Gaza Strip

Gaza Strip قطاع غزة | |

|---|---|

| Status |

|

| Capital | Gaza City 31°30′53″N 34°27′15″E / 31.51472°N 34.45417°E |

| Largest city | Rafah[d][7] |

| Official languages | Arabic |

| Ethnic groups | Palestinian Arabs |

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) | Gazan Palestinian |

| Government | |

• Hamas Chief in the Gaza Strip[8] | Mohammed Sinwar |

| Essam al-Da'alis | |

| Area | |

• Total | 365 km2 (141 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | 2,141,643[9] |

• Density | 5,967.5/km2 (15,455.8/sq mi) |

| Currency | Israeli new shekel Egyptian pound[10] |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (Palestine Standard Time) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (Palestine Summer Time) |

| Calling code | +970 |

| ISO 3166 code | PS |

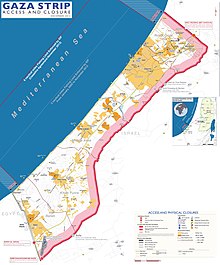

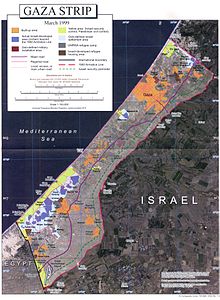

The Gaza Strip (/ˈɡɑːzə/ ;[11] Arabic: قِطَاعُ غَزَّةَ Qiṭāʿ Ġazzah [qɪˈtˤɑːʕ ˈɣaz.za]), also known simply as Gaza, is a small territory located on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea; it is the smaller of the two Palestinian territories, the other being the West Bank, that make up the State of Palestine. Inhabited by mostly Palestinian refugees and their descendants, Gaza is one of the most densely populated territories in the world. Gaza is bordered by Egypt on the southwest and Israel on the east and north. The territory has been under Israeli occupation since 1967.[12]

The territorial boundaries were established while Gaza was controlled by Egypt at the conclusion of the 1948 Arab–Israeli war, and it became a refuge for Palestinians who fled or were expelled during the 1948 Palestine war.[13][14] Later, during the 1967 Six-Day War, Israel captured and occupied the Gaza Strip, initiating its decades-long military occupation of the Palestinian territories.[13][14] The mid-1990s Oslo Accords established the Palestinian Authority (PA) as a limited governing authority, initially led by the secular party Fatah until that party's electoral defeat in 2006 to the Sunni Islamic Hamas. Hamas would then take over the governance of Gaza in a battle the next year,[15][16] subsequently warring with Israel.

The restrictions on movement and goods in Gaza imposed by Israel date back to the early 1990s.[17] In 2005, Israel unilaterally withdrew its military forces from Gaza, dismantled its settlements, and implemented a temporary blockade of Gaza.[18] The blockade became indefinite after the 2007 Hamas takeover.[19][18] Egypt also began its blockade of Gaza in 2007.

Despite the Israeli disengagement, Gaza is still considered occupied by Israel under international law.[20][21] The current blockade prevents people and goods from freely entering or leaving the territory, leading to Gaza often being called an "open-air prison".[22][23] The UN, as well as at least 19 human-rights organizations, have urged Israel to lift the blockade.[24] Israel has justified its blockade on the strip with wanting to stop flow of arms, but Palestinians and rights groups say it amounts to collective punishment and exacerbates dire living conditions. Prior to the Israel–Hamas war, Hamas had said that it did not want a military escalation in Gaza partially to prevent exacerbating the humanitarian crisis after the 2021 conflict.[25] A tightened blockade since the start of the Israel–Hamas war has contributed to an ongoing famine.[26]

The Gaza Strip is 41 kilometres (25 miles) long, from 6 to 12 km (3.7 to 7.5 mi) wide, and has a total area of 365 km2 (141 sq mi).[27][9] With around 2 million Palestinians[9] on approximately 365 km2 (141 sq mi) of land, Gaza has one of the world's highest population densities.[28][29] More than 70% of Gaza's population are Palestinian refugees, half of whom are under the age of 18.[30] Sunni Muslims make up most of Gaza's population, with a Palestinian Christian minority. Gaza has an annual population growth rate of 1.99% (2023 est.), the 39th-highest in the world.[9] Gaza's unemployment rate is among the highest in the world, with an overall unemployment rate of 46% and a youth unemployment rate of 70%.[19][31] Despite this, the area's 97% literacy rate is higher than that of nearby Egypt, while youth literacy is 88%.[32] Gaza has throughout the years been seen as a source of Palestinian nationalism and resistance.[33][34][35]

|

|

History

Historically part of the Palestine region, the area was controlled since the 16th century by the Ottoman Empire; in 1906, the Ottomans and the British Empire set the region's international border with Egypt.[36] With the defeat of the Central Powers in World War I and the subsequent partition of the Ottoman Empire, the British deferred the governance of the Gaza Strip area to Egypt, which declined the responsibility.[37] Britain itself kept and ruled the territory it occupied in 1917–18, from 1920 until 1948 under the internationally accepted frame of "Mandatory Palestine".

1948–1959: All-Palestine government

During the 1948 Palestine war and more specifically the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, tens of thousands of Palestinian refugees fled or were expelled to the Gaza Strip.[38] By the end of the war, 25% of Mandatory Palestine's Arab population was in Gaza, though the Strip constituted only 1% of the land.[39] The same year, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) was established to administer various refugee programmes.[40]

On 22 September 1948 (near the end of the Arab–Israeli War), in the Egyptian-occupied Gaza City, the Arab League proclaimed the All-Palestine Government, partly to limit Transjordan's influence over Palestine. The All-Palestine Protectorate was quickly recognized by six of the Arab League's then-seven members (excluding Transjordan): Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen.[41]

After the cessation of hostilities, the Israel–Egypt Armistice Agreement of 24 February 1949 established the line of separation between Egyptian and Israeli forces, as well as the modern boundary between Gaza and Israel, which both signatories declared not to be an international border. The southern border with Egypt was unchanged.[36]

Palestinians living in Gaza or Egypt were issued All-Palestine passports. Egypt did not offer them citizenship. From the end of 1949, they received aid directly from UNRWA. During the Suez Crisis (1956), Gaza and the Sinai Peninsula were occupied by Israeli troops, who withdrew under international pressure. The All-Palestine government was accused of being little more than a façade for Egyptian control, with negligible independent funding or influence. It subsequently moved to Cairo and dissolved in 1959 by decree of Egyptian President Gamal Abdul Nasser.[citation needed]

1956–1957: Israeli occupation

During the 1956 Suez Crisis (the Second Arab–Israeli war), Israel invaded Gaza and the Sinai Peninsula. On 3 November, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) attacked Egyptian and Palestinian forces at Khan Yunis.[42] The city of Khan Yunis resisted being captured, and Israel responded with a heavy bombing campaign that inflicted heavy civilian casualties.[43] After a fierce battle, the Israeli 37th Armored Brigade's Sherman tanks broke through the heavily fortified lines outside of Khan Yunis held by the 86th Palestinian Brigade.[44]

After some street-fighting with Egyptian soldiers and Palestinian fedayeen, Khan Yunis fell to the Israelis.[44] Upon capturing Khan Yunis, the IDF committed an alleged massacre.[45] Israeli troops started executing unarmed Palestinians, mostly civilians; in one instance men were lined up against walls in central square and executed with machine guns.[46] The claims of a massacre were reported to the United Nations General Assembly on 15 December 1956 by UNRWA director Henry Labouisse, who reported from "trustworthy sources" that 275 people were killed in the massacre, of which 140 were refugees and 135 local residents.[47][48]

On 12 November, days after the hostilities had ended, Israel killed 111 people in the Rafah refugee camp during Israeli operations, provoking international criticism.[49][45]

Israel ended the occupation in March 1957, amid international pressure. During the four-month Israeli occupation, 900–1,231 people were killed.[50] According to French historian Jean-Pierre Filiu, 1% of the population of Gaza was killed, wounded, imprisoned or tortured during the occupation.[50]

1959–1967: Egyptian occupation

After the dissolution of the All-Palestine Government in 1959, under the excuse of pan-Arabism, Egypt continued to occupy Gaza until 1967. Egypt never annexed the Strip, but instead treated it as a controlled territory and administered it through a military governor.[51] The influx of over 200,000 refugees from former Mandatory Palestine, roughly a quarter of those who fled or were expelled from their homes during, and in the aftermath of, the 1948 Arab–Israeli War into Gaza[52] resulted in a dramatic decrease in the standard of living. Because the Egyptian government restricted movement to and from Gaza, its inhabitants could not look elsewhere for gainful employment.[53]

1967: Israeli occupation

In June 1967, during the Six-Day War, IDF captured Gaza. Under the then head of Israel's Southern Command Ariel Sharon, dozens of Palestinians, suspected of being members of the resistance, were executed without trial.[54]

Between 1967 and 1968, Israel evicted approximately 75,000 residents of the Gaza Strip who Golda Meir described as a "fifth column". In addition, at least 25,000 Gazan residents were prevented from returning after the 1967 war. Ultimately, the Strip lost 25% (a conservative estimate) of its prewar population between 1967 and 1968.[55] In 1970-1971 Ariel Sharon implemented what became known as a 'five finger' strategy, which consisted in creating military areas and settlements by breaking the Strip into five zones to better enable Israeli occupation, settlement and, by discontinuous fragmentation of the Palestinian zones created, allow an efficient management of the area. Thousands of homes were bulldozed and large numbers of Bedouin families were exiled to the Sinai.[56][57][58]

Between 1973 (after the Yom Kippur War) and 1987, official policy on economic development in the Gaza Strip remained the same as in 1969 with limited local investment and economic opportunity coming primarily from employment in Israel.[59]

According to Tom Segev, moving the Palestinians out of the country had been a persistent element of Zionist thinking from early times.[60] In December 1967, during a meeting at which the Security Cabinet brainstormed about what to do with the Arab population of the newly occupied territories, one of the suggestions Prime Minister Levi Eshkol proffered regarding Gaza was that the people might leave if Israel restricted their access to water supplies.[61] A number of measures, including financial incentives, were taken shortly afterwards to begin to encourage Gazans to emigrate elsewhere.[60][62] Following the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, "various international agencies struggled to respond" and American Near East Refugee Aid was founded to help victims of the conflict by providing immediate emergency relief.[63]

Subsequent to this military victory, Israel created the first Israeli settlement bloc in the Strip, Gush Katif, in the southwest corner near Rafah and the Egyptian border on a spot where a small kibbutz had previously existed for 18 months between 1946 and 1948. The kibbutz community had been established as part of the Jewish Agency's "11 points in the Negev" plan, in which 11 Jewish villages were built across the Negev in a single night as a response to the Morrison-Grady Plan, which threatened to exclude the Negev from a future Jewish State. In total, between 1967 and 2005, Israel established 21 settlements in Gaza, comprising 20% of the total territory. The economic growth rate from 1967 to 1982 averaged roughly 9.7 percent per annum, due in good part to expanded income from work opportunities inside Israel, which had a major utility for the latter by supplying the country with a large unskilled and semi-skilled workforce. Gaza's agricultural sector was adversely affected as one-third of the Strip was appropriated by Israel, competition for scarce water resources stiffened, and the lucrative cultivation of citrus declined with the advent of Israeli policies, such as prohibitions on planting new trees and taxation that gave breaks to Israeli producers, factors which militated against growth. Gaza's direct exports of these products to Western markets, as opposed to Arab markets, was prohibited except through Israeli marketing vehicles, in order to assist Israeli citrus exports to the same markets. The overall result was that large numbers of farmers were forced out of the agricultural sector. Israel placed quotas on all goods exported from Gaza, while abolishing restrictions on the flow of Israeli goods into the Strip. Sara Roy characterised the pattern as one of structural de-development.[59]

On 26 March 1979, Israel and Egypt signed the Egypt–Israel peace treaty.[64] Among other things, the treaty provided for the withdrawal by Israel of its armed forces and civilians from the Sinai Peninsula, which Israel had captured during the Six-Day War. The Egyptians agreed to keep the Sinai Peninsula demilitarized. The final status of the Gaza Strip, and other relations between Israel and Palestinians, was not dealt with in the treaty. Egypt renounced all territorial claims to territory north of the international border. The Gaza Strip remained under Israeli military administration. The Israeli military became responsible for the maintenance of civil facilities and services.

After the 1979 Egypt–Israel peace treaty, a 100-meter-wide buffer zone between Gaza and Egypt known as the Philadelphi Route was established. The international border along the Philadelphi corridor between Egypt and Gaza is 11 kilometres (7 miles) long.

1987: First Intifada

The First Intifada was a sustained series of protests and violent riots carried out by Palestinians in the Israeli-occupied Palestinian territories and Israel.[65] It was motivated by collective Palestinian frustration over Israel's military occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, as it approached a twenty-year mark, having begun after Israel's victory in the 1967 Arab–Israeli War.[66] The uprising lasted from December 1987 until the Madrid Conference of 1991, though some date its conclusion to 1993, with the signing of the Oslo Accords.

The intifada began on 9 December 1987,[66] in the Jabalia refugee camp of the Gaza Strip after an Israeli army truck collided with a civilian car, killing four Palestinian workers.[67] Palestinians charged that the collision was a deliberate response for the killing of an Israeli in Gaza days earlier.[68] Israel denied that the crash, which came at time of heightened tensions, was intentional or coordinated.[69] The Palestinian response was characterized by protests, civil disobedience, and violence.[70][71] There was graffiti, barricading,[72][73] and widespread throwing of stones and Molotov cocktails at the IDF and its infrastructure within the West Bank and Gaza Strip. These contrasted with civil efforts including general strikes, boycotts of Israeli Civil Administration institutions in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, an economic boycott consisting of refusal to work in Israeli settlements on Israeli products, refusal to pay taxes, and refusal to drive Palestinian cars with Israeli licenses.[70][71][72]

1994: Gaza under Palestinian Authority

In May 1994, following the Palestinian-Israeli agreements known as the Oslo Accords, a phased transfer of governmental authority to the Palestinians took place. Much of the Strip came under Palestinian control, except for the settlement blocs and military areas. The Israeli forces left Gaza City and other urban areas, leaving the new Palestinian Authority to administer and police those areas. The Palestinian Authority, led by Yasser Arafat, chose Gaza City as its first provincial headquarters. In September 1995, Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) signed a second agreement, extending the Palestinian Authority to most West Bank towns.

Between 1994 and 1996, Israel built the Gaza–Israel barrier to improve security in Israel. The barrier was largely torn down by Palestinians at the beginning of the Second Intifada in September 2000.[74]

2000: Second Intifada

The Second Intifada was a major Palestinian uprising in the Israeli-occupied Palestinian territories and Israel. The general triggers for the unrest are speculated to have been centred on the failure of the 2000 Camp David Summit, which was expected to reach a final agreement on the Israeli–Palestinian peace process in July 2000.[75] Outbreaks of violence began in September 2000, after Ariel Sharon, then the Israeli opposition leader, made a provocative visit to the Al-Aqsa compound on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem;[75] the visit itself was peaceful, but, as anticipated, sparked protests and riots that Israeli police put down with rubber bullets and tear gas.[76] The Second Intifada also marked the beginning of rocket attacks and bombings of Israeli border localities by Palestinian guerrillas from the Gaza Strip, especially by the Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad movements.

High numbers of casualties were caused among civilians as well as combatants. Israeli forces engaged in gunfire, targeted killings, and tank and aerial attacks, while Palestinians engaged in suicide bombings, gunfire, stone-throwing, and rocket attacks.[77][78] Palestinian suicide bombings were a prominent feature of the fighting and mainly targeted Israeli civilians, contrasting with the relatively less violent nature of the First Intifada.[79][80] With a combined casualty figure for combatants and civilians, the violence is estimated to have resulted in the deaths of approximately 3,000 Palestinians and 1,000 Israelis, as well as 64 foreigners.[81]

Between December 2000 and June 2001, the barrier between Gaza and Israel was reconstructed. A barrier on the Gaza Strip-Egypt border was constructed starting in 2004.[82] The main crossing points are the northern Erez Crossing into Israel and the southern Rafah Crossing into Egypt. The eastern Karni Crossing used for cargo, closed down in 2011.[83] Israel controls the Gaza Strip's northern borders, as well as its territorial waters and airspace. Egypt controls Gaza Strip's southern border, under an agreement between it and Israel.[84] Neither Israel or Egypt permits free travel from Gaza as both borders are heavily militarily fortified. "Egypt maintains a strict blockade on Gaza in order to isolate Hamas from Islamist insurgents in the Sinai."[85]

2005: Israel's unilateral disengagement

In 2005, Israel withdrew from the Gaza Strip and dismantled its settlements.[86] Israel also withdrew from the Philadelphi Route, a narrow strip of land adjacent to the border with Egypt, after Egypt agreed to secure its side of the border after the Agreement on Movement and Access, known as the Rafah Agreement.[87] The Gaza Strip was left under the control of the Palestinian Authority.[88]

Post-2006: Hamas takeover

In the Palestinian parliamentary elections held on 25 January 2006, Hamas won a plurality of 42.9% of the total vote and 74 out of 132 total seats (56%).[89][90] When Hamas assumed power the next month, Israel, the United States, the EU, Russia and the UN demanded that Hamas accept all previous agreements, recognize Israel's right to exist, and renounce violence; when Hamas refused,[91] they cut off direct aid to the Palestinian Authority, although some aid money was redirected to humanitarian organizations not affiliated with the government.[92] The resulting political disorder and economic stagnation led to many Palestinians emigrating from the Gaza Strip.[93]

In January 2007, fighting erupted between Hamas and Fatah. The deadliest clashes occurred in the northern Gaza Strip. On 30 January 2007, a truce was negotiated between Fatah and Hamas.[94] After a few days, new fighting broke out. On 1 February, Hamas killed 6 people in an ambush on a Gaza convoy which delivered equipment for Abbas' Palestinian Presidential Guard.[95] Fatah fighters stormed a Hamas-affiliated university in the Gaza Strip. Officers from Abbas' presidential guard battled Hamas gunmen guarding the Hamas-led Interior Ministry.[96] In May 2007, new fighting broke out between the factions.[97] Interior Minister Hani Qawasmi, who had been considered a moderate civil servant acceptable to both factions, resigned due to what he termed harmful behavior by both sides.[98]

Fighting spread in the Gaza Strip, with both factions attacking vehicles and facilities of the other side. Following a breakdown in an Egyptian-brokered truce, Israel launched an air strike which destroyed a building used by Hamas. Ongoing violence prompted fear that it could bring the end of the Fatah-Hamas coalition government, and possibly the end of the Palestinian authority.[99] Hamas spokesman Moussa Abu Marzouk blamed the conflict between Hamas and Fatah on Israel, stating that the constant pressure of economic sanctions resulted in the "real explosion."[100] From 2006 to 2007 more than 600 Palestinians were killed in fighting between Hamas and Fatah.[101] 349 Palestinians were killed in fighting between factions in 2007. 160 Palestinians killed each other in June alone.[102]

2007: Fatah–Hamas conflict

Following the victory of Hamas in the 2006 Palestinian legislative election, Hamas and Fatah formed the Palestinian authority national unity government headed by Ismail Haniyeh. Shortly after, Hamas took control of the Gaza Strip in the course of the Battle of Gaza (June 2007),[103] seizing government institutions and replacing Fatah and other government officials with its own.[104] By 14 June, Hamas fully controlled the Gaza Strip. Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas responded by declaring a state of emergency, dissolving the unity government and forming a new government without Hamas participation. PNA security forces in the West Bank arrested a number of Hamas members.

In late June 2008, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Jordan declared the West Bank-based cabinet formed by Abbas as "the sole legitimate Palestinian government". Egypt moved its embassy from Gaza to the West Bank.[105] Saudi Arabia and Egypt supported reconciliation and a new unity government and pressed Abbas to start talks with Hamas. Abbas had always conditioned this on Hamas returning control of the Gaza Strip to the Palestinian Authority. After the takeover, Israel and Egypt closed their border crossings with Gaza. Palestinian sources reported that European Union monitors fled the Rafah Border Crossing, on the Gaza–Egypt border for fear of being kidnapped or harmed.[106] Arab foreign ministers and Palestinian officials presented a united front against control of the border by Hamas.[107] Meanwhile, Israeli and Egyptian security reports said that Hamas continued smuggling in large quantities of explosives and arms from Egypt through tunnels. Egyptian security forces uncovered 60 tunnels in 2007.[108]

Egyptian border barrier breach

On 23 January 2008, after months of preparation during which the steel reinforcement of the border barrier was weakened,[109] Hamas destroyed several parts of the wall dividing Gaza and Egypt in the town of Rafah. Hundreds of thousands of Gazans crossed the border into Egypt seeking food and supplies. Due to the crisis, Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak ordered his troops to allow the Palestinians in but to verify that they did not bring weapons back across the border.[110] Egypt arrested and later released several armed Hamas militants in the Sinai who presumably wanted to infiltrate into Israel. At the same time, Israel increased its state of alert along the length of the Israel–Egypt Sinai border, and warned its citizens to leave Sinai "without delay."

In February 2008, the Israel–Gaza conflict intensified, with rockets launched at Israeli cities. Aggression by Hamas led to Israeli military action on 1 March 2008, resulting in over 110 Palestinians being killed according to BBC News, as well as 2 Israeli soldiers. Israeli human rights group B'Tselem estimated that 45 of those killed were not involved in hostilities, and 15 were minors.[111]

2008–2009: Gaza War

On 27 December 2008,[112] Israeli F-16 fighters launched a series of air strikes against targets in Gaza following the breakdown of a temporary truce between Israel and Hamas.[113] Israel began a ground invasion of the Gaza Strip on 3 January 2009.[114] Various sites that Israel claimed were being used as weapons depots were struck from the air : police stations, schools, hospitals, UN warehouses, mosques, various Hamas government buildings and other buildings.[115]

Israel said that the attack was a response to Hamas rocket attacks on southern Israel, which totaled over 3,000 in 2008, and which intensified during the few weeks preceding the operation. Israel advised people near military targets to leave before the attacks. Israeli defense sources said that Defense Minister Ehud Barak instructed the IDF to prepare for the operation six months before it began, using long-term planning and intelligence-gathering.[116]

A total of 1,100–1,400[117] Palestinians (295–926 civilians) and 13 Israelis were killed in the 22-day war.[118] The conflict damaged or destroyed tens of thousands of homes,[119][120] 15 of Gaza's 27 hospitals and 43 of its 110 primary health care facilities,[121] 800 water wells,[122] 186 greenhouses,[123] and nearly all of its 10,000 family farms;[124] leaving 50,000 homeless,[125] 400,000–500,000 without running water,[125][126] one million without electricity,[126] and resulting in acute food shortages.[127] The people of Gaza still suffer from the loss of these facilities and homes, especially since they have great challenges to rebuild them.

2014: Gaza War

On 5 June 2014, Fatah signed a unity agreement with the Hamas political party.[128]

The 2014 Gaza War, also known as Operation Protective Edge, was a military operation launched by Israel on 8 July 2014 in the Gaza Strip. Following the kidnapping and murder of three Israeli teenagers in the West Bank by Hamas-affiliated Palestinian militants, the IDF initiated Operation Brother's Keeper, in which some 350 Palestinians, including nearly all of the active Hamas militants in the West Bank, were arrested.[129][130][131] Hamas subsequently fired a greater number of rockets into Israel from Gaza, triggering a seven-week-long conflict between the two sides. It was one of the deadliest outbreaks of open conflict between Israel and the Palestinians in decades. The combination of Palestinian rocket attacks and Israeli airstrikes resulted in thousands of deaths, the vast majority of which were Gazan Palestinians.[132]

2018–2019: Great March of Return

In 2018–2019, a series of protests, also known as the Great March of Return, were held each Friday in the Gaza Strip near the Israel–Gaza barrier from 30 March 2018 until 27 December 2019, during which a total of 223 Palestinians were killed by Israeli forces.[133][134] The demonstrators demanded that the Palestinian refugees must be allowed to return to lands they were displaced from in what is now Israel. They protested against Israel's land, air and sea blockade of the Gaza Strip and the United States recognition of Jerusalem as capital of Israel.[135][136][137]

Most of the demonstrators demonstrated peacefully far from the border fence. Peter Cammack, a fellow with the Middle East Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, argued that the march indicated a new trend in Palestinian society and Hamas, with a shift away from violence towards non-violent forms of protest.[138] Some demonstrators were setting tires on fire and launching Molotov cocktails and rocks toward the troops on the opposite side of the border.[139][140][141] Israeli officials said the demonstrations were used by Hamas as cover for launching attacks against Israel.[142]

In late February 2019, a United Nations Human Rights Council's independent commission found that of the 489 cases of Palestinian deaths or injuries analyzed, only two were possibly justified as responses to danger by Israeli security forces. The commission deemed the rest of the cases illegal, and concluded with a recommendation calling on Israel to examine whether war crimes or crimes against humanity had been committed, and if so, to bring those responsible to trial.[143][144]

On 28 February 2019, the Commission said it had "'reasonable grounds' to believe Israeli soldiers may have committed war crimes and shot at journalists, health workers and children during protests in Gaza in 2018." Israel refused to take part in the inquiry and rejected the report.[145]

2021: Israel–Palestine crisis

Before the 2021 Israel–Palestine crisis, Gaza had 48% unemployment and half of the population lived in poverty. During the crisis, 66 children died (551 children in the previous conflict). On 13 June 2021, a high level World Bank delegation visited Gaza to witness the damage. Mobilization with UN and EU partners is ongoing to finalize a needs assessment in support of Gaza's reconstruction and recovery.[146]

Another escalation between 5 and 8 August 2022 resulted in property damage and displacement of people as a result of airstrikes.[147][148]

2023–2024: Israel–Hamas war

On 7 October 2023, the paramilitaries in Gaza, led by the Hamas's Al-Qassam Brigades, invaded southwest Israel, targeting Israeli communities and military bases, killing at least 1,300 people and taking at least 236 hostages.[149] On 9 October 2023, Israel declared war on Hamas and imposed a "total blockade" of the Gaza Strip,[150] with Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant declaring, "There will be no electricity, no food, no fuel, everything is closed. We are fighting human animals and we are acting accordingly."[151][152] Gallant changed his position after pressure from US President Joe Biden, and a deal was made on 19 October for Israel and Egypt to allow aid into Gaza.[153] Gaza is currently undergoing a severe humanitarian crisis.[154] By 13 November 2023, one out of every 200 people in Gaza were killed, becoming one out of every 100 by January 2024.[155][156]

As of 29 October 2024[update], according to the Gaza Health Ministry, at least 43,000 Palestinians, including over 16,000 children, have been killed.[157] More than 85% of Palestinians in Gaza, or around 1.9 million people, were internally displaced.[158] As of January 2024, Israel's offensive has either damaged or destroyed 70–80% of all buildings in northern Gaza.[159][160]

After the outbreak of the Israel-Hamas war in 2023, there has been a renewed campaign to return Israeli settlers to Gush Katif,[161] including Hanan Ben Ari singing "We return to Gush Katif" to Israeli troops.[162]

Geography

The Gaza Strip is 41 km (25 mi) long, from 6 to 12 km (3.7 to 7.5 mi) wide, and has a total area of 365 km2 (141 sq mi).[27][9] It has a 51 km (32 mi) border with Israel, and an 11 km (7 mi) border with Egypt, near the city of Rafah.[163]

Khan Yunis is located 7 km (4.3 mi) northeast of Rafah, and several towns around Deir el-Balah are located along the coast between it and Gaza City. Beit Lahia and Beit Hanoun are located to the north and northeast of Gaza City, respectively. The Gush Katif bloc of Israeli settlements used to exist on the sand dunes adjacent to Rafah and Khan Yunis, along the southwestern edge of the 40 km (25 mi) Mediterranean coastline. Al Deira beach is a popular venue for surfers.[164]

The topography of the Gaza Strip is dominated by three ridges parallel to the coastline, which consist of Pleistocene-Holocene aged calcareous aeolian (wind deposited) sandstones, locally referred to as "kurkar", intercalated with red-coloured fine grained paleosols, referred to as "hamra". The three ridges are separated by wadis, which are filled with alluvial deposits.[165] The terrain is flat or rolling, with dunes near the coast. The highest point is Abu 'Awdah (Joz Abu 'Auda), at 105 m (344 ft) above sea level.

The major river in Gaza Strip is Wadi Gaza, around which the Wadi Gaza Nature Reserve was established, to protect the only coastal wetland in the Strip.[166][167]

Climate

The Gaza Strip has a hot semi-arid climate (Köppen BSh), with warm winters during which practically all the annual rainfall occurs, and dry, hot summers. Despite the dryness, humidity is high throughout the year. Annual rainfall is higher than in any part of Egypt at between 225 mm (9 in) in the south and 400 mm (16 in) in the north, but almost all of this falls between November and February.

Environment issues

Environmental problems in Gaza include desertification; salination of fresh water; sewage treatment; water-borne diseases; soil degradation; and depletion and contamination of underground water resources. A United Nations official said in 2024 that "it could take 14 years ... to clear debris, including rubble from destroyed buildings" (of the Israel–Hamas war).[168]

Governance

Hamas government

Since its takeover of Gaza, Hamas has exercised executive authority over the Gaza Strip, and it governs the territory through its own ad hoc executive, legislative, and judicial bodies.[169] The Hamas government of 2012 was the second Palestinian Hamas-dominated government, ruling over the Gaza Strip, since the split of the Palestinian National Authority in 2007. It was announced in early September 2012.[170] The reshuffle of the previous government was approved by Gaza-based Hamas MPs from the Palestinian Legislative Council or parliament.[170] Since the Hamas takeover in 2007, the Gaza Strip has been described as a "de facto one-party state", although it tolerates other political groups, including leftist ones such as the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) and the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine.[171][15]

The legal code Hamas applies in Gaza is based on Ottoman laws, the British Mandate's 1936 legal code, Palestinian Authority law, Sharia law, and Israeli military orders. Hamas maintains a judicial system with civilian and military courts and a public prosecution service.[169][172]

Gaza Strip was ranked 6th least electoral democracy in the Middle East and North Africa according to V-Dem Democracy indices in 2024 with a score of 0.136 out of one.[173]

Security

The Gaza Strip's security is mainly handled by Hamas through its military wing, the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades, internal security service, and civil police force. The Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades have an estimated 30,000 to 50,000 operatives.[174]

Other groups and ideologies

Other Palestinian militant factions operate in the Gaza Strip alongside, and sometimes opposed to Hamas. The Islamic Jihad Movement in Palestine, also known as the Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) is the second largest militant faction operating in the Gaza Strip. Its military wing, the Al-Quds Brigades, has an estimated 8,000 fighters.[175][176]

In June 2013, the Islamic Jihad broke ties with Hamas leaders after Hamas police fatally shot the commander of Islamic Jihad's military wing.[176] The third largest faction is the Popular Resistance Committees. Its military wing is known as the Al-Nasser Salah al-Deen Brigades.

Other factions include the Army of Islam (an Islamist faction of the Doghmush clan), the Nidal Al-Amoudi Battalion (an offshoot of the West Bank-based Fatah-linked al-Aqsa Martyrs' Brigades), the Abu Ali Mustapha Brigades (armed wing of the PFLP), the Sheikh Omar Hadid Brigade (ISIL offshoot), Humat al-Aqsa, Jaysh al-Ummah, Katibat al-Sheikh al-Emireen, the Mujahideen Brigades, and the Abdul al-Qadir al-Husseini Brigades.[177]

Some Salafi-Jihadis operating in Gaza have been using as part of their name the term ʻArḍ al-Ribat "Land of the Ribat", as a name for Palestine, literally meaning "the land of standing vigilant watch on the frontier", but understood in the context of global jihad, which is fundamentally opposed to local, Palestinian nationalism.[178]

Administrative divisions

The enclave is divided into five governorates: the North Gaza Governorate, Gaza Governorate, Deir al-Balah Governorate, Khan Yunis Governorate and Rafah Governorate.

Legality of Hamas rule

After Hamas's June 2007 takeover, it ousted Fatah-linked officials from positions of power and authority (such as government positions, security services, universities, newspapers, etc.) and strove to enforce law by progressively removing guns from the hands of peripheral militias, clans, and criminal groups, and gaining control of supply tunnels. According to Amnesty International, under Hamas rule, newspapers were closed down and journalists were harassed.[179] Fatah demonstrations were forbidden or suppressed, as in the case of a large demonstration on the anniversary of Yasser Arafat's death, which resulted in the deaths of seven people, after protesters hurled stones at Hamas security forces.[180]

Hamas and other militant groups continued to fire Qassam rockets across the border into Israel. According to Israel, between the Hamas takeover and the end of January 2008, 697 rockets and 822 mortar bombs were fired at Israeli towns.[181] In response, Israel targeted Qassam launchers and military targets and declared the Gaza Strip a hostile entity. In January 2008, Israel curtailed travel from Gaza, the entry of goods, and cut fuel supplies, resulting in power shortages. This brought charges that Israel was inflicting collective punishment on the Gaza population, leading to international condemnation. Despite multiple reports from within the Strip that food and other essentials were in short supply,[182] Israel said that Gaza had enough food and energy supplies for weeks.[183]

The Israeli government uses economic means to pressure Hamas. Among other things, it caused Israeli commercial enterprises like banks and fuel companies to stop doing business with the Gaza Strip. The role of private corporations in the relationship between Israel and the Gaza Strip is an issue that has not been extensively studied.[184]

Status

Due to both the Israeli blockade and Hamas's authoritarian policies and actions, US political organization Freedom House ranks Gaza as "not free".[169]

Israeli occupation

Despite the 2005 Israeli disengagement from Gaza,[20] the United Nations, international human rights organisations, and the majority of governments and legal commentators consider the territory to be still occupied by Israel, supported by additional restrictions placed on Gaza by Egypt.[185][186][187] Israel maintains direct external control over Gaza and indirect control over life within Gaza: it controls Gaza's air and maritime space, as well as six of Gaza's seven land crossings. It reserves the right to enter Gaza at will with its military and maintains a no-go buffer zone within the Gaza territory. Gaza is dependent on Israel for water, electricity, telecommunications, and other utilities.[20][188] The extensive Israeli buffer zone within the Strip renders much land off-limits to Gaza's inhabitants.[189] The system of control imposed by Israel was described in the fall 2012 edition of International Security as an "indirect occupation".[190] The European Union (EU) considers Gaza to be occupied.[191]

The international community regards all of the Palestinian territories including Gaza as occupied.[192] Human Rights Watch has declared at the UN Human Rights Council that it views Israel as a de facto occupying power in the Gaza Strip, even though Israel has no military or other presence, because the Oslo Accords authorize Israel to control the airspace and the territorial sea.[185][186][188]

In his statement on the 2008–2009 Israel–Gaza conflict, Richard Falk, United Nations Special Rapporteur wrote that international humanitarian law applied to Israel "in regard to the obligations of an Occupying Power and in the requirements of the laws of war."[193] Amnesty International, the World Health Organization, Oxfam, the International Committee of the Red Cross, the United Nations, the United Nations General Assembly, the UN Fact Finding Mission to Gaza, international human rights organizations, US government websites, the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office, and a significant number of legal commentators (Geoffrey Aronson, Meron Benvenisti, Claude Bruderlein, Sari Bashi, Kenneth Mann, Shane Darcy, John Reynolds, Yoram Dinstein, John Dugard, Marc S. Kaliser, Mustafa Mari, and Iain Scobbie) maintain that Israel's extensive direct external control over Gaza, and indirect control over the lives of its internal population mean that Gaza remained occupied.[194][195][196] In spite of Israel's withdrawal from Gaza in 2005, the Hamas government in Gaza considers Gaza as occupied territory.[197]

Israel states that it does not exercise effective control or authority over any land or institutions in the Gaza Strip and thus the Gaza Strip is no longer subject to the former military occupation.[198][199] Foreign Affairs Minister of Israel Tzipi Livni stated in January 2008: "Israel got out of Gaza. It dismantled its settlements there. No Israeli soldiers were left there after the disengagement."[200] On 30 January 2008, the Supreme Court of Israel ruled that the Gaza Strip was not occupied by Israel in a decision on a petition against Israeli restrictions against the Gaza Strip which argued that it remained occupied. The Supreme Court ruled that Israel has not exercised effective control over the Gaza Strip since 2005, and accordingly, it was no longer occupied.[201]

Some legal commentators agree with the Israeli position. In an analysis published in the Netherlands International Law Review, Hanne Cuyckens asserted that Gaza is no longer occupied, stating that there is no effective control under Article 42 of the Hague Regulations. While she acknowledged that Israel has obligations toward Gaza due to its level of control, she argued these responsibilities stem from general international humanitarian law and international human rights law, rather than the law of occupation.[202][202] Israeli law professors Yuval Shany and Avi Bell contested the classification of Gaza as occupied, with Shany asserting that it's difficult to view Israel as the occupying power under traditional law, while Bell argued that the Gaza Strip is not occupied as the blockade does not constitute effective control, citing international legal precedents requiring direct control over both the territory and its civilian population.[203][204] Likewise, Israeli Supreme Court judge Alex Stein argued in 2014 that Gaza was not occupied.[205] Michael W. Meier, a Visiting Professor at Emory University School of Law and Acting Director of Emory International Humanitarian Law Clinic, wrote that in his view, Gaza had not been occupied since 2005 as Israel no longer maintained military forces in the territory and because Hamas controlled most administrative functions and all public services, thus Israel did not have effective control.[206] Michael N. Schmitt likewise writes that Israel did not occupy Gaza after 2005, as in his view effective control requires some degree of power over daily governance of the territory, while Hamas often governed in manner contrary to Israeli interests and desires, and that if an area is regularly used as a base of significant military operations against another party to the conflict, the other party cannot be said to have effective control over it. However, he wrote that this did not mean Israel bore no obligations to the people of Gaza.[207]

On 19 July 2024, the International Court of Justice noted in Legal Consequences arising from the Policies and Practices of Israel in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem that "for the purpose of determining whether a territory remains occupied under international law, the decisive criterion is not whether the occupying Power retains its physical military presence in the territory at all times but rather whether its authority has been established and can be exercised" and concluded that "The sustained abuse by Israel of its position as an occupying Power, through annexation and an assertion of permanent control over the Occupied Palestinian Territory and continued frustration of the right of the Palestinian people to self-determination, violates fundamental principles of international law and renders Israel's presence in the Occupied Palestinian Territory unlawful". The court also ruled that Israel should pay full reparations to the Palestinian people for the damage the occupation has caused, and determined that its policies violate the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.[208]

Yuval Shany, along with law professors Amichai Cohen and Marko Milanović, argued that the court stopped short of declaring Gaza to be under occupation, but instead declared that Israel maintained certain obligations under the law of occupation. They noted the opinions of judges Yuji Iwasawa and Sarah Cleveland in particular. Judge Iwasawa pointed out that while the court stated Israel is bound by some obligations related to occupation law, it didn't determine whether Gaza remained "occupied" within the meaning of the law of occupation after 2005. Judge Cleveland noted that the court observed that after Israel's withdrawal in 2005, it continued to exercise key elements of authority over the Gaza Strip. This included "control of the land, sea and air borders, restrictions on movement of people and goods, collection of import and export taxes, and military control over the buffer zone." As a result, the court concluded that certain aspects of the law of occupation still applied to Gaza, based on Israel's level of effective control. However, it did not specify which obligations still bound Israel after 2005, nor did it find any violations of those obligations.[209][210]

Characterization as open-air prison

Several rights groups have characterized the situation in Gaza as an "open-air prison",[211][23] including the United Nations,[212] Human Rights Watch,[213] and the Norwegian Refugee Council.[214] This characterization was often cited by a number of human rights activists, politicians, and media news outlets reporting on the Gaza-Israel conflict and the wider Palestinian-Israeli conflict.[215][216] Former British Prime Minister David Cameron,[217] US Senator Bernie Sanders,[218] Israeli journalist Gideon Levy,[219] and Israeli historian Ilan Pappe have endorsed this characterization as well.[220]

In 2022, Human Rights Watch issued a report on the situation in the Gaza Strip, which it called an "open-air prison" due to the blockade and held Israel responsible as the occupying power, and to a lesser degree Egypt, which has restricted movement of Palestinians through its border.[213] The report highlighted how this blockade has led to humanitarian crises, namely shortages of essential supplies, limited access to healthcare, and high levels of poverty and unemployment among the Palestinian population in Gaza.[213] It claimed that Israel has formed a formal policy of separation between Gaza and the West Bank, despite both forming parts of the Palestinian territories.[213] The Israeli blockade on Gaza has restricted the freedom of movement of Gaza Palestinians to both the West Bank and the outside world; in particular, Palestinian professionals were most impacted by these restrictions, as applying for travel permit takes several weeks.[213]

The Norwegian Refugee Council report issued in 2018 called the territory "the world's largest open-air prison", highlighting in it several figures, including lack of access to clean water, to reliable electrical supply, to health care, food and employment opportunities.[214] It lamented the fact that a majority of Palestinian children in Gaza suffer from psychological trauma, and a portion of which suffer from stunted growth.[214]

Statehood

Some Israeli analysts have argued that the Gaza Strip can be considered a de facto state, even if not internationally recognized as such. Israeli Major General Giora Eiland, who headed Israel's National Security Council, has argued that after the disengagement and Hamas takeover, the Gaza Strip became a de facto state for all intents and purposes, writing that "It has clear borders, an effective government, an independent foreign policy and an army. These are the exact characteristics of a state."[221]

Yagil Levy, a professor of Political Sociology and Public Policy at the Open University of Israel, wrote in a Haaretz column that "Gaza is a state in every respect, at least as social scientists understand the term. It has a central government with an army that's subordinate to it and that protects a population living in a defined territory. Nevertheless, Gaza is a castrated state. Israel and Egypt control its borders. The Palestinian Authority pays for the salaries of some of its civil servants. And the army doesn't have a monopoly on armed force, because there are independent militias operating alongside it."[222]

Moshe Arens, a former Israeli diplomat who served as Foreign Minister and Defense Minister, likewise wrote that Gaza is a state as "it has a government, an army, a police force and courts that dispense justice of sorts."[223] In November 2018, Israeli Justice Minister Ayelet Shaked asserted that Gaza is an independent state, stating that Palestinians "already have a state" in Gaza.[224]

Geoffrey Aronson has likewise argued that the Gaza Strip can be considered a proto-state with some aspects of sovereignty, writing that "a proto-state already exists in the Gaza Strip, with objective attributes of sovereignty the Ramallah-based Mahmoud Abbas can only dream about. Gaza is a single, contiguous territory with de facto borders, recognised, if not always respected, by friend and foe alike. There are no permanently stationed foreign occupiers and, most importantly, no civilian Israeli settlements."[225] Writing in Newsweek, journalist Marc Schulman referred to Gaza as "an impoverished proto-state that lives off aid."[226]

Control over airspace

As agreed between Israel and the Palestinian Authority in the Oslo Accords, Israel has exclusive control over the airspace. Contrarily to the Oslo Accords, however, Israel interferes with Gaza's radio and TV transmissions, and Israel prevents the Palestinians from operating a seaport or airport.[86] The Accords permitted Palestinians to construct an airport, which was duly built and opened in 1998. Israel destroyed Gaza's only airport in 2001 and again in 2002, during the Second Intifada.[227][228]

The Israeli army makes use of drones, which can launch precise missiles. They are equipped with high-resolution cameras and other sensors. The missile fired from a drone has its own cameras that allow the operator to observe the target from the moment of firing. After a missile has been launched, the drone operator can remotely divert it elsewhere. Drone operators can view objects on the ground in detail during both day and night.[229] Israeli drones routinely patrol over Gaza, and engage in missile strikes which reportedly kill more civilians than militants; the drones also produce a buzzing noise audible from the ground which Palestinians in Gaza refer to as zanana.[230][231]: 6

Buffer zone

Part of the territory is depopulated because of the imposition of buffer zones on both the Israeli and Egyptian borders.[232][233][234]

Initially, Israel imposed a 50-meter buffer zone in Gaza.[235] In 2000, it was expanded to 150 meters.[233] Following the 2005 Israeli disengagement from Gaza, an undefined buffer zone was maintained, including a no-fishing zone along the coast. The ultimate effect of the enforcement of the no-fishing zone was that the fishing industry in Gaza "virtually ceased."[236]

In 2009/2010, Israel expanded the buffer zone to 300 meters.[237][235][238] The Israeli military stated that this buffer zone extended to 300 meters from the security fence, although UN bodies and other organizations operating in the region reported that the area extended at least a kilometer from the security fence before 2012. The buffer zone before the implementation of the ceasefire that followed the 2012 clashes accounted to 14% of the whole territory of the Strip and contained 30–55% of its total arable land. A 2012 UN report estimated that 75,000 metric tons of potential produce were lost per year as a result of the buffer zone, amounting to US$50.2 million per year.[239] The IDMC estimated in 2014 that 12% of the population of Gaza was directly affected by the land and sea restrictions due to the buffer zone.[240] [232][235]

On 25 February 2013, pursuant to a November 2012 ceasefire, Israel declared a buffer zone of 100 meters on land and 6 nautical miles offshore. In the following month, the zone was changed to 300 meters and 3 nautical miles. The 1994 Gaza Jericho Agreement allows 20 nautical miles, and the 2002 Bertini Commitment allows 12 nautical miles.[237][233]

In August 2015, the IDF confirmed a buffer zone of 300 meters for residents and 100 meters for farmers, but without explaining how to distinguish between the two.[241] As of 2015[update], on a third of Gaza's agricultural land, residents risk Israeli attacks. According to PCHR, Israeli attacks take place up to approximately 1.5 km (0.9 mi) from the border, making 17% of Gaza's total territory a risk zone.[233]

Israel says the buffer zone is needed to protect Israeli communities just over the border from sniper fire and rocket attacks. In the 18 months until November 2010, one Thai farm worker in Israel was killed by a rocket fired from Gaza. In 2010, according to IDF figures, 180 rockets and mortars had been fired into Israel by militants. In 6 months, 11 Palestinians civilians, including four children, had been killed by Israeli fire and at least 70 Palestinian civilians were injured in the same period, including at least 49 who were working collecting rubble and scrap metal.[232]

A buffer zone was also created on the Egyptian side of the Gaza–Egypt border. In 2014, scores of homes in Rafah were destroyed for the buffer zone.[242] According to Amnesty International, more than 800 homes were destroyed and more than 1,000 families evicted.[243] Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas agreed with the destruction of smuggling tunnels by flooding them, and then punishing the owners of the houses that contained entrances to the tunnels, including demolishing their houses, arguing that the tunnels had produced 1,800 millionaires, and were used for smuggling weapons, drugs, cash, and equipment for forging documents.[243]

Gaza blockade

Israel and Egypt maintain a blockade of the Gaza Strip in response to security concerns, such as the smuggling of weapons into Gaza. Israel has also stated that the blockade serves as "economic warfare".[33] The Israeli human rights organization Gisha reports that the blockade undermines basic living conditions and human rights in Gaza.[244] The Red Cross has reported that the blockade harms the economy and causes a shortage of basic medicines and equipment such as painkillers and x-ray film.[245]

Israel describes the blockade as necessary to prevent the smuggling of weapons into Gaza. Israel maintains that the blockade is legal and necessary to limit Palestinian rocket attacks from the Gaza Strip on its cities and to prevent Hamas from obtaining other weapons,[246][247][248] although the legality of the blockade has been challenged by multiple human rights organizations.[249][250]

According to director of the Shin Bet, Hamas and Islamic Jihad had smuggled in over "5,000 rockets with ranges up to 40 km (25 mi)." Some of the rockets could reach as far as the Tel Aviv Metropolitan Area.[251]

Facing mounting international pressure, Egypt lessened the restrictions starting in June 2010, when the Rafah border crossing from Egypt to Gaza was partially opened by Egypt. Egypt's foreign ministry said that the crossing would remain open mainly for people, but not for supplies.[252]

Israel also eased restrictions in June 2010 as a result of international pressure following the Gaza flotilla raid after which food shortages decreased.[253] The World Bank reported in 2012 that access to Gaza remained highly restricted and exports to the West Bank and Israel from Gaza are prohibited.[254] This ban on exports was not lifted until 2014.[255]

In January and February 2011, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) assessed measures taken to ease the blockade[256] and concluded that they were helpful but not sufficient to improve the lives of the local inhabitants.[256] UNOCHA called on Israel to reduce restrictions on exports and the import of construction materials, and to lift the general ban on movement between Gaza and the West Bank via Israel.[256] According to The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, the blockade resulted in a loss of over $17 million in exports in 2006 from 2005 (roughly 3% of all Palestinian exports).[257] After Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak resigned on 28 May 2011, Egypt permanently opened its border with Gaza to students, medical patients, and foreign passport holders.[256][258] Following the 2013 Egyptian coup d'état, Egypt's military has destroyed most of the 1,200 tunnels which are used for smuggling food, weapons, and other goods to Gaza.[259] After the August 2013 Rabaa Massacre in Egypt, the border crossing was closed 'indefinitely.'[260]

While the import of food is restricted through the Gaza blockade, the Israeli military destroys agricultural crops by spraying toxic chemicals over the Gazan lands, using aircraft flying over the border zone. According to the IDF, the spraying is intended "to prevent the concealment of IED's [Improvised Explosive Devices], and to disrupt and prevent the use of the area for destructive purposes."[261] Gaza's agricultural research and development station was destroyed in 2014 and again in January 2016, while import of new equipment is obstructed.[262]

Movement of people

Because of the Israeli–Egyptian blockade, the population is not free to leave or enter the Gaza Strip. Only in exceptional cases are people allowed to pass through the Erez Crossing or the Rafah Border Crossing.[237][263] In 2015, a Gazan woman was not allowed to travel through Israel to Jordan on her way to her own wedding. The Israeli authorities found she did not meet the criteria for travel, namely only in exceptional humanitarian cases.[264]

Under the long-term blockade, the Gaza Strip is often described as a "prison-camp or open air prison for its collective denizens". The comparison is done by observers, ranging from Roger Cohen and Lawrence Weschler to NGOs, such as B'tselem, and politicians and diplomats, such as David Cameron, Noam Chomsky, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, David Shoebridge and Sir John Holmes.[265] In 2014 French President François Hollande called for the demilitarization of Gaza and a lifting of the blockade, saying "Gaza must neither be an open prison nor a military base."[266]

An anonymous Israeli analyst has called it "Israel's Alcatraz".[267] While Lauren Booth,[268][269] Philip Slater,[270] Giorgio Agamben[271] compare it to a concentration camp. For Robert S. Wistrich,[272] and Philip Mendes,[273] such analogies are designed to offend Jews, while Philip Seib dismisses the comparison as absurd, and claims that it arises from sources like Al Jazeera and Arab leaders.[274]

Israel restricts movement of Palestinian residents between the West Bank and Gaza. Israel has implemented a policy of allowing Palestinian movement from the West Bank to Gaza, but making it quite difficult for Gaza residents to move to the West Bank. Israel typically refuses to allow Gaza residents to leave for the West Bank, even when the Gaza resident is originally a West Bank resident. The Israeli human-rights organization Gisha has helped Gaza residents who had moved from the West Bank to Gaza return to the West Bank arguing that extremely pressing personal circumstances provide humanitarian grounds for relief.[275]

Economy

During the course of the Israeli occupation, Gaza's economy has gone from a state of under-development with a deep dependency on Israel and strong ties to the West Bank, to a now isolated economy, deprived of the capacity to produce and innovate and subject to the damage of ongoing Israeli military attacks. Gaza's economy is characterized by high levels of unemployment and impoverishment, with over 75% of the population dependent on humanitarian aid. Political economist Sara Roy, the leading authority on the economy of the Gaza Strip, describes the 2005 Israeli disengagement from Gaza as a turning point in Israeli policy, where previously Israel sought to control and dominate the economy of the Strip to serve its own interests, current policies seek to disable the economy, with the political goal of reducing the demands of the population for national, political and economic rights into a humanitarian problem.[33]

The economy of the Gaza Strip is severely hampered by Egypt and Israel's almost total blockade, and has one of the world's highest population densities,[28][29] limited land access, strict internal and external security controls, the effects of Israeli military operations, and restrictions on labor and trade access across the border. A 2015 UN report estimated that 72% of the population suffers from food insecurity.[276] Per capita income was estimated at US$3,100 in 2009, a position of 164th in the world.[9] A UN report in 2022 estimated Gaza Strip's unemployment rate to be 45% and 65% of the population under poverty, living standards went down by 27% compared to 2006 and 80% of the population depends on international aid for survival.[277]

Access to essential needs, such as water, is limited, with only 10–25% of households having access to running water on a daily basis, typically for only a few hours a day. Out of "dire necessity", 75–90% of the population relies on unsafe water from unregulated vendors. Accordingly, 26% of disease in Gaza is water related and a 48% prevalence of nitrate poisoning in children. The water shortage in Gaza is a result of Israeli policies and control of aquifers, withholding from Gaza enough water to meet Gaza's needs many times over.[33]

The EU described the Gaza economy in 2013 as follows: "Since Hamas took control of Gaza in 2007 and following the closure imposed by Israel, the situation in the Strip has been one of chronic need, de-development and donor dependency, despite a temporary relaxation on restrictions in movement of people and goods following a flotilla raid in 2010. The closure has effectively cut off access for exports to traditional markets in Israel, transfers to the West Bank and has severely restricted imports. Exports are now down to 2% of 2007 levels."[191]

According to Sara Roy, one senior IDF officer told an UNWRA official in 2015 that Israel's policy towards Gaza consisted of: "No development, no prosperity, no humanitarian crisis."[278]

Israeli policies following Israeli military occupation

In 1984, former deputy mayor of Jerusalem, Meron Benvenisti, described Israeli policy in the occupied territories as motivated primarily by the notion that Palestinian claims to economic and political rights are illegitimate. He wrote that the economic policies stifle Palestinian economic development with the primary goal of prohibiting the establishment of a Palestinian state.[279]

Sara Roy describes Israeli policies in Gaza as policies of "de-development," which are specifically designed to destroy an economy and ensure that there can be no economic base to support local, independent development and growth. Roy explains that the framework for Israeli policy established between 1967 and 1973 would not change, even with the limited self-rule introduced by the Oslo Accords in the 1990s, but would grow dramatically more draconian in the early 2000s.[280]

Israeli economic policies in Gaza tied long-term development directly to conditions and interests in Israel rather than to productive domestic structural reform and development. With reduced access to its own resources (largely deprived of them as a result of Israel policies[281]), Gaza's economy grew increasingly dependent on external sources of income. Israeli policies under the authority of the military government exacerbated dependence while externalizing (or reorienting) the economy towards Israeli priorities. This reorientation of the economy included shifting the labor force away from developing domestic agriculture and industry towards labor-intensive subcontracting jobs supporting Israeli industry in addition to unskilled labor jobs in Israel itself. Notably, the Israeli government barred Palestinians of Gaza from taking white-collar roles in public services (with the exception of services such as street cleaning).[282][283] In 1992, 70% of Gaza's labor force worked in Israel, 90% of Gaza's imports came through Israel, and 80% of its exports went through Israel.[284]

Israeli efforts to expand employment within Gaza were largely through relief works, which, as a purely income-generating project, does not contribute to development.[285] The Israeli military government's expenditure on industry in the Gaza Strip between 1984 and 1986 was 0.3% of the total budget, with the development of industry receiving no investment at all.[286][287] Despite the worsening living conditions in Gaza, the Israeli government continued to invest minimally throughout the military government's rule. The Gaza budget did not impose any financial burden on Israeli taxpayers, despite statements from Israeli officials that limited investment was due to financial constraints. From the 1970s and throughout the duration of the Israeli military government's authority, income tax deductions from Palestinians in Gaza exceeded Israeli expenditure, resulting in a net transfer of money from Gaza into Israel.[288] Throughout its authority, the Israeli military government maintained a budget with little to no capital investment in Gaza. Additionally, the fiscal system resulted in a net outflow of domestic resources from the Palestinian economy.[284]

The result was the continuous transfer of local resources out of Gaza's economy and the increased vulnerability of the economy to external conditions such as Israeli market needs, but most vividly seen by the impacts of the current Israeli blockade and Israel's destructive military campaigns in Gaza. The economy's extreme dependence on Israel during this period is highlighted by the fact that by 1987, 60% of Gaza's GNP came from external payments, primarily through employment in Israel. Israeli policies also undercut any potential competition from Gazan products through generous subsidies to Israeli agriculture. Further, Israel banned exports to all Western markets, and enterprises that might compete with Israeli counterparts suffered as a result of the military authority's regulation. For example, permits from military authorities (which could take five years or longer to acquire) were required in order to plant new citrus trees or replace old ones, and farmers were prohibited from clearing their own land without permission. In addition, military authorities constrained fishing areas to prevent any threat of competition with Israeli products. Even juice and vegetable processing factories (which could make productive use of crop surpluses) were prohibited by the Israeli government until 1992.[289] As Sara Roy describes, Gazan "[e]conomic activity is determined by state policies, not market dynamics."[290]

Policies of the Israeli military authorities in Gaza also restricted and undermined institutions that could support and plan for productive investment and economic development. Permission was required, for example, for the development of any new programs and for personnel change. Permission was also required to hold a meeting of three or more people. From the start of the occupation until 1994, municipalities did not have authority over, for example, water and electricity allocation, public markets, public health, and transportation. Decision-making and the initiation of new projects required the approval of the military governor. Even under the Oslo agreement, Israel maintains authority over zoning and land use. Further, municipal governments had no authority to generate revenue. Specifically, they could not introduce taxes or fees without approval from Israeli authorities. Accordingly, municipalities and local institutions often relied on donations from external sources, although access to the funds was often denied even after they had been deposited in Israeli banks. At the start of the occupation, the military government closed all Arab banks in the occupied territories. Branches of Israeli banks were allowed to transfer funds and provide services for importing and exporting businesses. Further, no banks were allowed to supply long-term credit, which seriously limited the potential for economic development.[291]

Industries

Gaza Strip industries are generally small family businesses that produce textiles, soap, olive-wood carvings, and mother-of-pearl souvenirs. The main agricultural products are olives, citrus, vegetables, Halal beef, and dairy products. Primary exports are citrus and cut flowers, while primary imports are food, consumer goods, and construction materials. The main trade partners of the Gaza Strip are Israel and Egypt.[9]

Natural resources

Natural resources of Gaza include arable land—about a third of the Strip is irrigated. Recently, natural gas was discovered. The Gaza Strip is largely dependent on water from Wadi Gaza, which also supplies Israel.[292] Most of water comes from groundwater wells (90% in 2021). Its quality is low and most of it is unfit for human consumption. The remainder is produced by water desalination plants or bought from Israel's Mekorot (6% of all water in 2021).[293] According to Human Rights Watch, international humanitarian law requires Israel, as the occupying power in Gaza, to ensure that the basic needs of the civilian population are provided for.[294]

Gaza's marine gas reserves extend 32 kilometres from the Gaza Strip's coastline[295] and were calculated at 35 BCM.[296]

Society

Demographics

In 2010, approximately 1.6 million people lived in the Gaza Strip,[9] almost 1.0 million of them were UN-registered refugees.[297] The majority descend from refugees who were driven from or left their homes during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. The Strip's population has continued to increase since that time, mainly due to a total fertility rate which peaked at 8.3 children per woman in 1991. This fell to 4.4 children per woman in 2013 which was still among the highest worldwide.[9][298]

In a ranking by total fertility rate, this places Gaza 34th of 224 regions.[9][298] This leads to the Gaza Strip having an unusually high proportion of children in the population, with 43.5% of the population being 14 or younger and a median age in 2014 of 18, compared to a world average of 28, and 30 in Israel. The only countries with a lower median age are countries in Africa such as Uganda where it was 15.[298]

Religion

Sunni Muslims make up 99.8 percent of the population in the Gaza Strip, with an estimated 2,000 to 3,000 (0.2 percent) Arab Christians.[299][9]

From 1987 to 1991, during the First Intifada, Hamas campaigned for the wearing of the hijab head-cover. In the course of this campaign, women who chose not to wear the hijab were verbally and physically harassed by Hamas activists, leading to hijabs being worn "just to avoid problems on the streets".[300]

Since Hamas took over in 2007, attempts have been made by Islamist activists to impose "Islamic dress" and to require women to wear the hijab.[301][302] The government's "Islamic Endowment Ministry" has deployed Virtue Committee members to warn citizens of the "dangers of immodest dress, card playing and dating".[303] However, there are no government laws imposing dress and other moral standards, and the Hamas education ministry reversed one effort to impose Islamic dress on students.[301] There has also been successful resistance[by whom?] to attempts by local Hamas officials to impose Islamic dress on women.[304]

According to Human Rights Watch, the Hamas-controlled government stepped up its efforts to "Islamize" Gaza in 2010, efforts it says included the "repression of civil society" and "severe violations of personal freedom."[305]

Palestinian researcher Khaled Al-Hroub has criticized what he called the "Taliban-like steps" Hamas has taken: "The Islamization that has been forced upon the Gaza Strip—the suppression of social, cultural, and press freedoms that do not suit Hamas's view[s]—is an egregious deed that must be opposed. It is the reenactment, under a religious guise, of the experience of [other] totalitarian regimes and dictatorships."[306] Hamas officials denied having any plans to impose Islamic law. One legislator stated that "[w]hat you are seeing are incidents, not policy" and that "we believe in persuasion".[303]

Violence against Christians has been recorded. The owner of a Christian bookshop was abducted and murdered[307] and in February 2008, the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) library in Gaza City was bombed.[308] At least eighteen people were killed when Israel bombed the Church of Saint Porphyrius, which is the oldest in Gaza, on 19 October 2023.[309]

In addition to Hamas, a Salafist movement began to appear about 2005 in Gaza, characterized by "a strict lifestyle based on that of the earliest followers of Islam".[310] As of 2015[update], there are estimated to be only "hundreds or perhaps a few thousand" Salafists in Gaza.[310]

Education

Palestine had a reported 97% literacy rate (96% for females, 99% for males) in 2019 and youth literacy rate (ages 15–24) of 88% in 2020 (94% for females, 82% for males).[32] According to UNRWA figures, there are 640 schools in Gaza: 383 government schools, 221 UNRWA schools and 36 private schools, serving a total of 441,452 students.[311]

In 2010, Al Zahara, a private school in central Gaza introduced a special program for mental development based on math computations. The program was created in Malaysia in 1993, according to the school principal, Majed al-Bari.[312]

In June 2011, some Gazans, upset that UNRWA did not rebuild their homes that were lost in the Second Intifada, blocked UNRWA from performing its services and shut down UNRWA's summer camps. Gaza residents closed UNRWA's emergency department, social services office and ration stores.[313]

In 2012, there were five universities in the Gaza Strip and eight new schools were under construction.[314] By 2018, nine universities were open.

The Community College of Applied Science and Technology (CCAST) was established in 1998 in Gaza City. In 2003, the college moved into its new campus and established the Gaza Polytechnic Institute (GPI) in 2006 in southern Gaza. In 2007, the college received accreditation to award BA degrees as the University College of Applied Sciences (UCAS). In 2010, the college had a student population of 6,000, in eight departments offering over 40 majors.[315]

Health

In Gaza, there are hospitals and additional healthcare facilities. Because of the high number of young people the mortality rate is one of the lowest in the world, at 0.315% per year.[316] The infant mortality rate is ranked 105th highest out of 224 countries and territories, at 16.55 deaths per 1,000 births.[317] The Gaza Strip places 24th out of 135 countries according to Human Poverty Index. According to the World Health Organization, in 2022 the average life expectancy for males was 72.5 years and 75 years for females, about the same as Egypt, Lebanon or Jordan, but lower than in Israel.[318]

A study carried out by Johns Hopkins University (US) and Al-Quds University (in Abu Dis) for CARE International in late 2002 revealed very high levels of dietary deficiency among the Palestinian population. The study found that 17.5% of children aged 6–59 months suffered from chronic malnutrition. 53% of women of reproductive age and 44% of children were found to be anemic. Insecurity in obtaining sufficient food as of 2016 affects roughly 70% of Gaza households, as the number of people requiring assistance from UN agencies has risen from 72,000 in 2000, to 800,000 in 2014.[319]

After the Hamas takeover of the Gaza Strip health conditions in Gaza Strip faced new challenges. World Health Organization (WHO) expressed its concerns about the consequences of the Palestinian internal political fragmentation; the socioeconomic decline; military actions; and the physical, psychological and economic isolation on the health of the population in Gaza.[320] In a 2012 study of the occupied territories, the WHO reported that roughly 50% of the young children and infants under two years old and 39.1% of pregnant women receiving antenatal services care in Gaza suffer from iron-deficiency anemia. The organization also observed chronic malnutrition in children under five "is not improving and may be deteriorating."[321]

According to Palestinian leaders in the Gaza Strip, the majority of medical aid delivered are "past their expiration date." Mounir el-Barash, the director of donations in Gaza's health department, claims 30% of aid sent to Gaza is used.[322][failed verification]

Gazans who desire medical care in Israeli hospitals must apply for a medical visa permit. In 2007, State of Israel granted 7,176 permits and denied 1,627.[323][324]

In 2012, two hospitals funded by Turkey and Saudi Arabia were under construction.[325]

As a result of fighting in Gaza during the Israel-Hamas war, many of Gaza's hospitals have sustained serious damage.[326]

Culture and sports

Fine arts

The Gaza Strip has been home to a significant branch of the contemporary Palestinian art movement since the mid-20th century. Notable artists include painters Ismail Ashour, Shafiq Redwan, Bashir Senwar, Majed Shalla, Fayez Sersawi, Abdul Rahman al Muzayan and Ismail Shammout, and media artists Taysir Batniji (who lives in France) and Laila al Shawa (who lives in London). An emerging generation of artists is also active in nonprofit art organizations such as Windows From Gaza and Eltiqa Group, which regularly host exhibitions and events open to the public.[327]

Hikaye