1945 Canadian federal election

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

245 seats in the House of Commons 123 seats needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opinion polls | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 75.3%[1] ( | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

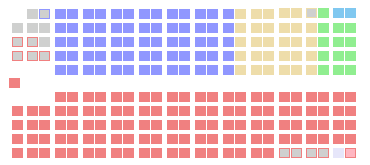

The Canadian parliament after the 1945 election | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The 1945 Canadian federal election was held on June 11, 1945, to elect members of the House of Commons of the 20th Parliament of Canada. Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King's Liberals won a third term. The party fell five seats short of a majority but was able to rule as a majority government with the support of Independent Liberal MPs.

Since 1939, Canada had been fighting in World War II. In May 1945, the war in Europe ended, allowing King to call an election. As the war in Asia was still raging on, King promised a voluntary force to fight in Operation Downfall, the planned invasion of Japan, while Progressive Conservative Party (PC Party) leader John Bracken promised conscription, which was an unpopular proposal and led to the PCs' third consecutive defeat. The Liberals were also re-elected because of their promise to expand welfare programs. However, they also lost about a third of their seats; this stark decline in support was partly attributed to their introduction of conscription in 1944 (which was unpopular in Quebec, paving the rise of the Bloc Populaire)[2] as well as the breakthrough of the democratic socialist Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), which campaigned on an even bigger expansion of the welfare state than the Liberals. The Social Credit Party made modest gains.

Although the election officially resulted in a minority government, the election of eight "Independent Liberal" MPs, most of whom did not run as official Liberals because of their opposition to conscription, gave the King government an effective working majority in parliament. Most of the Independent Liberal MPs joined (or re-joined) the Liberal caucus following World War II when the conscription issue became moot. As King was defeated in his own riding of Prince Albert, fellow Liberal William MacDiarmid, who was re-elected in the safe seat of Glengarry, resigned so that a by-election could be held, which was subsequently won by King.[3]

Background

[edit]In the 1935 election, the Liberal Party led by William Lyon Mackenzie King returned to power (King's Liberals had previously governed Canada from 1921 to 1930) with a landslide majority government. The King government's success in combatting the Great Depression led to their second landslide majority victory in the 1940 election. From 1939 to 1945, the King government's main priority was aiding the Allies in World War II.

In the period leading up to the election, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation was rising in popularity. A Gallup poll from September 1943 showed the CCF with a one-point lead over both the Liberals and Progressive Conservatives. Many predicted a major breakthrough for the CCF nationally and the party was expected to win 70 to 100 seats, possibly even enough to form a minority government. In the Saskatchewan provincial election, the CCF won a landslide victory, forming a provincial government for the first time.

In 1942, members of the Conservative Party held the Port Hope Conference, which established several Conservative goals including support for free enterprise and conscription, and more radical policies such as full-employment, low-cost housing, trade union rights, as well as a whole range of social security measures, including a government financed medicare system. Progressive Party Premier of Manitoba John Bracken became the Conservative Party's leader that same year, and changed the party's name to the Progressive Conservative Party as a result of this policy shift.[4]

Campaign

[edit]Liberals

[edit]A key issue in this election seems to have been electing a stable government. The Liberals urged voters to "Return the Mackenzie King Government", and argued that only the Liberal Party had a "preponderance of members in all nine provinces". Mackenzie King threatened to call a new election if he was not given a majority: "We would have confusion to deal with at a time when the world will be in a very disturbed situation. The war in Europe is over, but unrest in the east is not over."

Social welfare programs were also an issue in the campaign. Another Liberal slogan encouraged voters to "Build a New Social Order" by endorsing the Liberal platform, which included

- $750 million to provide land, jobs and business support for veterans;

- $400 million of public spending to build housing;

- $250 million for family allowances;

- establishing an Industrial development Bank;

- loans to farmers, floor prices for agricultural products;

- tax reductions.

Progressive Conservatives

[edit]The Progressive Conservatives tried to capitalize on the massive mid-campaign victory by the Ontario Progressive Conservative Party in the 1945 Ontario provincial election. PC campaign ads exhorted voters to rally behind their party: "Ontario shows! Only Bracken can win!", and suggesting that it would be impossible to form a majority government in the country without a plurality of seats in Ontario, which only the Tories could win.

Operation Downfall, the invasion of Japan, was scheduled for late 1945-early 1946. Bracken had promised conscription for the invasion of Japan whereas King had promised to commit one division of volunteers to the planned invasion of Japan.[5] Based on the way that the Japanese had fought the battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa it was widely expected that the invasion of the Japanese home islands would be a bloody campaign, and Bracken's promise of conscription for the planned invasion of Japan did much to turn voters against his party.[5]

Despite the party's performance ultimately being their best since R.B. Bennett's government was ousted in a landslide a decade previously, Bracken was widely held responsible for their failure to make a better showing – aside from the conscription issue, many believed that his western populism was a futile approach, and that the Tories could not hope to compete with the CCF and Socreds in the west – and the party grandees immediately began pressuring him to resign in favour of George A. Drew, who had led the Ontario Progressive Conservatives to their provincial election victory; Bracken would eventually do so in 1948.

Co-operative Commonwealth Federation

[edit]Campaigning under the slogan, "Work, Security, and Freedom for All – with the CCF", the CCF promised to retain war-time taxes on high incomes and excess profits in order to fund social services, and to abolish the Senate of Canada. The CCF fought hard to prevent the support of labour from going to the Labor-Progressive Party (i.e., the Communist Party of Canada).

The LPP, for its part, pointed out that the CCF's refusal to enter into an electoral pact with the LPP had cost the CCF 100,000 votes in the Ontario election, and had given victory to the Ontario PCs. It urged voters to "Make Labour a Partner in Government."

Social Credit

[edit]The Social Credit Party of Canada tried, with modest success, to capitalize on the positive image of the Alberta Socred government of William Aberhart, asking voters, "Good Government in Alberta -- Why Not at Ottawa?". Referring to social credit monetary theories, the party encouraged voters to "Vote for the National Dividend".

Opinion polling

[edit]| Polling firm | Last day of survey |

Source | LPC | PC | CCF | SC | BP | Other | ME | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Election 1945 | June 11, 1945 | 39.78 | 27.62 | 15.55 | 4.05 | 3.29 | 5.42 | |||

| Gallup | June 9, 1945 | [6] | 39 | 29 | 17 | 4 | 5[7] | 6[a] | — | — |

| Gallup | April 1945 | [7] | 36 | 29 | 20 | 4[6] | 6 | 5[a] | — | — |

| Gallup | January 1945 | [7] | 36 | 28 | 22 | 4[6] | 6 | 4[a] | — | — |

| Gallup | November 1944 | [8] | 36 | 28 | 23 | — | 5 | 8 | — | — |

| Gallup | September 1944 | [8] | 36 | 27 | 24 | 4[6] | 5 | 4[a] | — | — |

| Gallup | June 1944 | [8] | 35 | 30 | 21 | — | 7 | 7 | — | — |

| Gallup | March 1944 | [8] | 34 | 30 | 22 | — | 8 | 6 | — | — |

| Gallup | January 1944 | [8] | 31 | 29 | 24 | 3[6] | 9 | 4[a] | — | — |

| Gallup | December 1943 | [9] | 31 | 29 | 26 | — | 8 | 6 | — | — |

| Gallup | September 1943 | [10] | 28 | 28 | 29 | 3[6] | 9 | 3[a] | — | — |

| Gallup | June 1943 | [10] | 35 | 31 | 21 | — | 8 | 5 | — | — |

| Gallup | May 1943 | [10] | 36 | 28 | 21 | — | 10 | 5 | — | — |

| Gallup | February 1943 | [10] | 32 | 27 | 23 | — | 7 | 11 | — | — |

| Gallup | December 1942 | [10] | 36 | 24 | 23 | — | — | 17 | — | — |

| Bloc populaire founded (September 8, 1942) | ||||||||||

| Gallup | September 1942 | [11] | 39 | 23 | 21 | 6 | — | 11 | — | — |

| Gallup | January 1942 | [6] | 55 | 30 | 10 | 2 | — | 3 | — | — |

| Election 1940 | March 26, 1940 | 51.32 | 29.24 | 8.42 | 2.59 | |||||

National results

[edit]

| Party | Party leader | # of candidates |

Seats | Popular vote | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1940 | Elected | % Change | # | % | pp Change | ||||

| Liberal | W. L. Mackenzie King | 236 | 177 | 118 | -33.9% | 2,086,545 | 39.78% | -11.54 | |

| Progressive Conservative1 | John Bracken | 203 | 39 | 66 | +66.7% | 1,448,744 | 27.62% | -2.79 | |

| Co-operative Commonwealth | M. J. Coldwell | 205 | 8 | 28 | +250% | 815,720 | 15.55% | +7.31 | |

| Social Credit2 | Solon Earl Low | 93 | 10 | 13 | +30.0% | 212,220 | 4.05% | +1.46 | |

| Independent Liberal | 20 | 2 | 8 | +300% | 93,791 | 1.79% | -1.40 | ||

| Independent | 64 | 1 | 6 | +500% | 256,381 | 4.89% | +3.65 | ||

| Bloc populaire | Maxime Raymond | 35 | * | 2 | * | 172,765 | 3.29% | * | |

| Labor–Progressive3 | Tim Buck | 68 | 16 | 16 | 111,892 | 2.13% | +1.94 | ||

| Independent PC | 8 | * | 1 | * | 14,541 | 0.28% | * | ||

| Independent CCF4 | 2 | * | 1 | * | 6,402 | 0.12% | * | ||

| Liberal–Progressive | 1 | 3 | 1 | -66.7% | 6,147 | 0.12% | -0.48 | ||

| National Government5 | 1 | - | 4,872 | 0.09% | |||||

| Trades Union | 1 | * | - | * | 4,679 | 0.09% | * | ||

| Farmer-Labour | 2 | - | - | - | 3,620 | 0.07% | -0.11 | ||

| Independent Conservative | 1 | - | - | -100% | 2,653 | 0.05% | -0.18 | ||

| Democratic | W.R.N. Smith | 5 | * | - | * | 2,603 | 0.05% | * | |

| Union of Electors | 1 | * | - | * | 596 | 0.01% | * | ||

| Socialist Labour | 2 | * | - | * | 459 | 0.01% | * | ||

| Labour | 1 | - | - | - | 423 | 0.01% | -0.07 | ||

| Liberal-Labour | 1 | * | - | * | 345 | 0.01% | * | ||

| Independent Labour | 1 | * | - | * | 241 | x | * | ||

| Farmer | 1 | - | - | - | 70 | x | x | ||

| Total | 952 | 245 | 245 | - | 5,245,709 | 100% | |||

| Sources: http://www.elections.ca -- History of Federal Ridings since 1867 | |||||||||

Notes:

* The party did not nominate candidates in the previous election.

x - less than 0.005% of the popular vote.

1 1945 Progressive Conservative vote compared to 1940 National Government + Conservative vote.

2 1945 Social Credit vote compared to 1940 New Democracy + Social Credit vote.

3 1945 Labor-Progressive vote compared to 1940 Communist vote.

4 The successful "Independent CCF" candidate ran as a People's Co-operative Commonwealth Federation candidate.

5 One Progressive Conservative candidate ran under the "National Government" label that the party had used in the 1940 election.

6 MP Dorise Nielsen was elected in 1940 as a Unity candidate in North Battleford. She joined the Labor-Progressive Party in 1943 and ran for re-election in 1945 as an LPP MP and lost. Fred Rose was elected to parliament for Cartier as a Labor-Progressive MP in a 1943 by-election. He was re-elected in 1945.

Vote and seat summaries

[edit]

Results by province

[edit]| Party name | BC | AB | SK | MB | ON | QC | NB | NS | PE | YK | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal | Seats: | 5 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 34 | 47 | 7 | 9 | 3 | 118 | ||

| Popular Vote: | 27.5 | 21.8 | 33.0 | 32.7 | 40.8 | 46.5 | 50.0 | 45.7 | 48.4 | 39.8 | |||

| Progressive Conservative | Seats: | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 48 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 66 | |

| Vote: | 30.0 | 18.7 | 18.8 | 24.9 | 41.4 | 9.7 | 38.3 | 36.8 | 47.4 | 40.0 | 27.6 | ||

| Co-operative Commonwealth | Seats: | 4 | - | 18 | 5 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 28 | |

| Vote: | 29.4 | 18.4 | 44.4 | 31.6 | 14.3 | 2.4 | 7.4 | 16.7 | 4.2 | 27.5 | 15.6 | ||

| Social Credit | Seats: | - | 13 | - | - | - | - | 13 | |||||

| Vote: | 2.3 | 36.6 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 0.2 | 4.4 | 4.0 | ||||||

| Independent Liberal | Seats: | 1 | 7 | - | 8 | ||||||||

| Vote: | 1.7 | 5.9 | 1.1 | 1.8 | |||||||||

| Independent | Seats: | - | - | 6 | - | - | 6 | ||||||

| Vote: | 0.8 | 0.4 | 16.9 | 3.2 | 0.2 | 4.9 | |||||||

| Bloc populaire | Seats: | - | 2 | 2 | |||||||||

| Vote: | 0.3 | 11.9 | 3.3 | ||||||||||

| Labor–Progressive | Seats: | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | |||

| Vote: | 5.9 | 4.5 | 0.8 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 32.4 | 2.1 | ||||

| Independent PC | Seats: | - | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Vote: | xx | 1.0 | 0.3 | ||||||||||

| Independent CCF | Seats: | 1 | - | 1 | |||||||||

| Vote: | 1.4 | xx | 0.1 | ||||||||||

| Liberal-Progressive | Seats: | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Vote: | 1.9 | 0.1 | |||||||||||

| Total Seats | 16 | 17 | 21 | 17 | 82 | 65 | 10 | 12 | 4 | 1 | 245 | ||

| Parties that won no seats: | |||||||||||||

| National Government | Vote: | 0.3 | 0.1 | ||||||||||

| Trades Union | Vote: | 1.1 | 0.1 | ||||||||||

| Farmer-Labour | Vote: | 0.2 | 0.1 | ||||||||||

| Independent Conservative | Vote: | 0.2 | 0.1 | ||||||||||

| Democratic | Vote: | 0.6 | xx | ||||||||||

| Union of Electors | Vote: | xx | xx | ||||||||||

| Socialist Labour | Vote: | 0.1 | xx | ||||||||||

| Labour | Vote: | xx | xx | ||||||||||

| Liberal-Labour | Vote: | xx | xx | ||||||||||

| Independent Labour | Vote: | 0.1 | xx | ||||||||||

| Farmer | Vote: | xx | xx | ||||||||||

xx - less than 0.05% of the popular vote.

See also

[edit]- List of Canadian federal general elections

- List of political parties in Canada

- 20th Canadian Parliament

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Voter Turnout at Federal Elections and Referendums". Elections Canada. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Neatby, H. Blair (2016). "King, William Lyon Mackenzie". In Cook, Ramsay; Bélanger, Réal (eds.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. XVII (1941–1950) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ Neatby, H. Blair (2016). "King, William Lyon Mackenzie". In Cook, Ramsay; Bélanger, Réal (eds.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. XVII (1941–1950) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ^ The Essentials of Canadian History: Pre-colonization to 1867-the Beginning ... – Terence Allan Crowley, Rae Murphy – Google Boeken. Books.google.com. Retrieved on April 12, 2014.

- ^ a b Morton, Desmond A Military History of Canada, Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1999 page 223-224.

- ^ a b c d e f g "No Notable Shift in Party Support". The Evening Citizen. March 1, 1947. p. 1.

- ^ a b c The Quarter's Polls. (1945). Public Opinion Quarterly, 9(4), 510. doi:10.1086/265765

- ^ a b c d e Public Opinions Polls. (1944). Public Opinion Quarterly, 8(4), 580

- ^ Public Opinions Polls. (Spring 1944). Public Opinion Quarterly, 8(1), 142 doi:10.1086/265676

- ^ a b c d e Public Opinions Polls. (1943). Public Opinion Quarterly, 7(4), 492 doi:10.1086/265660

- ^ Gallup and Fortune Polls. (1942). Public Opinion Quarterly, 6(4), 650. doi:10.1086/265589

Further reading

[edit]- LeDuc, Lawrence; Pammett, Jon H.; McKenzie, Judith L.; Turcotte, André (2010). Dynasties and Interludes: Past and Present in Canadian Electoral Politics. Toronto: Dundurn Press. ISBN 978-1-55488-886-3.

- Beck, James Murray (1968). Pendulum of Power; Canada's Federal Elections. Scarborough: Prentice-Hall of Canada. ISBN 978-0-13-655670-1.

- Argyle, Ray (2004). Turning Points: The Campaigns that Changed Canada 2004 and Before. Toronto: White Knight Publications. ISBN 978-0-9734186-6-8.