's discovery of the Mar Saba letter

[edit]

During a trip to Jordan, Israel, Turkey, and Greece in the summer of 1958 "hunting for collections of manuscripts",[44] Morton Smith also visited the Greek Orthodox monastery of Mar Saba[45] situated between Jerusalem and the Dead Sea.[46] He had been granted permission by the Patriarch Benedict I of Jerusalem to stay there for three weeks and study its manuscripts.[47][43] It was while cataloguing documents in the tower library of Mar Saba, he later reported, that he discovered a previously unknown letter written by Clement of Alexandria in which Clement quoted two passages from a likewise previously unknown longer version of the Gospel of Mark, which Smith later named the "Secret Gospel of Mark".[7] The text of the letter was handwritten into the endpapers of Isaac Vossius' 1646 printed edition of the works of Ignatius of Antioch.[b][7][6][8][9] This letter is referred to by many names, including the Mar Saba letter, the Clement letter, the Letter to Theodore and Clement's letter to Theodore.[48][49][50][51][52][53]

As the book was "the property of the Greek Patriarchate", Smith just took some black-and-white photographs of the letter and left the book where he had found it, in the tower library.[10] Smith realized, that if he were to authenticate the letter, he needed to share its contents with other scholars. In December 1958, to ensure that no one would reveal its content prematurely, he submitted a transcription of the letter with a preliminary translation to the Library of Congress.[c][55]

After having spent two years comparing the style, vocabulary, and ideas of Clement's letter to Theodore with the undisputed writings of Clement of Alexandria[56][57][10][58] and having consulted a number of paleographic experts who dated the handwriting to the eighteenth century,[59][60] Smith felt confident enough about its authenticity and so announced his discovery at the annual meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature in December 1960.[10][61][d] In the following years, he made a thorough study of Mark, Clement and the letter's background and relationship to early Christianity,[56] during which time he consulted many experts in the relevant fields. In 1966 he had basically completed his study, but the result in the form of the scholarly book Clement of Alexandria and a Secret Gospel of Mark[63] was not published until 1973 due to seven years of delay "in the production stage".[10][64] In the book, Smith published a set of black-and-white photographs of the text.[65] Earlier the same year he also published a second book for the popular audience.[66][67][68]

Subsequent history of the manuscript

[edit]For many years it was thought that only Smith had seen the manuscript.[69] However, in 2003 Guy Stroumsa reported that he and a group of other scholars saw it in 1976. Stroumsa, along with the late Hebrew University professors David Flusser and Shlomo Pines and Greek Orthodox Archimandrite Meliton, went to Mar Saba to look for the book. With the help of a Mar Saba monk, they relocated it where Smith presumably had left it 18 years earlier, and with "Clement's letter written on the blank pages at the end of the book".[70] Stroumsa, Meliton, and company determined that the manuscript might be safer in Jerusalem than in Mar Saba. They took the book back with them, and Meliton subsequently brought it to the Patriarchate library. The group looked into having the ink tested but the only entity in the area with such technology was the Jerusalem police. Meliton did not want to leave the manuscript with the police, so no test was taken.[71][72] Stroumsa published his account upon learning that he was the "last [known] living Western scholar" to have seen the letter.[71][14][73]

Subsequent research has uncovered more about the manuscript. Around 1977,[74] librarian Father Kallistos Dourvas removed the two pages containing the text from the book for the purpose of photographing and re-cataloguing them.[75] However, the re-cataloguing obviously never happened.[15] Dourvas later told Charles W. Hedrick and Nikolaos Olympiou that the pages were then kept separately alongside the book at least until his retirement in 1990.[76] Sometime after that, however, the pages went missing, and various attempts to locate them since that time have been unsuccessful.[72] Olympiou suggests that individuals at the Patriarchate Library may be withholding the pages due to Morton Smith's homoerotic interpretation of the text,[77][78][79] or the pages could have been destroyed or misplaced.[75] Kallistos Dourvas gave color photographs of the manuscript to Olympiou, and Hedrick and Olympiou published them in The Fourth R in 2000.[14][15]

These color photographs were made in 1983 by Dourvas at a photo studio. But this was arranged and paid for by Quentin Quesnell. In June 1983,[80] Quesnell was given permission to study the manuscript at the library for several days during a three-week period[81] under the supervision of Dourvas.[82] Quesnell was "the first scholar to make a formal case that the Mar Saba document might be a forgery" and he was "extremely critical" of Smith, especially for not making the document available to his peers and for providing such low-quality photographs.[83][84] Yet, Quesnell did not tell his peers that he had also examined the manuscript and did not reveal that he already had these high-quality color photographs of the letter at home in 1983.[85] Hedrick and Olympiou were not aware of this when they published, in 2000,[86] copies of the same photographs that Dourvas had kept himself.[87] The scholarly community was unaware of Quesnell's visit until 2007 when Adela Yarbro Collins briefly mentioned that he was allowed to look at the manuscript in the early 1980s.[88][85] A couple of years after Quesnell's death in 2012, scholars were given access to the notes from his trip to Jerusalem.[89] They show that Quesnell at first was confident that he would be able to establish that the document was a forgery.[90] However, when he found something he thought was suspicious, Dourvas (who was confident that it was authentic 18th-century handwriting)[91] would present other 18th-century handwriting with similar characteristics.[90] Quesnell admitted that since "they're not all forgeries" it would not be as easy to prove that the text is a forgery as he had expected. Eventually, he gave up his attempts and wrote that experts had to be consulted.[92]

As of 2019[update], the manuscript's whereabouts are unknown,[93] and it is documented only in the two sets of photographs: Smith's black-and-white set from 1958 and the color set from 1983.[82] The ink and fiber were never subjected to examination.[94]

Content according to Clement's letter

[edit]

| Morton Smith’s photo of the last page of Voss’ printed book and the first page of the Letter to Theodore manuscript. Morton Smith Papers, box 1/7, and Saul Liebermann Papers, box 1/11. |

|---|

The Mar Saba letter is addressed to one Theodore (Biblical Greek: Θεόδωρος, romanized: Theodoros),[18] who seems to have asked if there is a gospel of Mark in which the words "naked man with naked man" (Biblical Greek: γυμνὸς γυμνῷ, romanized: gymnos gymnō) and "other things" are present.[96] Clement confirms that Mark wrote a second, longer, mystic and more spiritual version of his gospel, and that this gospel was "very securely kept" in the Alexandrian church, but that it contained no such words.[96] Clement accuses the heterodox teacher Carpocrates for having obtained a copy by deceit and then polluted it with "utterly shameless lies". To refute the teachings of the gnostic sect of Carpocratians, known for their sexual libertinism,[97][98] and to show that these words were absent in the true Secret Gospel of Mark, Clement quoted two passages from it.[99][38]

There were accordingly three versions of Mark known to Clement, Original Mark, Secret Mark, and Carpocratian Mark.[21] The Secret Gospel of Mark is described as a second "more spiritual" version of the Gospel of Mark composed by the evangelist himself.[25] The name derives from Smith's translation of the phrase "mystikon euangelion". However, Clement simply refers to the gospel as written by Mark. To distinguish between the longer and shorter versions of Mark's gospel, he twice refers to the non-canonical gospel as a mystikon euangelion[100] (either a secret gospel whose existence was concealed or a mystic gospel "pertaining to the mysteries"[101] with concealed meanings),[e] in the same way as he refers to it as "a more spiritual gospel".[4] "To Clement, both versions were the Gospel of Mark".[102] The purpose of the gospel was supposedly to encourage knowledge (gnosis) among more advanced Christians, and it is said to have been in use in liturgies in Alexandria.[25]

The quotes from Secret Mark

[edit]The letter includes two excerpts from the Secret Gospel. The first passage, Clement says, was inserted between Mark 10:34 and 35; after the paragraph where Jesus on his journey to Jerusalem with the disciples makes the third prediction of his death, and before Mark 10:35–45 where the disciples James and John ask Jesus to grant them honor and glory.[103] It shows many similarities with the story in John 11:1–44 where Jesus raises Lazarus from the dead.[23][24] According to Clement, the passage reads word for word (Biblical Greek: κατὰ λέξιν, romanized: kata lexin):[104]

And they come into Bethany. And a certain woman whose brother had died was there. And, coming, she prostrated herself before Jesus and says to him, "Son of David, have mercy on me." But the disciples rebuked her. And Jesus, being angered, went off with her into the garden where the tomb was, and straightway a great cry was heard from the tomb. And going near Jesus rolled away the stone from the door of the tomb. And straightway, going in where the youth was, he stretched forth his hand and raised him, seizing his hand. But the youth, looking upon him, loved him and began to beseech him that he might be with him. And going out of the tomb they came into the house of the youth, for he was rich. And after six days Jesus told him what to do and in the evening the youth comes to him, wearing a linen cloth over his naked body. And he remained with him that night, for Jesus taught him the mystery of the kingdom of God. And thence, arising, he returned to the other side of the Jordan.[19]

The second excerpt is very brief and was inserted in Mark 10:46. Clement says that "after the words, 'And he comes into Jericho' [and before 'and as he went out of Jericho'] the secret Gospel adds only":[19]

And the sister of the youth whom Jesus loved and his mother and Salome were there, and Jesus did not receive them.[19]

Clement continues: "But the many other things about which you wrote both seem to be and are falsifications."[19] Just as Clement is about to give the true explanation of the passages, the letter breaks off.

These two excerpts comprise the entirety of the Secret Gospel material. No separate text of the secret gospel is known to survive, and it is not referred to in any other ancient source.[105][106][107] Some scholars have found it suspicious that an authentic ancient Christian text would be preserved only in a single, late manuscript.[31][108] However, this is not unprecedented.[109][f]

Debate on authenticity and authorship

[edit]1970s and 1980s

[edit]Reception and Smith's analysis

[edit]

Among scholars, there is no consensus opinion on the authenticity of the letter,[110][30][31] not least because the manuscript's ink has never been tested.[30][111] At the beginning, the authenticity of the letter was not in doubt,[34] and early reviewers of Smith's books generally agreed that the letter was genuine.[112] However, soon suspicion arose and the letter achieved notoriety, mainly "because it was intertwined" with Smith's own interpretations.[12] Through detailed linguistic investigations, Smith argued that it could likely be a genuine letter of Clement. He indicated that the two quotations go back to an original Aramaic version of Mark, which served as a source for both the canonical Mark and the Gospel of John.[113][12][114][115] Smith argued that the Christian movement began as a mystery religion[67] with baptismal initiation rites,[g][96] and that the historical Jesus was a magus possessed by the Spirit.[116] Most disturbing to Smith's reviewers was his passing suggestion that the baptismal initiation rite administered by Jesus to his disciples may have gone as far as a physical union.[67][h][i]

Authenticity and authorship

[edit]In the first phase, the letter was thought to be genuine, while Secret Mark often was regarded as a typical apocryphal second-century gospel sprung from the canonical traditions.[34] This pastiche theory was promoted by F. F. Bruce (1974), who saw the story of the young man of Bethany clumsily based on the raising of Lazarus in the Gospel of John. Thus, he saw the Secret Mark narrative as derivative and denied that it could be either the source of the story of Lazarus or an independent parallel.[117] Raymond E. Brown (1974) came to the conclusion that the author of Secret Mark "may well have drawn upon" the Gospel of John, "at least from memory".[118] Patrick W. Skehan (1974) supported this view, calling the reliance on John "unmistakable".[119] Robert M. Grant (1974) thought that Smith definitely had proved that the letter was written by Clement,[120] but found in Secret Mark elements from each of the four canonical gospels,[j][121] and arrived at the conclusion that it was written after the first century.[122] Helmut Merkel (1974) also concluded that Secret Mark is dependent on the four canonical gospels after analyzing the key Greek phrases,[123] and that even if the letter is genuine it tells of nothing more than that an expanded version of Mark was in existence in Alexandria in AD 170.[116] Frans Neirynck (1979) argued that Secret Mark was virtually "composed with the assistance of a concordance" of the canonical gospels[124] and wholly dependent on them.[125][126] N. T. Wright wrote in 1996 that most scholars who accept the text as genuine see in the Secret Gospel of Mark "a considerably later adaptation of Mark in a decidedly gnostic direction."[127]

However, approximately the same number of scholars (at least 25 versus at least 32)[128][129] did not consider Secret Mark to be "a worthless patchwork fabrication" but saw instead a healing story quite like other miracle stories in the Synoptic Gospels; a story that progressed smoothly without any obvious rough connections and inconsistencies as is found in the corresponding story of the raising of Lazarus in the Gospel of John. Like Smith, they mostly thought that the story was based on oral tradition, although they generally rejected his idea of an Aramaic proto-gospel.[128]

Quentin Quesnell and Charles Murgia

[edit]

The first scholar to publicly question the letter's authenticity was Quentin Quesnell (1927–2012) in 1975.[130] Quesnell's principal argument was that the actual manuscript had to be examined before it could be deemed authentic,[131] and he suggested that it might be a modern hoax.[132][34] He said that the publication of Otto Stählin's concordance of Clement in 1936,[133] would make it possible to imitate Clement's style,[134][34] which means that if it is a forgery, it would necessarily have been forged after 1936.[135][136] On his last day of stay at the monastery, Smith found a catalogue from 1910 in which 191 books were listed,[137][138][139] but not the Vossius book. Quesnell and others have argued that this fact supports the supposition that the book never was part of the Mar Saba library,[140] but was brought there from outside, by for example Smith, with the text already inscribed.[141][142] However, this has been contested. Smith found almost 500 books at his stay,[k][144] so the list was far from complete[145] and the silence from incomplete catalogues cannot be used as arguments against the existence of a book at the time the catalogue was made, Smith argued.[137]

Although Quesnell did not accuse Smith of having forged the letter, his "hypothetical forger matched Smith's apparent ability, opportunity, and motivation," and readers of the article, as well as Smith himself, saw it as an accusation that Smith was the culprit.[82][34] Since at the time, no one but Smith had seen the manuscript, some scholars suggested that there might not even be a manuscript.[34][l]

Charles E. Murgia followed Quesnell's allegations of forgery with further arguments,[146] such as calling attention to the fact that the manuscript has no serious scribal errors, as one would expect of an ancient text copied many times,[147][116][148] and by suggesting that the text of Clement had been designed as a sphragis, a "seal of authenticity", to answer questions from the readers why Secret Mark was never heard of before.[149] Murgia found Clement's exhortation to Theodore, that he should not concede to the Carpocratians "that the secret Gospel is by Mark, but should even deny it on oath",[19] to be ludicrous, since there is no point in "urging someone to commit perjury to preserve the secrecy of something which you are in the process of disclosing".[150] Later Jonathan Klawans, who thinks the letter is suspect but possibly authentic, bolstered Murgia's argument by saying that if Clement had urged Theodore to lie to the Carpocratians, it would have been easier for him to follow "his own advice" and lie to Theodore instead.[151] Scott Brown, however, finds this argument to be flawed since there is no point in denying the existence of a gospel that the Carpocratians have in their possession. Brown advocates that Theodore instead is told to assure that the adulterated or forged Carpocratian gospel was not written by Mark, which, according to Brown, would be at least a half-truth and also something Clement could have said for the benefit of the church.[152]

Smith gave some thought to Murgia's arguments but later dismissed them as being based on a misreading,[34] and he thought Murgia "fell into a few factual errors".[153][154] Although forgers use the technique of "explaining the appearance and vouching for the authenticity", the same form is also often used to present material hitherto unheard of.[153] Even though none of Clement's other letters have survived,[108][155] there also seems to have been a collection of at least 21 of his letters at Mar Saba in the 8th century when John of Damascus, who worked there for more than 30 years (c. 716–749), quoted from that collection.[156][m] In the early 18th century, a great fire at Mar Saba also burned out a cave in which many of the oldest manuscripts were stored. Smith speculated that a letter of Clement could partly have survived the fire, and a monk could have copied it into the endpapers of the monastery's edition of the letters of Ignatius[b] in order to preserve it.[159][160] Smith argued that the simplest explanation would be that the text was "copied from a manuscript that had lain for a millennium or more in Mar Saba and had never been heard of because it had never been outside the monastery."[153][161]

Murgia anyway ruled out the possibility that Smith could have forged the letter as, according to him, Smith's knowledge of Greek was insufficient and nothing in his book indicated a fraud.[162] Murgia seemingly thought the letter was created in the 18th century.[163]

Morton Smith objected to insinuations that he would have forged the letter by, for example, calling Quesnell's 1975 article[164] an attack.[165][166] And when the Swedish historian Per Beskow in Strange Tales about Jesus from 1983,[167] the first English edition of his 1979 Swedish book,[168] wrote that there were reasons to be skeptical about the genuineness of the letter, Smith got upset and responded by threatening to sue the English language publisher, Fortress Press of Philadelphia, for $1 million dollars.[169][170] This caused Fortress to withdraw the book from circulation, and a new edition was released in 1985 in which passages that Smith had objected to were removed,[171] and with Beskow emphasizing that he did not accuse Smith of forging it.[170] Although Beskow had doubts about the letter's authenticity, he preferred "to regard this as an open question".[170]

Secret Markan priority

[edit]

Morton Smith summarized the situation in a 1982 article. He argued that "most scholars would attribute the letter to Clement" and that no strong argument against it had been presented.[172][33] The attribution of the gospel to Mark was though "universally rejected", with the most common opinion being that the gospel is "a pastiche composed from the canonical gospels" in the second century.[33][n]

After Smith's summary of the situation, other scholars did support Secret Markan priority. Ron Cameron (1982) and Helmut Koester (1990) argued that Secret Mark preceded canonical Mark, which in fact would be an abbreviation of Secret Mark.[o] With a few modifications, Hans-Martin Schenke supported Koester's theory,[177][36] and also John Dominic Crossan has presented a to some extent similar "working hypothesis" to that of Koester: "I consider that canonical Mark is a very deliberate revision of Secret Mark."[178][179] Marvin Meyer included Secret Mark in his reconstruction of the origin of the Gospel of Mark.[180][181]

1991 (Smith's death) to 2005

[edit]Intensified accusations against Smith

[edit]The allegations against Smith for having forged the Mar Saba manuscript became even more pronounced after his death in 1991.[182][183][94] Jacob Neusner, a specialist in ancient Judaism, was Morton Smith's student and admirer but later, in 1984, there was a public falling out between them after Smith publicly denounced his former student's academic competence.[184] Neusner subsequently described Secret Mark as "the forgery of the century".[185][186] Yet Neusner never wrote any detailed analysis of Secret Mark or an explanation of why he thought it was a forgery.[p]

The language and style of the Clement letter

[edit]Most scholars who have studied the letter and written about it assume the letter was written by Clement.[188][189] Most patristic scholars think the language is typical of Clement and that in manner and matter the letter seems to have been written by him.[27] In "the first epistolary analysis of Clement's letter to Theodore", Jeff Jay demonstrates that the letter "comports in form, content, and function with other ancient letters that addressed similar circumstances",[190] and "is plausible in light of letter writing in the late second or early third century".[191] He claims that it would require a forger with a breadth of knowledge that is "superhuman" to have forged the letter.[q] In the main, the Clementine scholars have accepted the authenticity of the letter, and in 1980 it was also included in the concordance of the acknowledged genuine writings of Clement,[133][28] although the inclusion is said by the editor Ursula Treu to be provisional.[193][194]

In 1995, Andrew H. Criddle made a statistical study of Clement's letter to Theodore with the help of Otto Stählin's concordance of the writings of Clement.[133][48] According to Criddle, the letter had too many hapax legomena, words used only once before by Clement, in comparison to words never before used by Clement, and Criddle argued that this indicates that a forger had "brought together more rare words and phrases" found in the authentic writings of Clement than Clement would have used.[195] The study has been criticized for, among other things, focusing on "Clement's least favourite words" and for the methodology itself, which turns out to be "unreliable in determining authorship".[196] When tested on Shakespeare's writings only three out of seven poems were correctly identified.[197][198][r]

The Mystery of Mar Saba

[edit]In 2001, Philip Jenkins drew attention to a novel by James H. Hunter entitled The Mystery of Mar Saba, which first appeared in 1940 and was popular at the time.[200][201] Jenkins saw unusual parallels to Clement's letter to Theodore and Smith's description of his discovery in 1958,[202] but did not explicitly state that the novel inspired Smith to forge the text.[203] Later Robert M. Price,[204] Francis Watson[205] and Craig A. Evans[206] developed the theory that Morton Smith would have been inspired by this novel to forge the letter. This assumption has been contested by, among others, Scott G. Brown, who writes that apart from "a scholar discovering a previously unknown ancient Christian manuscript at Mar Saba, there are few parallels"[207][s] – and in a rebuttal to Evans, he and Allan J. Pantuck find the alleged parallel between the Scotland Yard detective Lord Moreton's last name and Morton Smith's first name puzzling, since Morton Smith got his name long before the novel was written.[209] Francis Watson finds the parallels so convincing that "the question of dependence is unavoidable",[210] while Allan J. Pantuck thinks they are too generic or too artful to be persuasive.[211] Javier Martínez, who thinks the question of forgery is open to debate, regards the suggestion that Hunter's novel would have inspired Smith to forge the text to be outlandish.[212] He wonders why it took more than four decades after the story of Smith's discovery made the front page of the New York Times[t] before anyone realized that this so popular novel was Smith's source.[213] Martínez finds Watson's methods, by which he reaches the conclusion that "[t]here is no alternative but to conclude that Smith is dependent on" The Mystery of Mar Saba,[214] to be "surreal as a work of scholarship".[215] Timo Paananen asserts that neither Evans nor Watson clarifies what criteria they use to establish that these particular parallels are so "amazing, both in substance and in language",[216][217] and that they reduce the rigor of their criteria compared to how they dismiss "literary dependencies in other context".[218]

Chiasms in Mark

[edit]In 2003, John Dart proposed a complex theory of 'chiasms' (or 'chiasmus') running through the Gospel of Mark – a type of literary device he finds in the text.[219] Dart "[recovered] a formal structure to original Mark containing five major chiastic spans framed by a prologue and a conclusion."[220] According to Dart, his analysis supports the authenticity of Secret Mark.[220] His theory has been criticized, as it presupposes hypothetical changes in the text of Mark in order to work.[221]

Stalemate in the academy

[edit]

The fact that, for many years, no other scholars besides Smith were known to have seen the manuscript contributed to the suspicions of forgery.[226] This dissipated with the publication of color photographs in 2000,[86] and the revelation in 2003 that Guy Stroumsa and several others viewed the manuscript in 1976.[71][14] In response to the idea that Smith had kept other scholars from inspecting the manuscript, Scott G. Brown noted that he was in no position to do so.[14] The manuscript was still where Smith had left it when Stroumsa and company found it 18 years later,[71] and it did not disappear until many years after its relocation to Jerusalem and its separation from the book.[14] Charles Hedrick says that if anyone is to be blamed for the loss of the manuscript, it is the "[o]fficials of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate in Jerusalem", as it was lost while it was in their custody.[16]

In 2003 Charles Hedrick expressed frustration over the stalemate in the academy over the text's authenticity,[36] even though the Clementine scholars in the main had accepted the authenticity of the letter.[28] The same year, Bart Ehrman also stated that the situation still was the same as it was when Smith summarized it in 1982, namely that a majority of scholars considered the letter to be authentic, "and probably a somewhat smaller majority agreed that the quotations of Secret Mark actually derived from a version of Mark."[30][222]

The two camps could be illustrated, on the one hand by Larry Hurtado, who thinks it is "inadvisable to rest too much on Secret Mark" as the letter "that quotes it might be a forgery" and even if it is genuine, Secret Mark "may be at most an ancient but secondary edition of Mark produced in the second century by some group seeking to promote its own esoteric interests",[227] and by Francis Watson, who hopes and expects that Secret Mark will be increasingly ignored by scholars to avoid "that their work will be corrupted by association with it".[228] On the other hand, by Marvin Meyer, who assumes the letter to be authentic and in several articles, beginning in 1983,[229] used Secret Mark in his reconstructions, especially regarding the young man (neaniskos) "as a model of discipleship",[36][180] and by Eckhard Rau, who argues that as long as a physical examination of the manuscript is not possible and no new arguments against authenticity can be put forward, it is, although not without risk, judicious to interpret the text as originating from the circle of Clement of Alexandria.[230]

Other authors, like an Origenist monk in the early 5th century, have also been proposed for the letter.[231] Michael Zeddies suggested in 2017 that the letter was actually written by Origen of Alexandria (c. 184–c. 254).[232] The author of the letter is identified only in the title[233] and many ancient writings were misattributed.[234][235] According to Zeddies, the language of the letter, its concept and style, as well as its setting, "are at least as Origenian as they are Clementine".[236] Origen was also influenced by Clement and "shared his background in the Alexandrian church".[237] Furthermore, Origen actually had a pupil named Theodore.[238]

2005 to present

[edit]The debate intensified with the publication of three new books.[239] Scott G. Brown's revised doctoral dissertation Mark's Other Gospel from 2005,[240][72] was the first monograph that dealt only with Secret Mark since Smith's books in 1973.[63][66][77] Brown argued that both the letter and Secret Mark were authentic.[241] The same year Stephen C. Carlson published The Gospel Hoax[242] in which he spells out his case that Morton Smith, himself, was both the author and the scribe of the Mar Saba manuscript.[241] And in 2007, musicologist Peter Jeffery published The Secret Gospel of Mark Unveiled, in which he accuses Morton Smith of having forged the letter.[243]

Mark's Other Gospel

[edit]

In Mark's Other Gospel (2005),[240] Scott G. Brown challenged "all previous statements and arguments made against the letter's authenticity"[241] and he criticized those scholars saying that the letter was forged for not offering proof for their claims,[244] and for not making a distinction between the letter and Smith's own interpretation of it.[77] Brown claimed that Smith could not have forged the letter since he did not comprehend it "well enough to have composed it."[245] Brown also criticized the pastiche theory, according to which Secret Mark would be created from a patchwork of phrases from especially the Synoptic Gospels, for being speculative, uncontrollable and "unrealistically complicated".[246] Most parallels between Secret Mark and Matthew and Luke are, according to Brown, "vague, trivial, or formulaic".[247] The only close parallels are to canonical Mark, but a characteristic of Mark is "repetition of exact phrases",[248] and Brown finds nothing suspicious in the fact that a longer version of the Gospel of Mark contains "Markan phrases and story elements".[249] He also explored several Markan literary characteristics in Secret Mark, such as verbal echoes, intercalations and framing stories, and came to the conclusion that the author of the Secret Gospel of Mark "wrote so much like Mark that he could very well be Mark himself",[241] that is, whoever "wrote the canonical gospel."[250]

The Gospel Hoax

[edit]In The Gospel Hoax (2005),[242] Stephen C. Carlson argued that Clement's letter to Theodore is a forgery and only Morton Smith could have forged it, as he had the "means, motive, and opportunity" to do so.[251] Carlson claimed to have identified concealed jokes left by Smith in the letter which according to him showed that Smith created the letter as a hoax.[251] He especially identified two: the first, a reference to salt that "loses its savor", according to Carlson by being mixed with an adulterant, and that presupposes free-flowing salt which in turn is produced with the help of an anti-caking agent, "a modern invention" by an employee of the Morton Salt Company – a clue left by Morton Smith pointing to himself;[252][77] and the second, that Smith would have identified the handwriting of the Clement letter as done by himself in the 20th century "by forging the same eighteenth-century handwriting in another book and falsely attributing that writing to a pseudonymous twentieth-century individual named M. Madiotes [Μ. Μαδιότης], whose name is a cipher pointing to Smith himself."[253] The 'M' would stand for Morton, and 'Madiotes' would be derived from the Greek verb μαδώ, madō meaning both 'to lose hair' and figuratively 'to swindle' – with the bald swindler being the balding Morton Smith.[254][255] When Carlson examined the printed reproductions of the letter found in Smith's scholarly book,[63] he said he noted a "forger's tremor."[256] Thus, according to Carlson the letters had not actually been written at all, but drawn with shaky pen lines and with lifts of the pen in the middle of strokes.[257] Many scholars became convinced by Carlson's book that the letter was a modern forgery and some who previously defended Smith changed their position.[u] Craig A. Evans, for instance, came to think that "the Clementine letter and the quotations of Secret Mark embedded within it constitute a modern hoax, and Morton Smith almost certainly is the hoaxer."[259][260][77]

However, these theories by Carlson have, in their own turn, been challenged by subsequent scholarly research, especially by Scott G. Brown in numerous articles.[261][262][263][264][265] Brown writes that Carlson's Morton Salt Company clue "is one long sequence of mistakes" and that "the letter nowhere refers to salt being mixed with anything" – only "the true things" are mixed.[266] He also says that salt can be mixed without being free-flowing with the help of mortar and pestle,[267] an objection that gets support from Kyle Smith, who shows that according to ancient sources salt both could be and was "mixed and adulterated".[268][269] Having gained access to the original uncropped photograph, Allan Pantuck and Scott Brown also demonstrated that the script Carlson thought was written by M. Madiotes actually was written by someone else and was an 18th-century hand unrelated to Clement's letter to Theodore; that Smith did not attribute that handwriting to a contemporary named M. Madiotes (M. Μαδιότης), and that he afterwards corrected the name Madiotes to Madeotas (Μαδεότας) which may, in fact, be Modestos (Μοδέστος), a common name at Mar Saba.[270][271]

In particular, on the subject of the handwriting, Roger Viklund in collaboration with Timo S. Paananen has demonstrated that "all the signs of forgery Carlson unearthed in his analysis of the handwriting", such as a "forger's tremor",[272] are only visible in the images Carlson used for his handwriting analysis. Carlson chose "to use the halftone reproductions found in [Smith's book] Clement of Alexandria and a Secret Gospel of Mark" where the images were printed with a line screen made of dots. If the "images are magnified to the degree necessary for forensic document examination" the dot matrix will be visible and the letters "will not appear smooth".[273] Once the printed images Carlson used were replaced with the original photographs, the signs of tremors also disappeared.[272]

On the first York Christian Apocrypha Symposium on the Secret Gospel of Mark held in Canada in 2011, very little of Carlson's evidence was discussed.[v][274] Even Pierluigi Piovanelli – who thinks Smith committed a sophisticated forgery[275] – writes that the fact that "the majority of Carlson's claims" have been convincingly dismissed by Brown and Pantuck[276] and that no "clearly identifiable 'joke'" is embedded within the letter, "tend to militate against Carlson's overly simplistic hypothesis of a hoax."[277]

The Secret Gospel of Mark Unveiled

[edit]In The Secret Gospel of Mark Unveiled (2007),[278] Peter Jeffery argued that "the letter reflected practices and theories of the twentieth century, not the second",[243] and that Smith wrote Clement's letter to Theodore with the purpose of creating "the impression that Jesus practiced homosexuality".[279] Jeffery reads the Secret Mark story as an extended double entendre that tells "a tale of 'sexual preference' that could only have been told by a twentieth-century Western author"[280] who inhabited "a homoerotic subculture in English universities".[281][282] Jeffery's thesis has been contested by, for example, Scott G. Brown[283] and William V. Harris. Jeffery's two main arguments, those concerning liturgy and homoeroticism, are according to Harris unproductive and he writes that Jeffery "confuses the question of the authenticity of the text and the validity of Smith's interpretations" by attacking Smith and his interpretation and not Secret Mark.[284] The homoerotic argument, according to which Smith would have written the document to portray Jesus as practicing homosexuality, does not work either. In his two books on Secret Mark, Smith "gives barely six lines to the subject".[284] Jeffery's conclusion that the document is a forgery "because no young Judaean man" would approach "an older man for sex" is according to Harris also invalid, since there is "no such statement" in Secret Mark.[284]

Smith's correspondence

[edit]

In 2008, extensive correspondence between Smith and his teacher and lifelong friend Gershom Scholem was published, where they for decades discuss Clement's letter to Theodore and Secret Mark.[285] The book's editor, Guy Stroumsa, argues that the "correspondence should provide sufficient evidence of his [i.e., Smith's] intellectual honesty to anyone armed with common sense and lacking malice."[44] He thinks it shows "Smith's honesty",[286] and that Smith could not have forged the Clement letter, for, in the words of Anthony Grafton, the "letters show him discussing the material with Scholem, over time, in ways that clearly reflect a process of discovery and reflection."[287][288] Pierluigi Piovanelli has however contested Stroumsa's interpretation. He believes that the correspondence shows that Smith created an "extremely sophisticated forgery" to promote ideas he already held about Jesus as a magician.[275] Jonathan Klawans does not find the letters to be sufficiently revealing, and on methodological grounds, he thinks that letters written by Smith cannot give a definite answer to the question of authenticity.[289]

Smith's beforehand knowledge

[edit]A number of scholars have argued that the salient elements of Secret Mark were themes of interest to Smith which he had studied before the discovery of the letter in 1958.[w][293] In other words, Smith would have forged a letter that supported ideas he already embraced.[294] Pierluigi Piovanelli is suspicious about the letter's authenticity as he thinks it is "the wrong document, at the wrong place, discovered by the wrong person, who was, moreover, in need of exactly that kind of new evidence to promote new, unconventional ideas".[295] Craig Evans argues that Smith before the discovery had published three studies, in 1951,[296] 1955[297] and 1958,[298] in which he discussed and linked "(1) "the mystery of the kingdom of God" in Mark 4:11, (2) secrecy and initiation, (3) forbidden sexual, including homosexual, relationships and (4) Clement of Alexandria".[299]

This hypothesis has been contested mainly by Brown and Pantuck. First, they reject the idea that something sexual is even said to take place between Jesus and the young man in Secret Mark,[300][301] and if that is the case, then there are no forbidden sexual relations in the Secret Mark story. Second, they challenge the idea that Smith made the links Evans and others claim he did. They argue that Smith, in his doctoral dissertation from 1951,[296] did not link more than two of the elements – the mystery of the kingdom of God to secret teachings. Forbidden sexual relations, such as "incest, intercourse during menstruation, adultery, homosexuality, and bestiality", is just one subject among several others in the scriptures that the Tannaim deemed should be discussed in secret.[302][303] Further, they claim that Smith in his 1955 article[297] also only linked the mystery of the kingdom of God to secret teachings.[304] In the third example, an article Smith wrote in 1958,[298] he only "mentioned Clement and his Stromateis as examples of secret teaching".[305][306] Brown and Pantuck consider it to be common knowledge among scholars of Christianity and Judaism that Clement and Mark 4:11 deal with secret teaching.[305]

Handwriting experts and Smith's ability

[edit]

The November/December 2009 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review (BAR 35:06) features a selection of articles dedicated to the Secret Gospel of Mark. Charles W. Hedrick wrote an introduction to the subject,[51] and both Hershel Shanks[307] and Helmut Koester[308] wrote articles in support of the letter's authenticity. Since the three pro-forgery scholars who were contacted declined to participate,[x] Shanks had to make the argument for forgery himself.[309] Helmut Koester writes that Morton Smith "was not a good form-critical scholar" and that it "would have been completely beyond his ability to forge a text that, in terms of form-criticism, is a perfect older form of the same story as appears in John 11 as the raising of Lazarus."[310] In 1963 Koester and Smith met several hours a day for a week to discuss Secret Mark. Koester then realized that Smith really struggled to understand the text and to decipher the handwriting. Koester writes: "Obviously, a forger would not have had the problems that Morton was struggling with. Or Morton Smith was an accomplished actor and I a complete fool."[310]

In late 2009, Biblical Archaeology Review commissioned two Greek handwriting experts to evaluate "whether the handwriting of the Clement letter is in an authentic 18th-century Greek script" and whether Morton Smith could have written it.[y] They had at their disposal high-resolution scans of the photographs of the Clement letter and known samples of Morton Smith's English and Greek handwriting from 1951 to 1984.[311]

Venetia Anastasopoulou, a questioned document examiner and expert witness with experience in many Greek court cases,[z] noticed three very different writings. Clement's letter, in her opinion, was written skillfully with "freedom, spontaneity and artistic flair" by a trained scribe who could effectively express his thoughts.[312] Likewise, Smith's English writing was "spontaneous and unconstrained, with a very good rhythm."[313] Smith's Greek writing, though, was "like that of a school student" who is unfamiliarized in Greek writing and unable "to use it freely" with ease.[314] Anastasopoulou concluded that in her professional opinion, Morton Smith, with high probability, could not have produced the handwriting of the Clement letter.[315] She further explained, contrary to Carlson's assertion, that the letter did not have any of the typical signs of forgery, such as "lack of natural variations" appearing to be drawn or having "poor line quality", and that when a large document, such as this letter by Clement, is consistent throughout, "we have a first indication of genuineness".[aa]

However, Agamemnon Tselikas, a distinguished Greek paleographer[ab] and thus a specialist in deciding when a particular text was written and in what school this way of writing was taught, thought the letter was a forgery. He noticed some letters with "completely foreign or strange and irregular forms". Contrary to Anastasopoulou's judgment, he thought some lines were non-continuous and that the hand of the scribe was not moving spontaneously.[ac] He stated that the handwriting of the letter is an imitation of 18th-century Greek script and that the most likely forger was either Smith or someone in Smith's employ.[2] Tselikas suggests that Smith, as a model for the handwriting, could have used four 18th-century manuscripts from the Thematon monastery he visited in 1951.[ad][316] Allan Pantuck could, though, demonstrate that Smith never took any photographs of these manuscripts and could consequently not have used them as models.[317][318] Since, according to Anastasopoulou's conclusion, the letter is written by a trained scribe with a skill that surpasses Smith's ability, in the words of Michael Kok, "the conspiracy theory must grow to include an accomplice with training in eighteenth-century Greek paleography".[319]

Having surveyed the archives of Smith's papers and correspondence, Pantuck comes to the conclusion that Smith was not capable of forging the letter; that his Greek was not good enough to compose a letter in Clement's thought and style and that he lacked the skills needed to imitate a difficult Greek 18th-century handwriting.[320] Roy Kotansky, who worked with Smith on translating Greek, says that although Smith's Greek was very good, it "was not that of a true papyrologist (or philologist)". According to Kotansky, Smith "certainly could not have produced either the Greek cursive script of the Mar Saba manuscript, nor its grammatical text" and writes that few are "up to this sort of task";[321] which, if the letter is forged, would be "one of the greatest works of scholarship of the twentieth century", according to Bart Ehrman.[ae]

Scott G. Brown and Eckhard Rau argue that Smith's interpretation of the longer passage from Secret Mark cannot be reconciled with its content,[322][323] and Rau thinks that if Smith really forged the letter, he should have been able to make it more suitable for his own theories.[322] Michael Kok thinks that the "Achilles' heel of the forgery hypothesis" is that Smith seemingly did not have the necessary skills to forge the letter.[324]

The Secret Gospel of Mark

[edit]In The Secret Gospel of Mark,[325] historians Geoffrey Smith and Brent Landau propose an interpretation that goes against both major camps in the dispute. They do not believe that the Mar Saba letter was forged by Smith; based on existing handwriting analysis plus further analysis from experts they sought out themselves, they assert that the version of the letter found by Smith was most likely transcribed during the 18th or early 19th centuries, and agree with those who feel Smith did not have the skills necessary to either compose the letter's contents or simulate handwriting from those dates.

However, they also, based on internal evidence, reject the possibility that the document was genuinely written by Clement of Alexandria. The most important piece of evidence is that the letter writer takes for granted that Mark the Evangelist was the first bishop of Alexandria. Before the publication of the Mar Saba letter, the oldest evidence for this belief in Christian circles came from the 4th century Ecclesiastical History written by Eusebius; beyond the contents of Secret Mark itself, one of the features of the Mar Saba letter of most interest to historians is that it would be very early evidence of belief that Mark had been bishop of Alexandria. However, Smith and Landau point out that Clement never identifies Mark as one of his predecessors in the see in any of his confirmed writings, even ones in which he discusses Mark the Evangelist's career, and so they reject the idea that Clement held this belief. Other material in the letter is similarly anachronistic, and appears to have been written by someone working from Eusebius, who wrote nearly a century after Clement's death. In particular, they believe the material in the letter about the Carpocratians is much more similar to Eusebius's account of the group than it is to writings about them in Clement's confirmed works.

Smith and Landau believe the letter to be a pseudepigraphal composition from late antiquity. They note that Morton Smith shared the letter with his mentor Arthur Nock before publication, and Nock came to that conclusion upon reading it. Geoffrey Smith and Landau believe the letter was composed in the context of a late antique controversy raging in Palestinian monasteries like Mar Saba over adelphopoiesis, or "brother-making," a ceremony which recognized an intense emotional and spiritual relationship (not necessarily erotic, though sometimes viewed as such by contemporaries and modern observers) between two monks. The authors believe the letter is an attempt to defend the practice by connecting it to Jesus's ministry, drawing from canonical biblical episodes such as Jesus's resurrection of Lazarus and the mysterious naked fugitive fleeing the scene of Jesus's arrest.

Interpretation

[edit]Smith's theories about the historical Jesus

[edit]Smith thought that the scene in which Jesus taught the young man "the mystery of the kingdom of God" at night, depicted an initiation rite of baptism[g] which Jesus offered his closest disciples.[326][327] In this baptismal rite "the initiate united with Jesus' spirit" in a hallucinatory experience, and then they "ascended mystically to the heavens." The disciple would be set free from the Mosaic Law and they would both become libertines.[328] The libertinism of Jesus was then later suppressed by James, the brother of Jesus, and Paul.[116][329] The idea that "Jesus was a libertine who performed a hypnotic rite of" illusory ascent to the heavens,[330][331] not only seemed far-fetched but also upset many scholars,[330][332] who could not envision that Jesus would be portrayed in such a way in a trustworthy ancient text.[333] Scott Brown argues though that Smith's usage of the term libertine did not mean sexual libertinism, but freethinking in matters of religion, and that it refers to Jews and Christians who chose not to keep the Mosaic Law.[328] In each of his books on Secret Mark, Smith made one passing suggestion that Jesus and the disciples might have united also physically in this rite,[334][335] but he thought that the essential thing was that the disciples were possessed by Jesus' spirit".[h] Smith acknowledged that there is no way to know if this libertinism can be traced as far back as Jesus.[336][i]

In his later work, Morton Smith increasingly came to see the historical Jesus as practicing some type of magical rituals and hypnotism,[26][68] thus explaining various healings of demoniacs in the gospels.[338] Smith carefully explored for any traces of a "libertine tradition" in early Christianity and in the New Testament.[339][340] Yet there is very little in the Mar Saba manuscript to give backing to any of this. This is illustrated by the fact that in his later book, Jesus the Magician, Smith devoted only 12 lines to the Mar Saba manuscript,[341] and never suggested "that Jesus engaged in sexual libertinism".[342]

Lacunae and continuity

[edit]The two excerpts from Secret Mark suggest resolutions to some puzzling passages in the canonical Mark.

The young man in the linen cloth

[edit]

In Mark 14:51–52, a young man (Greek: νεανίσκος, neaniskos) in a linen cloth (Greek: σινδόνα, sindona) is seized during Jesus' arrest, but he escapes at the cost of his clothing.[343] This passage seems to have little to do with the rest of the narrative, and it has given cause to various interpretations. Sometimes it is suggested that the young man is Mark himself.[344][345][af] However, the same Greek words (neaniskos and sindona) are also used in Secret Mark. Several scholars, such as Robert Grant and Robert Gundry, suggest that Secret Mark was created based on Mark 14:51, 16:5 and other passages and that this would explain the similarities.[j] Other scholars, such as Helmut Koester[175] and J. D. Crossan,[350] argue that the canonical Mark is a revision of Secret Mark. Koester thinks that an original Proto-Mark was expanded with, among other things, the raising of the youth in Secret Mark and the fleeing naked youth during Jesus' arrest in Mark 14:51–52, and that this gospel version later was abridged to form the canonical Mark.[36] According to Crossan, Secret Mark was the original gospel. In the creation of canonical Mark, the two Secret Mark passages quoted by Clement were removed and then dismembered and scattered throughout canonical Mark to form the neaniskos-passages.[351] Miles Fowler and others argue that Secret Mark originally told a coherent story, including that of a young man. From this gospel, some passages were removed (by the original author or by someone else) to form canonical Mark. In this process, some remnants were left, such as that of the fleeing naked young man, while other passages may have been completely lost.[38][177][352]

Marvin Meyer sees the young man in Secret Mark as a paradigmatic disciple that "functions as a literary rather than a historical figure."[353] The young man (neaniskos) wears only "a linen cloth" (sindona) "over his naked body".[19] This is reminiscent of Mark 14:51–52, where, in the garden of Gethsemane, an unnamed young man (neaniskos) who is wearing nothing but a linen cloth (sindona) about his body is said to follow Jesus, and as they seize him, he runs away naked, leaving his linen cloth behind.[354] The word sindōn is also found in Mark 15:46 where it refers to Jesus' burial wrapping.[355][356] And in Mark 16:5 a neaniskos (young man) in a white robe, who in Mark does not seem to function as an angel,[ag] is sitting in the empty tomb when the women arrive to anoint Jesus' body.[38][357]

Miles Fowler suggests that the naked fleeing youth in Mark 14:51–52, the youth in the tomb of Jesus in Mark 16:5 and the youth Jesus raises from the dead in Secret Mark are the same youth; but that he also appears as the rich (and in the parallel account in Matthew 19:20, "young") man in Mark 10:17–22, whom Jesus loves and urges to give all his possessions to the poor and join him.[38] This young man is furthermore by some scholars identified as both Lazarus (due to the similarities between Secret Mark 1 and John 11) and the beloved disciple (due to the fact that Jesus in Secret Mark 2 is said to have loved the youth, and that in the gospels he is said to have loved only the three siblings Martha, Mary and Lazarus (John 11:5), the rich man (Mark 10:22) and the beloved disciple).[ah][359] Hans-Martin Schenke interprets the scene of the fleeing youth in Gethsemane (Mark 14:51–52) as a symbolic story in which the youth is not human but rather a shadow, a symbol, an ideal disciple. He sees the reappearing youth as a spiritual double of Jesus and the stripping of the body as a symbol of the soul being naked.[360]

Marvin Meyer finds a subplot, or scenes or vignettes, "in Secret Mark that is present in only a truncated form in canonical Mark", about a young man as a symbol of discipleship who follows Jesus throughout the gospel story.[23][361] The first trace of this young man is found in the story of the rich man in Mark 10:17–22 whom Jesus loves and "who is a candidate for discipleship"; the second is the story of the young man in the first Secret Mark passage (after Mark 10:34) whom Jesus raises from the dead and teaches the mystery of the kingdom of God and who loves Jesus; the third is found in the second Secret Mark passage (at Mark 10:46) in which Jesus rejects Salome and the sister of the youth whom Jesus loved and his mother; the fourth is in the story of the escaping naked young man in Gethsemane (Mark 14:51–52); and the fifth is found in the story of the young man in a white robe inside the empty tomb, a youth who informs Salome and the other women that Jesus has risen (Mark 16:1–8).[362] In this scenario, a once-coherent story in Secret Mark would, after much of the elements had been removed, form an incoherent story in canonical Mark with only embedded echoes of the story present.[38]

Lacuna in the trip to Jericho

[edit]The second excerpt from Secret Mark fills in an apparent lacuna in Mark 10:46: "They came to Jericho. As he and his disciples and a large crowd were leaving Jericho, Bartimaeus son of Timaeus, a blind beggar, was sitting by the roadside."[363][364] Morton Smith notes that "one of Mark's favorite formulas" is to say that Jesus comes to a certain place, but "in all of these except Mark 3:20 and 10:46 it is followed by an account of some event which occurred in the place entered" before he leaves the place.[365] Due to this apparent gap in the story, there has been speculation that the information about what happened in Jericho has been omitted.[363][366] According to Robert Gundry, the fact that Jesus cures the blind Bartimaeus on the way from Jericho justifies that Mark said that Jesus came to Jericho without saying that he did anything there. As a parallel, Gundry refers to Mark 7:31 where Jesus "returned from the region of Tyre, and went by way of Sidon towards the Sea of Galilee".[367] However, here Jesus is never said to have entered Sidon, and it is possible that this is an amalgamation of several introductory notices.[368]

With the addition from Secret Mark, the gap in the story would be solved: "They came to Jericho, and the sister of the youth whom Jesus loved and his mother and Salome were there, and Jesus did not receive them. As he and his disciples and a large crowd were leaving Jericho ..."[369] The fact that the text becomes more comprehensible with the addition from Secret Mark,[39] plus the fact that Salome is mentioned (and since she was "popular in heretical circles", the sentence could have been abbreviated for that reason), indicates that Secret Mark has preserved a reading that was deleted in the canonical Gospel of Mark.[370] Crossan thinks this shows that "Mark 10:46 is a condensed and dependent version of" the Secret Mark sentence.[371] Others argue that it would be expected that someone later would want to fill in the obvious gaps that occur in the Gospel of Mark.[372]

Relation to the Gospel of John

[edit]

The raising of Lazarus in John and the young man in Secret Mark

[edit]The resurrection of the young man by Jesus in Secret Mark bears such clear similarities to the raising of Lazarus in the Gospel of John (11:1–44) that it can be seen as another version of that story.[373] But although there are striking parallels between these two stories,[38] there are also "numerous, often pointless, contradictions."[374] If the two verses in Mark preceding Secret Mark are included, both stories tell us that the disciples are apprehensive as they fear Jesus' arrest. In each story it is the sister whose brother just died who approaches Jesus on the road and asks his help; she shows Jesus the tomb, which is in Bethany; the stone is removed, and Jesus raises the dead man who then comes out of the tomb.[375] In each story, the emphasis is upon the love between Jesus and this man,[24] and eventually, Jesus follows him to his home.[38] Each story occurs "at the same period in Jesus' career", as he has left Galilee and gone into Judea and then to Transjordan.[376][377]

Jesus' route in Mark

[edit]With the quoted Secret Mark passages added to the Gospel of Mark, a story emerges in which Jesus on his way to Jerusalem leaves Galilee and walks into northern Judea, then crosses the Jordan River east into Peraea and walks south through Peraea on the eastern side of the Jordan, meets the rich man whom he urges to give all his possessions to the poor and follow him (Mark 10:17–22), comes to Bethany, still on the other side of Jordan, and raises the young man from the dead (Secret Mark 1). He then crosses the river Jordan again and continues west while rejecting James' and John's request (Mark 10:35–45). He arrives at Jericho where he does not receive the three women (Mark 10:46 + Secret Mark 2) and then leaves Jericho to meet the blind Bartimaeus and give him back his sight.[378][379]

Two Bethanys

[edit]In each story, the raising of the dead man takes place in Bethany.[380] In the Gospel of John (10:40) Jesus is at "the place where John had been baptizing", which in John 1:28 is said to be a place named "Bethany beyond the Jordan" when Mary arrives and tells him that Lazarus is sick (John 11:1–3). Jesus follows her to another village called Bethany just outside of Jerusalem (John 11:17–18). In Secret Mark, the woman meets him at the same place, but he never travels to Bethany near Jerusalem. Instead, he just follows her to the young man since he already is in Bethany (beyond the Jordan).[381] In Secret Mark, the young man (Lazarus?) and his sister (Mary?) are not named, and their sister Martha does not even appear.[373][382]

Relations between the gospels

[edit]A number of scholars argue that the story in Secret Mark is based on the Gospel of John.[ai] Other scholars argue that the authors of Secret Mark and the Gospel of John independently used a common source or built on a common tradition.[24] The fact that Secret Mark refers to another Bethany than the one in the Gospel of John as the place for the miracle and omits the names of the protagonists, and since there are no traces in Secret Mark of the rather extensive Johannine redaction,[24] or of other Johannine characteristics, including its language, militate against Secret Mark being based on the Gospel of John.[374][386][387][388] Michael Kok thinks that this also militates against the thesis that the Gospel of John depends on Secret Mark and that it indicates that they both are based either on "oral variants of the same underlying tradition",[389] or on older written collections of miracle stories.[24] Koester thinks Secret Mark represents an earlier stage of development of the story.[24] Morton Smith tried to demonstrate that the resurrection story in Secret Mark does not contain any of the secondary traits found in the parallel story in John 11 and that the story in John 11 is more theologically developed. He concluded that the Secret Mark version of the story contains an older, independent, and more reliable witness to the oral tradition.[115][390][388]

Baptismal significance

[edit]Morton Smith saw the longer Secret Mark passage as a story of baptism.[g][393] According to Smith "the mystery of the kingdom of God" that Jesus taught the young man, was, in fact, a magical rite that "involved a purificatory baptism".[394][327] That this story depicts a baptism was in turn accepted by most scholars, also those otherwise critical to Smith's reconstructions.[393][395][396] And with the idea of the linen sheet as a baptismal garment followed the idea of nakedness and sex.[397]

But there has been some debate about this matter. For example, Scott G. Brown (while defending the authenticity of Secret Mark) disagrees with Smith that the scene is a reference to baptism. He thinks this is to profoundly misinterpret the text,[395] and he argues that if the story really had been about baptism, it would not have mentioned only teaching, but also water or disrobing and immersion.[393][398] He adds that "the young man's linen sheet has baptismal connotations, but the text discourages every attempt to perceive Jesus literally baptizing him."[399] Stephen Carlson agrees that Brown's reading is more plausible than Smith's.[400] The idea that Jesus practiced baptism is absent from the Synoptic Gospels, though it is introduced in the Gospel of John.[aj][367]

Brown argues that Clement, with the expression "the mystery of the kingdom of God,"[19] primarily meant "advanced theological instruction."[ak] On the other three occasions when Clement refers to "initiation in the great mysteries",[al] he always refers to the "highest stage of Christian theological education, two stages beyond baptism" – a philosophical, intellectual and spiritual experience "beyond the material realm".[403] Brown thinks the story of the young man is best understood symbolically, and the young man is best seen as an abstract symbol of "discipleship as a process of following Jesus in the way to life through death".[404] These matters also have a bearing on the debates about the authenticity of Secret Mark, because Brown implies that Smith, himself, did not quite understand his own discovery and it would be illogical to forge a text that you do not understand, to prove a theory it does not support.[am]

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Agamemnon Tselikas, "Grammatical and Syntactic Comments"[2]

- ^ a b c Isaac Vossius' first edition of the letters of Ignatius of Antioch was published in Amsterdam in 1646.[6] The book was catalogued by Morton Smith as MS 65.[7]

- ^ Smith, Morton, Manuscript Material from the Monastery of Mar Saba: Discovered, Transcribed, and Translated by Morton Smith, New York, privately published (Dec. 1958), pp. i, 10. It "was submitted to the U.S. Copyright Office on December 22, 1958."[54]

- ^ The meeting took place on December 29, 1960, in "the Horace Mann Auditorium, Teacher's College" at Columbia University.[62]

- ^ The Greek adjective mystikon (μυστικόν) has two basic meanings, "secret" and "mystic". Morton Smith chose to translate it to "secret",[101] which gives the impression that the gospel was concealed. Scott Brown translates it to "mystic", i.e. a gospel that has concealed meanings.[4]

- ^ For instance, were many apocryphal texts first encountered in and published from a single late manuscript, like the Infancy Gospel of Thomas and the Infancy Gospel of James.[31] In 1934 the previously unknown Egerton Gospel was purchased from an antique dealer in Egypt.[109]

- ^ a b c Smith got the idea that the gospel story depicts a rite of baptism from Cyril Richardson in January 1961.[391][392]

- ^ a b "'the mystery of the kingdom of God' ... was a baptism administered by Jesus to chosen disciples, singly, and by night. In this baptism the disciple was united with Jesus. The union may have been physical (... there is no telling how far symbolism went in Jesus' rite), but the essential thing was that the disciple was possessed by Jesus' spirit."[327]

- ^ a b "the disciple was possessed by Jesus' spirit and so united with Jesus. One with him, he participated by hallucination in Jesus' ascent into the heavens ... Freedom from the law may have resulted in completion of the spiritual union by physical union ... how early it began there is no telling."[337]

- ^ a b Robert Grant thinks the author took everything about the young man (Greek: neaniskos) from the canonical gospels (Mark 14:51–52, 16:5; Matt 19:20 & 22, Luke 7:14);[347] so also Robert Gundry (Mark 10:17–22, Matt 19:16–22, Luke 18:18–23).[348][349]

- ^ Smith wrote that the tower library alone (there were two libraries) must have had at least twice the number of books as were listed in the 1910 catalogue,[137] and he estimated them to between 400 and 500.[138] Smith's preserved notes on the Mar Saba books end with item 489.[143]

- ^ Eyer refers to Fitzmyer, Joseph A. "How to Exploit a Secret Gospel." America 128 (23 June 1973), pp. 570–572 and Gibbs, John G., review of Secret Gospel, Theology Today 30 (1974), pp. 423–426.[68]

- ^ In the Sacra Parallela, normally attributed to John of Damascus, a citation from Clement is introduced with: "From the twenty-first letter of Clement the Stromatist".[157] Opposite the view of later biographer, some modern scholars have argued that John of Damascus lived and worked mainly in Jerusalem until 742.[158]

- ^ Smith counted 25 scholars who thought Clement wrote the letter, 6 who did not offer an opinion and 4 who disagreed. 15 scholars thought the secret material was made up from the canonical gospels and 11 thought the material had existed before the Gospel of Mark was written.[173]

- ^ Secret Mark at "Early Christian Writings",[174] including citations from Helmut Koester,[175] and Ron Cameron.[176]

- ^ "The premise sustaining the most recent comments by [Donald] Akenson and [Jacob] Neusner is that the Letter to Theodore is an obvious forgery. If that were the case, they should have no problem providing definitive proof, but both avoided that responsibility by describing the document as so obviously fraudulent that proof would be superfluous."[187]

- ^ "But those who argue the letter is a twentieth century forgery must now allow that the forger had a solid knowledge of epistolography, ancient practices of composition and transmission, and the ability to weave a letter with fine generic texture, in addition to previously recognized competency in patristics, eighteenth-century Greek paleography, Markan literary techniques, and tremendous insight into the psychology and art of deception."[192]

- ^ Scott G. Brown refers to Ronald Thisted and Bradley Efron, who claim that "there is no consistent trend toward an excess or deficiency of new words".[199][197]

- ^ "I know that facts rarely get in the way of an incredible theory, but I would have thought that anyone who can imagine Smith producing the perfect forgery would at least have difficulty picturing him reading an anti-intellectual evangelical Christian spy novel.[208]

- ^ Sanka Knox, "A New Gospel Ascribed to Mark; Copy of Greek Letter Says Saint Kept 'Mysteries' Out A SECRET GOSPEL ASCRIBED TO MARK". New York Times, December 30, 1960.

- ^ Birger A. Pearson was persuaded by Carlson that Smith forged the text.[258]

- ^ Tony Burke: Apocryphicity – "Ancient Gospel or Modern Forgery? The Secret Gospel of Mark in Debate". The York University Christian Apocrypha Symposium Series 2011, April 29, 2011, York University (Vanier College). Reflections on the Secret Mark Symposium, part 2

- ^ Primarily Quentin Quesnell,[290] Stephen C. Carlson,[291] Francis Watson[292] and Craig A. Evans.[206]

- ^ The three pro-forgery scholars were Stephen C. Carlson, Birger A. Pearson and Bart D Ehrman.[309]

- ^ Biblical Archaeology Review, "Did Morton Smith Forge 'Secret Mark'?"

- ^ "Handwriting Expert Weighs In on the Authenticity of 'Secret Mark'" available online Archived 2010-07-05 at the Wayback Machine (access date April 15, 2018).

- ^ Venetia Anastasopoulou: "Can a Document in Itself Reveal a Forgery?" available online (access date May 1, 2018).

- ^ "Dr. Tselikas is director of the Center for History and Paleography of the National Bank of Greece Cultural Foundation and also of the Mediterranean Research Institute for Paleography, Bibliography and History of Texts."[2]

- ^ Agamemnon Tselikas, "Palaeographic Observations 1"[2]

- ^ Agamemnon Tselikas, "Textological Observations"[2]

- ^ "It is true that a modern forgery would be an amazing feat. For this to be forged, someone would have had to imitate an eighteenth-century Greek style of handwriting and to produce a document that is so much like Clement that it fools experts who spend their lives analyzing Clement, which quotes a previously lost passage from Mark that is so much like Mark that it fools experts who spend their lives analyzing Mark. If this is forged, it is one of the greatest works of scholarship of the twentieth century, by someone who put an uncanny amount of work into it."[94]

- ^ Some commentators believe that the boy was a stranger, who lived near the garden and, after being awakened, ran out, half-dressed, to see what all the noise was about (vv. 46–49) (See John Gill's Exposition of the Bible, at Bible Study Tools.) W. L. Lane thinks that Mark mentioned this episode in order to make it clear that not only the disciples but "all fled, leaving Jesus alone in the custody of the police."[346]

- ^ In the parallel passages in Matthew and Luke, the word neaniskos is not used. In Matthew 28:2 it is "an angel of the Lord" dressed in white that descends from heaven and "Luke envisions two angelic men" (Luke 24:1–10).[357]

- ^ The expression "the disciple whom Jesus loved" (Greek: ὁ μαθητὴς ὃν ἠγάπα ὁ Ἰησοῦς, ho mathētēs hon ēgapa ho Iēsous) or "the beloved disciple", the disciple "beloved of Jesus" (Greek: ὃν ἐφίλει ὁ Ἰησοῦς, hon efilei ho Iēsous) is mentioned only in the Gospel of John, in six passages: 13:23, 19:26, 20:2, 21:7, 21:20, 21:24.[358]

- ^ For example F. F. Bruce,[383] Raymond E. Brown,[384] Patrick W. Skehan,[119] Robert M. Grant,[122] Helmut Merkel,[385][116] and Frans Neirynck.[125]

- ^ Jesus is said to baptize his followers in John 3:22: "... he spent some time there with them and baptized"; John 3:26: "... he is baptizing, and all are going to him"; and John 4:1: "Jesus is making and baptizing more disciples than John". But in the following verse (John 4:2) the gospel contradicts itself: "—although it was not Jesus himself but his disciples who baptized—" (NRSV).[401]

- ^ "... the audience of the longer Gospel is not catechumens who are preparing for baptism but baptized Christians involved in advanced theological instruction, the goal of which is gnosis."[402]

- ^ Clement of Alexandria, Stromata I.28.176.1–2; IV.1.3.1; V.11.70.7–71.3.[403]

- ^ "The mystery religion language in the letter is metaphorical, as it is in Clement's undisputed writings, and the baptismal imagery in the Gospel is symbolic, as befits a 'mystic gospel.' Unfortunately, Smith misinterpreted this imagery in a literalistic way, as describing a text used as a lection for baptism."[405]

References

[edit]- ^ Schenke 2012, p. 554.

- ^ a b c d e Tselikas 2011

- ^ Burnet 2013, p. 290

- ^ a b c Brown 2005, p. xi.

- ^ Smith 1973, pp. 93–94

- ^ a b Ignatius 1646

- ^ a b c Pantuck & Brown 2008, pp. 107–108

- ^ a b Smith 1973, p. 1

- ^ a b Smith 1973b, p. 13

- ^ a b c d e f Brown 2005, p. 6

- ^ Burke 2013, p. 2

- ^ a b c Burke 2013, p. 5

- ^ Watson 2010, p. 128

- ^ a b c d e f Brown 2005, pp. 25–26

- ^ a b c Hedrick & Olympiou 2000, pp. 8–9

- ^ a b Hedrick 2013, pp. 42–43

- ^ Hedrick 2009, p. 45

- ^ a b Rau 2010, p. 142

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Smith 2011

- ^ Brown 2017, p. 95

- ^ a b Hedrick 2003, p. 133.

- ^ Grafton 2009, p. 25

- ^ a b c Meyer 2003, p. 139.

- ^ a b c d e f g Koester 1990, p. 296.

- ^ a b c Theissen & Merz 1998, p. 46.

- ^ a b c Grafton 2009, p. 26

- ^ a b Brown 2005, p. 68

- ^ a b c Hedrick 2003, p. 141

- ^ Carlson 2013, pp. 306–307

- ^ a b c d Ehrman 2003, pp. 81–82

- ^ a b c d Burke 2013, p. 27

- ^ a b c d Hedrick 2013, p. 31

- ^ a b c Smith 1982, p. 457

- ^ a b c d e f g h Burke 2013, p. 6

- ^ Hedrick 2013, p. 44

- ^ a b c d e Burke 2013, p. 9